From segregation to free primary, the lessons have been difficult for Kenya

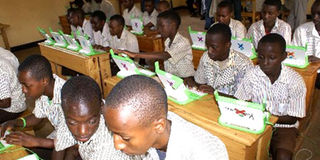

Primary school pupils use laptops during a lesson. Photo/FILE

What you need to know:

- Arising out of the Mackay Report, Moi University was set up in 1984 as the second university and with the mandate of offering technology-related courses. Soon after in 1985, Kenyatta University College, which had been a constituent college of the University of Nairobi, was upgraded to raise the number of universities to three.

- In its twilight years, the Kibaki administration expanded university education, with the number of public universities rising from seven to 22, with nine constituent colleges and three campuses in 2013. Fully chartered private universities also increased from six in 2002 to 17 in 2013, plus 19 others are in various stages of accreditation to offer their own degrees.

At independence, Kenya’s new government committed itself to tackling three challenges, namely poverty, disease and ignorance.

This was based on the understanding that the nation’s social progress and economic prosperity were predicated on wealth creation, good health and knowledge acquired through relevant education.

The Kanu Manifesto of 1963 on which the party scored electoral victory at the first General Election made ambitious proposals on education, including providing free universal basic education.

Education was a critical plank in the transformation of a new Kenya. But the kind of education inherited from the colonial administration was not going to help in realising that goal. First, the system was discriminatory and created a segregated society based on race. The best education was reserved for the children of the Whites and Asians.

At the end of the spectrum were Africans, who were left to contend with inferior education ostensibly to ensure that they did not gain the knowledge and skills to challenge British supremacy.

Thus the first step undertaken by the Kenyatta administration to set up a commission under Prof Simeon Ominde in 1964, with the brief to assess the existing education system and provide policy to move in a new direction on education.

The team’s findings were published in the Report of the Kenya Education Commission, popularly known as the Ominde Report. Notable among its key highlights were: creating a unitary education system to eliminate the disparities inherited at independence; providing free primary education; having a common system for recruiting and paying teachers; and promoting secondary and higher education to provide human resource to drive the economy.

The Sessional Paper No 10 of 1965 on African Socialism and its Application to Planning in Kenya, which provided the country’s development blueprint, reinforced these.

Significantly, the Ominde commission established a new education system comprising seven years of primary education, four in secondary, two in high school and three at the university (7-4-2-3). It also abolished the then Kenya Preliminary Examinations (KPE) done at Standard Four and Higher School Certificate that was done at the end of secondary education.

Instead, it introduced a new examination at Standard Seven (Certificate of Primary Education), another at Form Two, known as Kenya Junior Secondary Education, and General School Certificate at Form Four and at Form Six.

After the first decade of independence, it became apparent that the education model, though it expanded enrolment figures, was inadequate to push the country to the economic and technological levels it desired. The oil shocks of the early 1970s and the subsequent economic stagnation, which depressed the job market, compelled the government to re-examine whether the educational objectives matched the economic goals.

So in 1976 the government set up another committee to review the education system.

However, the recommendations of the Report of The National Committee on Educational Objectives and Policies, also known as Gachathi Report, were never implemented. With the benefit of hindsight, this was the period of intense political rivalry in the sunset years of President Jomo Kenyatta and the political focus was on succession rather than on pursuing a broader developmental agenda.

A major turning point, however, came in 1981 following the publication of the Report of the Presidential Party on Second University in Kenya under the chairmanship of a Canadian, Prof Collins Mackay, which recommended a complete change of the education system.

Paradoxically, its mandate was to make proposals on setting up a second university to complement the University of Nairobi and its constituent, Kenyatta University College. But the Mackay team went ahead to make recommendations that radically changed the education system by introducing 8-4-4 to replace Ominde’s 7-4-2-3.

Specifically, Forms Five and Six (A Level) were scrapped; primary education extended to eight years and university education to four years. The 8-4-4 education system was implemented in 1985 and has continued to date.

Arising out of the Mackay Report, Moi University was set up in 1984 as the second university and with the mandate of offering technology-related courses. Soon after in 1985, Kenyatta University College, which had been a constituent college of the University of Nairobi, was upgraded to raise the number of universities to three.

Between 1980 and 2000, the education sector recorded mixed results. In one respect, the number of universities grew to seven, while that of middle level colleges declined.

The Mwai Kibaki era from 2003 saw the rejuvenation of education. Ascending to power on a popular wave under Narc, the administration introduced free primary education in 2003 and followed it with subsidised secondary education in 2008, which collectively raised enrolments at all levels.

In its twilight years, the Kibaki administration expanded university education, with the number of public universities rising from seven to 22, with nine constituent colleges and three campuses in 2013. Fully chartered private universities also increased from six in 2002 to 17 in 2013, plus 19 others are in various stages of accreditation to offer their own degrees.

Cumulatively, education has undergone massive expansion in the past 50 years. While at independence, there were only 891,553 children enrolled in primary schools, the number has grown nearly 10 times to the current 9.9 million. Similarly, enrolments rose remarkably in secondary schools, from 30,120 in 1963 to 1.9 million in 2013.

Whereas Kenya had no single university at independence, today, there are 22 public universities, as well as 12 constituent colleges and three campuses.

In addition, there are 17 fully-fledged private universities plus 19 others at different stages of accreditation. Collectively, the universities have an enrolment of 250,000 students, compared to 290 in 1963 when there was only the University of East Africa with campuses at Makarere, Nairobi and Dar es Salaam.

During the period, the main challenges in education have been quality of learning, relevance of curriculum, inadequate funding, perennial teacher shortage, and unemployment of the youth leaving schools and colleges. Thus, it is incumbent on the leadership to give special attention to these issues to revamp education and prepare the youth for the challenges of the next half century.

Mr Aduda, an editor at Nation, is a specialist in education