Controversy over inclusion of tribal identity in census

What you need to know:

- The question of tribe in the forthcoming national population census has put government officials and donors on a collision course after the officials defied the donors who have demanded that the question be struck out of the questionnaire

- Government ignores donor concerns that ethnic question in August population census will derail efforts towards national healing

A spirited attempt to block a census question that would make it possible for Kenyans to know the number of people in each of the country’s 42 tribes has been rejected even as it emerged that the government was planning to deploy monitors to help prevent rigging of the August national census.

Donors wanted the question dropped from the official census questionnaire on grounds that it will frustrate efforts towards national healing after last year’s bloody post-election violence.

The donors argued that the question will evoke memories of the killings, many of which were attributed to tensions between tribes following the disputed presidential election. Some 1,300 people were killed while 350,000 were displaced in the violence.

Ministry of Planning officials have decided to press on with the questionnaire bearing the tribe question, arguing that fears that it was too emotive were overblown.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics director general Anthony Kilele confirmed the donor concerns.

“They thought it might not be good for us to ask people about their tribes when they have not healed (from the deadly post-election violence),” he said.

But Mr Kilele said the donors’ fears had been proved wrong since the question had been answered well during a pilot census survey ahead of the Sh7.3 billion national count.

“We have established that all Kenyans are comfortable with answering the tribe question,” he said.

“The data (on tribe) is of good statistical value,” he said. “It will allow us to know better who we are, rather than relying on generalities.”

The donors had argued that it would be difficult for the results to be trusted if some of the results on the tribe numbers were disputed.

Their case was based on the reasoning that politicians and their communities would want to show that their tribes were more populous than the rest, in a bid to benefit more from devolved funds such as Constituency Development Fund, which are calculated on the basis of the number of people in each constituency.

So great are “rigging” fears that the government recently called on interested international and local firms to apply to monitor the exercise.

No census has been overseen by independent monitors in Kenya’s history, meaning stakes in this year’s exercise are high especially coming so soon after the controversial 2007 General Election.

The Kenya 2009 Population and Housing Census will be held on the night of August 24/25.

Tensions over the numbers of each tribe are not new. In 1999, the question was asked but data on the findings was not made public.

It is also expected that results of the census may guide the creation of new constituencies ahead of the 2012 General Election.

The donors’ concerns are similar to those recently raised by former Kenya National Commission on Human Rights chairman Maina Kiai who called for postponement of the census on grounds that the “high political temperatures” in the country were unsuitable for collecting population data.

There were also fears that there could be “rigging” in the exercise, with people deliberately distorting the count to inflate figures of their regions “to benefit from higher allocation of devolved funds and get new districts and constituencies”.

Allegations have been made that leaders in some parts of the country were preparing to import “outsiders” to their constituencies with the aim of boosting numbers to show a surge in their population.

But Mr Kilele pointed out that questions on identity were common all over the world. He cited the US which collects data on the number of African-Americans, whites and Hispanics.

He said there was danger that Kenyans will continue using data from the 1989 census to estimate numbers.

“It is dangerous for us not to provide the (tribe) figures since they are important for statistical and cultural analysis,” he said.

Data on tribe was last provided in the 1989 census.

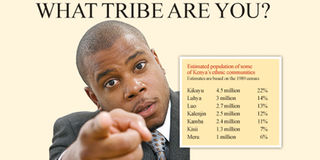

Out of the 1989 figures, it is estimated that the Kikuyu comprise 22 per cent of the population followed by the Luhya at 14 per cent.

The Luo are estimated to make up 13 per cent with the Kalenjin constituting 12 per cent of the population. The Kamba form 11 per cent while the Kisii and Meru are at six per cent each.

It’s these figures that the controversial tribe question seeks to confirm.

The question reads: “What is (your) tribe?”

Mr Kilele said data on tribe for the 1989 censuses and those before were all released.

According to the 1989 census, the Kikuyu comprised 4.5 million, the Luhya 3 million while the Luo were 2.7 million.

The Kalenjin were 2.5 million, Kamba (2.4 million) while Kisii and Meru were 1.3 million and 1 million, respectively.

The importance of collecting data based on tribe was also underscored by the director of the National Coordinating Agency for Population and Development, Dr Boniface K’Oyugi, who said it was a good measure of socio-cultural identity.

“There was a feeling (among donors) that the data was not needed given the current (polarised) situation in the country but we think we should have the information so we decide what to do with it,” he said.

It is understood that Planning minister Wycliff Oparanya intervened to have the donors back down. According to National Bureau of Statistics official Christopher Omollo, the donors were asking what the value of the numbers on tribe will be for the country.

The government side argued the data was important to reveal fertility behaviour of different ethnic communities, their education levels and other relevant facts.

“We are looking beyond just numbers. The donors were opposed to the question so we had to explain to them the reasons why we wanted to collect data on the issue,” said Mr Omollo.

The Sunday Nation learnt from one of the donors – United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) — that they were initially insistent that the question be dropped.

But they were later persuaded on its importance after talks with the government.

Some of the donors, under the banner of the Donor Consultative Group, that are jointly helping to fund the exercise include UNFPA, UNDP and western missions.

Moi university communications lecturer Julliet Macharia said there was no need to drop the key question since avoiding it would not help heal the wounds of last year’s General Election. She said Kenyans have been so divided that they would go to any lengths to know anyone’s tribe through their names.

“We should face the reality and sort out the problems that come with ethnicity rather that mess up facts in the census,” she said.

Information that comes from regions of the country is necessary for various statistical analyses. For example, data collected during the 2003 Kenya Demographic Health Survey showed that some regions had high fertility rates than others.

Although the national average number of children per woman was five children the average in North Eastern province was 7.2 children.

Western and Rift Valley had the second highest total fertility rate of 5.8 children per woman followed by Coast with 5.6, Nyanza (5.4) and Eastern five. Nairobi province had the lowest fertility rate of 2.8 followed by Central recording a rate of 5.0. Mr Omollo said collecting data on tribe was important to help in analysis of fertility behaviour.

The debate on whether to retain the tribe question represents another twist to the census debate, which has already been dogged by fears that people may interfere with its findings.

President Kibaki’s frequent creation of new districts, the scramble for devolved funds and current political polarisation are all factors that have triggered debate.