The radical world of the MRC

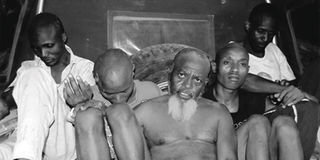

MRC founder member and secretary-general Randu Nzai Ruwa (centre) in the Shanzu Law Courts, Mombasa, where he was charged with incitement to violence and disobedience of the law. The charges stated that he was found with a white T-shirt with the words ‘Pwani si Kenya, MRC, Nchi Mpya Maisha Mapya’. Photo/GIDEON MAUNDU

What you need to know:

- Unlike earlier Mombasa groups that were set up to intimidate the opposition during the days of Kanu, MRC is bent on detaching the region from Kenya and all signs are that it means business

The Mombasa Republican Council has been agitating for the secession of Coast region for the past two or three years.

It was not associated with violence until the attack on Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) officials conducting a mock election in Malindi. The message was that the group would not allow elections in Coast Province because it considers the region a separate entity from the Republic of Kenya.

A fortnight ago, Fisheries Minister Amason Kingi was attacked at Mtwapa, Kilifi County. Four people, including the minister’s bodyguard, were killed. Retired Industrial Court judge Steward Madzayo, who wants to contest the senator’s seat in Kilifi County, was injured during the incident.

Internal Security Minister Katoo ole Metito says the government will “deal firmly” with such groups. Mr Francis Kimemia, the acting head of the civil service, has issued a similar warning.

Last week, seven leaders of the secessionist group were arrested and charged before a Mombasa court with incitement to violence.

Among them were MRC spokesman Mohamed Mraja and branch officials Ali Mbwana Mwatete and Ali Juma. The others were Mr Oma Gwashe of Kilifi, Mr Hassan Mbwana Mwanguza, Mr Ali Hassan Ngome, and Mr Said Jadi Mwachaunga, all of Kwale.

Mr Mbwana and Mr Juma separately denied the incitement charge.

Three High Court judges ruled in July that the Kenya Gazette notice that outlawed the MRC was unconstitutional. Judges John Mwera, Mary Kasango, and Francis Tuiyott said the State had failed to demonstrate that the ban was justifiable and proportionate.

In August, Attorney-General Githu Muigai appealed against the ruling. The orders were sought on grounds that soon after the court decision, members of the Mombasa Republican Council engaged in criminal activity by releasing leaflets in public places and making alarming statements in the electronic and print media inimical to peace and security in the Coast region.

According to the application, one of the MRC statements is to the effect that the secessionists would not register as a political party, as recommended by the court. Another statement was that the 2013 elections would not be allowed to take place in the Coast Province.

On Tuesday, Internal Security and Provincial Administration assistant minister Alfred Khangati told Parliament that the government had identified the financiers of MRC and was watching them.

Mr Khangati said the government had noted that suspected MRC adherents were always bailed out by certain wealthy people when they were arrested.

Other reports indicate that foreign forces could be involved in bankrolling MRC activities.

MRC is not the first proscribed group to cause a storm at the Coast. The trend can be traced to the agitation for multi-partyism in the 1990s when the unregistered Islamic Party of Kenya (IPK), led by controversial Muslim preacher Sheikh Khalid Balala, was formed. Several groups were set up to counter IPK, which supported multi-partyism.

To counter the challenge against then President Daniel Moi’s government, Kanu leaders from different parts of the country launched a series of rallies to agitate for a majimbo system of government as a strategy to counter opposition leaders’ call for multi-partyism.

At the Coast, the majimbo rallies were led by then Kanu politician Shariff Nassir and political activist Emmanuel Maitha.

Majimboism or federalism is an emotive issue at the Coast. Calls for this system of government were started by Coast political kingpin Ronald Ngala of the Kenya African Democratic Union (Kadu) before independence.

The Coast enjoyed a brief era of regional autonomy before the Kenyatta administration brought regional governments to their knees by simply denying them money.

Mr Ngala, according Mr Duncan Ndegwa’s Walking in Kenyatta Struggles, had declared himself the president of the coastal region and occupied what is now State House, Mombasa. He partitioned it using cardboard and fixed a flag on his car, which the young Cabinet minister Tom Mboya never tired of removing.

According to the report of the Kennedy Kiliku-chaired Parliamentary Select Committee to investigate ethnic clashes in the country in 1992, the Moi-era majimbo rallies were to blame for the violence that erupted in different parts of the country ahead of the General Election that year.

