Bosire has strong credentials but past Kanu ties could spoil for him

File | NATION

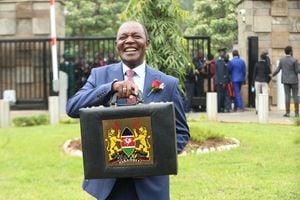

Justice Samuel Bosire at the opening of the Milimani Commercial Courts recently.

What you need to know:

- He will be a strong candidate but allegations that he may have benefited from controversial public land allocations may spoil his chances of becoming CJ

Justice Samuel Elkana Bosire is one of the well known members of the Kenyan Bench. That is principally because of his central role in two high-profile judicial engagements — the commission of inquiry into the Goldenberg scandal and the famous S.M. Otieno burial dispute.

Justice Bosire is also one of the most experienced members of the Judiciary. He entered service in 1976 as a district magistrate and rose through the ranks to become a High Court judge a decade later. After serving in the High Court for 10 years he was elevated to the Court of Appeal.

The judge is known as a supporter of arbitration and other alternative dispute resolution mechanisms especially on family disputes. His passionate commitment to family as a unit is reflected by his keenness to resolve marital disputes amicably.

This can be viewed as a positive approach considering one of the tasks of the new Chief Justice will be reducing the huge case backlog that has plagued Kenyan courts.

Ph.D dissertations

His rise to fame started when he presided over the S.M. Otieno case whose judgment he delivered in 1987. Books have been written and Ph.D dissertations done about the case.

Justice Bosire’s contribution to the law on this case and his influence on his colleagues in the law of burial is felt at home and abroad.

S.M. Otieno, a prominent Nairobi advocate, died on December 20, 1986. A Luo from the Umira Kager clan, Otieno was born and raised in Nyalgunga sub-location, Siaya district.

Soon after his death, a dispute arose between his widow Wambui Otieno (the plaintiff) on the one hand and his younger brother (the first defendant) and a clan member who was also the deceased’s distant nephew (the second defendant) on the other. The dispute concerned who had the legal right to bury the deceased and where the burial was to take place.

The defendants wanted the deceased to be buried in his father’s homestead in Nyalgunga, according to Luo customary law, while the plaintiff wanted the burial to be held at Upper Matasia in Kajiado district, where the deceased owned a farm.

The plaintiff argued, among other things, that Otieno had married her under the Marriage Act (Cap 150) and, having lived away from his ancestral land for a considerable period and having chosen a lifestyle consonant with Christianity and Western values, he was not subject to Luo customs.

Luo customary law

In the case which drew huge public interest, Justice Bosire ruled that the lawyer’s burial was not governed by any Kenyan statute, English common law or any English statute of general application in force as at August 12, 1897. The court was, therefore, left with the personal law of the deceased, which was Luo customary law.

In regard to the argument that Luo customs violated the Constitution in being discriminatory against women, he argued that this could not stand since the Constitution, in section 82(4), allowed for discriminatory rules in matters of personal law, including burial.

He concluded that both the plaintiff and the first defendant had the right under the Luo customary law to bury the deceased and to decide where the burial was to take place but, as they were in disagreement over that issue, justice demanded that the court give direction on the place of burial.

Justice Bosire ruled: “…change is inevitable, but that must be gradual. Times will come and are soon coming when circumstances will dictate that the Luo customs with regard to burial be abandoned. Until then courts will have to give effect to them in so far as they are applicable ...”

Looked at against his application for the Chief Justice job, the ruling portrays Justice Bosire as a judge who is conscious about change but is slow to embrace it.

At a time when the Judiciary is trying hard to align itself with the changing societal norms, the judge may find it difficult to abandon traditional thinking which has often brought the institution into sharp public focus.

End a circus

More recently, Justice Bosire has come to be associated with the Goldenberg Commission of Inquiry which he chaired. In appointing the commission, President Kibaki brought to an end a circus in the courts that had abjectly failed to prosecute the principal suspects.

Attorney-General Amos Wako terminated all court cases relating to Goldenberg, paving the way for the commission, which was empowered to hear evidence about the matter in open court.

The commission was appointed in the public interest “to inquire into allegations of irregular payment of export compensation to Goldenberg International Limited” and also to look into “payments made by the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) to Exchange Bank Limited in respect of fictitious foreign exchange claims”.

In its final report the Bosire Commission found that Sh158.3 billion of Goldenberg money was transacted with 487 companies and individuals.

A list of exhibits compiled by the commission puts Goldenberg International Ltd at the top of the primary recipients of the money, at Sh35.3 billion.

The directors of Goldenberg were named as Mr Kamlesh Pattni and Mr James Kanyotu.

The commission recommended that a number of high profile politicians and public officials should face criminal charges for their actions and that former President Daniel arap Moi be investigated further.

Justice Bosire’s leadership at the commission was not without controversy and at one point the judge threw out the two assisting counsel.

He kicked them out after Dr John Khaminwa and Dr Kamau Kuria’s conduct was questioned during the cross-examination of the star witness, Mr Pattni.

The two filed a suit under a certificate of urgency seeking to quash Justice Bosire’s decision to exclude them from the proceedings. They argued that their exclusion risked making the commission biased.

