Why there are few Ngugi, Achebe successors

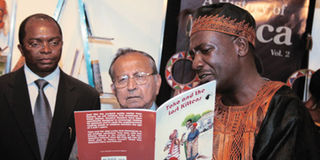

PHOTO | FILE Author Yusuf Dawood (C) samples one of the new books at a past Book Fair in Nairobi.

What you need to know:

- Nine out 10 undergraduates do not know a young writer from their generation because their conception of literature is the rigid, pedantic and didactic form in which it is taught

Beyond the aesthetics and the enlightenment role literature also chronicles historical events, especially conflicts.

Rather curiously, since the Biafra war in Nigeria 40-odd years ago, African literature has often steered clear of the wars and turmoil that the continent has witnessed.

So much that the latest magnum opus accepted both in academic and social circles is Chimamanda Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun which, for all its deserved acclaim, had to rely on the Biafran war!

Genocidal

Post-colonial Africa has seen some of the worst conflicts to ever visit humankind. Liberia, Sierra Leone, D RCongo, Angola, Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti, Rwanda and Burundi have all had civil wars, some genocidal.

From these countries the only known thing close to literature is the movie and documentary Blood Diamond from Hollywood.

One or two Western African countries have experienced coups in last five years.

For DR Congo, it seems they will settle once all minerals have been depleted.

Of course a dozen self-appraising biographies by those who survive the horrendous conflicts (no disrespect to them whatsoever) are on display in all leading bookstores across European capitals. They have gone ahead to milk the conflict through the sales and the NGOs they set up to help various humanitarian causes in their respective countries.

Often for the better, often for nothing (when they don’t pick up)... often for worse, especially when the money flows.

However, when it comes to a book of canonical proportions, literary speaking, none has been forthcoming.

It is so bad that even lecturers and tutors in colleges and universities, in a bid to “modernise” African literature, switched from Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Chinua Achebe straight to Adichie, who took us back to Biafra (2007, forty years later.)

The illusion is that we do not have writers who can match the authority of the septuagenarians and octogenarians who have dominated the literary space for five decades. Maybe.

Memorable book

Colonialism gave birth to them. Corruption and the successive civil wars have proved a barren ground from which any famous or memorable book can emanate. The political novel will possibly rouse a yawn, and political poetry seems to have vanished with apartheid.

Part of the reason why nine out 10 undergraduates do not know a young writer from their generation is that their initial conception of literature is the rigid, pedantic and didactic form in which it has – and still is – taught. There has not been any loosening up so that Meja Mwangi can find his way to the classroom, even for a change.

It is always the same old individuals who, for all their professed timelessness, the digital generation cannot certainly savour in the same way some hotheaded young university students would have in the 1970s.

Secondly, technology seems not to complement literature accordingly. And, possibly, Africans are yet to settle and start appreciating art fully. We have many political and economic wars to focus on, rather than the niggling art-related problems.

In the meantime, Nigerian movies and music with not so much substance and glossy magazines from the South are being devoured in no small measure.

Themed beauty pageants and fashion shows are the new frontiers of art for women and European soccer the best leisure gift, seemingly to eternity. God forbid.

All these are highly commercialised and voyeuristic events with hardly any long-lasting instructive value.

The world has moved and everything has become instantaneous, and African literature would have done better and transformed itself accordingly. Moreover, young writers would have done well and packaged their material in the best way (electronic or otherwise) that can grant them timelessness.

Here is hoping that the Kwani? Litfest explains why the conflicts, which have invariably fed literature, are being given a wide berth by the new generation of writers.