The report says some of the majimbo architects said they had drafted a constitution which would result in “outsiders” in some parts of the country being required to go back to their “motherland”.

Leaflets threatening up-country people with eviction from the Coast region emerged in different parts of Mombasa. Before investigations could establish what was going on, a group of youths raided quarries in Likoni and Kwale and attacked miners, who were mostly from Nyanza.

MRC pegs its secessionist drive on what it terms historical injustices that revolve around land and unfair distribution of national resources.

Top government officials, including representatives from the National Security Intelligence Service, have met the group’s officials in an effort to understand their grievances.

MRC is just one of several quasi-political or proscribed groups at the Coast. Others include IPK, Kaya Bombo, Mulungunipa, Coast Protective Group (CPG), and United Muslims of Africa (UMA).

UMA was led by political activist Omar Masumbuko while CPG was led by former Kisauni MP Emmanuel Karisa Maitha, who died in 2004. The secretary-general of the group was Nyonga wa Makemba.

Mr Masumbuko and Mr Makemba confirmed said UMA and CPG were formed to counter IPK and fight for Coast people’s rights.

“We formed UMA to fight IPK because it (IPK) was not following Muslim teachings and it was politicising Islam,” he said.

Mr Masumbuko says he regrets starting UMA.

“I started UMA for a noble cause, but I got into trouble, resulting in my being linked to the 1997 violence.” He said he was arrested and charged in court, but was later acquitted. Mr Makemba says the same fate was to befall most CPG members.

“Most of our members were rounded up and charged in connection with the 1997 violence at the Coast although we were not involved,” he said. Both Mr Makemba and Mr Masumbuko deny any links to MRC.

However, they admit recruiting youths for UMA and CPG and training them to counter the IPK.

The youths were trained at the Mama Ngina Drive, near Kilindini Channel. Shortly afterwards, under the protection of armed security personnel, they attacked IPK strongholds in Kibokoni and Old Town, leaving a trail of destruction.

Hundreds of vehicles were burnt and homes looted, several youths maimed and others killed, while women were raped. Soon afterwards, IPK disintegrated and UMA and CPG fizzled out.

No action was taken against UMA and CPG, but IPK officials, including Sheikh Balala, were arrested and charged.

According to the report by the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Tribal Clashes in Kenya that was chaired by Mr Justice A.M. Akiwumi, Mr Maitha confessed to having been tasked, together with Mr Masumbuko, with training Muslim youths from Kwale and parts of Mombasa to silence IPK in Mombasa.

He said he used youths associated with UMA and CPG to fight IPK and attack and disrupt the rallies of opposition parties.

The commission reported that Mr Maitha had confessed in statement, which he later denied, that his actions were supported by government officials such as the area district commissioner, the provincial police officer, and the provincial criminal investigations officer.

“Both the district and provincial security committees, which he said sanctioned his actions and indeed provided necessary funds, would often call on him for information that they may require,” the Akiwumi Commission report says.

Just before the 1997 General Election, leaflets threatening up-country people with eviction emerged again, this time round by a group calling itself Kaya Bombo.

Reports of youths being recruited, taking oaths, and undergoing military training in forests and caves in Kwale and Kilifi counties were widespread.

Subsequent investigations led to the arrest of several youths in Kwale and Kilifi counties. They were charged with oathing and undergoing illegal military training. They were bonded to keep the peace.

Then on the night of August 13, 1997, raiders attacked the Likoni police station, stole 43 guns and 1,400 rounds of ammunition before engaging in an orgy of violence that left more than 10 people dead, many others homeless, and property worth millions of shillings destroyed.

Several people including Mr Masumbuko and a witchdoctor who allegedly administered oaths to the youths, Mzee Swaleh Alfan, were arrested and charged. However, they were released due to lack of evidence.

The 1997 Likoni clashes had a devastating effect on tourism and the economy in general.

The South Coast was the hardest hit and several hotels were closed, resulting in the loss of hundreds of jobs. It was not until 2001 that tourism started to recover.

According to the findings of the Kiliku and Akiwumi commissions of inquiry into ethic violence, the ragtag groups can be traced to politicians.

The Akiwumi Commission recommended that several government officials who served at the Coast at the time of the violence and politicians from the region be investigated.

A number of the Coast elite and politicians have been associated with the MRC. Reports indicate that a number of Coast MPs privately say they support the group.

The profiles of the people claiming the leadership of MRC indicates that they do not have the capacity and political persuasion to lead an organisation of such magnitude.

This reinforces suspicions that the real ideologues and brains behind MRC are lurking in the shadows.