They questioned Justice Bosire’s decision to allow lawyer Pravin Bowry, acting for Mr Joshua Kulei, a former powerful State House operative, to conduct what they termed a legally “dubious and scandalous” type of cross-examination about them and then Director of Criminal Investigations Department Joseph Kamau.

The two obtained orders from the High Court directing Justice Bosire to reinstate them to the commission. Justice John Nyamu ordered Justice Bosire to allow the two to continue discharging their duties pending the hearing of a substantive suit.

Justice Nyamu said Justice Bosire had made orders outside his jurisdiction and that he ought to have given the two an opportunity to defend themselves against the allegations. The spectacle portrayed Justice Bosire as a high-handed and intolerant individual.

It will also be remembered that Nairobi businessman Muzahim Salim Mohammed sensationally caused the Goldenberg Commission sittings to be postponed for a week and later was put under 24-hour police surveillance. He was issued with a firearm after he claimed that his life was in danger.

The businessman had claimed that Justice Bosire had been compromised. The allegations were later dismissed and the Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission recommended that Muzahim be charged with giving false information.

Accused of bias

At one point the Goldenberg Commission’s assisting counsel accused Justice Bosire of bias, conflict and misconduct and asked him to step down.

However, the entire commission’s judges ruled that neither Justice Bosire nor the other members of the Bench would quit. They termed the plea “preposterous, lacking in merit and, in our view, made with intent to annoy”.

Still on the Goldenberg commission, Justice Bosire’s curious ruling that the commission had no jurisdiction nor was it necessary to summon witnesses has been the subject of wide condemnation and raised significant concerns.

The ruling was in total disregard of the Commission of Inquiry Act, Cap 102 Section 10 that provides that “(1) Every commissioner shall have the powers of the High Court to summon witnesses, and to call for the production of books, plans and documents, and to examine witnesses on oath.”

Further, the Act empowers such commissions to admonish those who refuse to appear before it.

However, a commission of inquiry does not have the powers to jail or pass sentences on any individual. Justice Bosire’s ruling effectively closed the door for otherwise valuable testimonies from potential witnesses if they had been summoned.

Subsequently, a suit was filed in court to compel the commission to summon witnesses and a three-judge Bench ruled that indeed the commission had powers to summon witnesses. However, on appeal, the Court of Appeal overturned the ruling.

These incidents left Bosire in professional embarrassment. As a judge of appeal, Justice Bosire was a member of a higher court than the High Court and he would ordinarily sit on appeal in decisions made by the High Court.

The embarrassment which was caused by the frequent challenges to decisions of the inquiry in the High Court led the commission to recommend in its final report that, in future, if the government should ignore the advice of the commission and appoint judges to inquiries, they should be from the High Court and not the Court of Appeal, to avoid exposure of judges of appeal to embarrassment.

Even after handing its report to the President, the Bosire Commission suffered a major credibility setback when the Constitutional Court headed by Justice Nyamu in the Saitoti Vs AG case ruled that the report had made 28 factual errors that the AG never contradicted during the hearing.

Worst of all, the judges accused the commission of ignoring evidence and exhibiting such clear bias that it could have never been accidental.

The judges accused the commission of creating “a pyramid of bias, discriminatory treatment of evidence, submissions and factual errors, partiality and unfairness”.

For a judge, no charge could be worse. The court also accused the commission of dereliction of duty, inconsistency of legal opinion, violation of public interest and abuse of office.

These flaws in the Bosire report were used by other accused persons in the Goldenberg scam to defeat their own prosecution and conviction.

A case in point is Eric Kotut, who got orders to stop all Goldenberg-related cases against him.

The trashing of the Bosire report has done mortal damage to the war against corruption because the unrecovered money will be used to acquire power and entrench graft.

And worse still the Goldenberg inquiry has left Justice Bosire’s credibility injured due to the shenanigans surrounding it and also given that a substantial part of it has been quashed by other judges.

More controversy was stoked when it was revealed in Parliament that those involved in the Bosire Commission were paid a staggering amount by the government. The commissioners and staff who ran the Goldenberg inquiry were paid Sh350 million apparently as a safeguard to them being tempted by bribes.

Justice Bosire received Sh56.3 million over two years, with seven other senior employees receiving a sum of over Sh200 million between them.

Looted money

The question that has remained in the public is, if the report of the Bosire Commission failed to help Kenya as a nation to get justice and the looted money, the approximately Sh2 billion spent on it will have gone down the drain.

And if conclusively trashed, Kenyans will never unravel the Goldenberg monster. And the commission will have provided a perfect forum for the suspects to launder themselves.

Besides the credibility dent he has suffered as a result of the Goldenberg commission, his conservative and sometimes rigid approach to issues may make it difficult for Justice Bosire to transform the Judiciary if appointed Chief Justice. There have also been loud murmurs that he has deep connections with the past Kanu regime and may, therefore, fail to inspire public confidence.

But, overall, Justice Bosire will be a strong candidate and among the front runners, especially given his experience and admirable leadership credentials.

His reputation as a church elder and a Sabbath school teacher in the Seventh Day Adventist (SDA) church in Nairobi will not do much harm either, but lingering doubts about his Kanu-era links and whether or not he benefited from controversial public land allocations, will hang, like an albatross, around his neck.