The man who made millions from investing nothing in railways

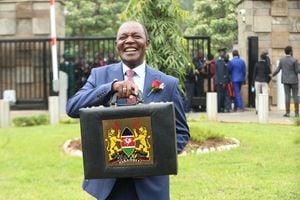

RVR managing director Roy Puffet and Kenya Transport minister Ali Mwakwere and Eng. John Byabagambi Minister for works Uganda (Right) during the launch of the Rift Valley Railways in Nairobi.

What you need to know:

- HARD QUESTIONS: How did highly paid technocrats in Kenya and Uganda and their World Bank advisers fall for a sham railways deal?

New evidence reveals how Mr Roy Puffet, the South African investor on the right who is at the centre of what is emerging as one of Kenya’s most infamous privatisation scandals, thrived by projecting the image of a big corporate player and director of multiple companies in South Africa.

But, as it was to emerge later, it was all but a clever game: most of the companies owned by Mr Puffet are shelf units with no capital base.

Just how he managed to commit Kenya and Uganda into handing over to him the running of the Kenya-Uganda Railways system for a period of 25 years is one of the intriguing aspects of the saga.

Tracking companies owned by Mr Puffet leads you to a complex web of holdings registered in Kenya, Mauritius and South Africa.

But the names of the companies that are material to understanding Mr Puffet’s intriguinng game are four: Rift Valley Railways Kenya Ltd, Sheltam Rail (Pty), Sheltam Trading CC (both of South Africa) and RVR Investments(Pty) of Mauritius.

Three interesting trends emerge from a closer scrutiny of the files of these companies from registries in South Africa and Kenya.

No capital base

First, they were all registered in the year 2005, only months before the railway transaction was concluded.

Secondly, none of the companies had a capital base to own an asset as big as the Kenya Uganda Railway system.

Mark you, the international valuation company, Ecorys Nederland BV, which was contracted by the two governments to specifically value the assets of the railway system, came up with a figure of $808 million.

Thirdly, none of Mr Puffet’s companies had either the capacity or the financial muscle to manage a railway system as large and complex as the Kenya-Uganda Railways.

What is clear is that the moment Mr Puffet’s consortium was declared the leader in the bidding for the concession, he went into a spree, registering one company after another in multiple jurisdictions.

According to information from the companies registry, Rift Valley Railways Kenya Ltd, the entity whose name appears in the actual concession document, was purchased off the shelves of Nairobi’s companies registry from two Kenyan businessmen, Philip Kingai and Julius Mwangi Ng’ang’a, on October 25, 2005 under certificate number 120151.

The two handed over this shelf company to Mr Puffet for a consideration of Sh200 million, hardly a week after the company was registered.

On November, 4, 2005, the name of the company changed to Rift Valley Railways Kenya Ltd. Mr Puffet and another South African national, Wesley Graham Kruger, were appointed directors.

According to the records, the share capital of the company was stated as Sh98,000.

At this stage, other names come into the picture, namely, RVR Investments (Pty) Ltd, an entity registered in the Republic of Mauritius, Sheltam Rail (Pty) of South Africa and Sheltam Trade CC, also of South Africa.

The shares held by Philip Kingai were transferred to Sheltam Rail Company (Pty) based in Port Elizabeth, while the shares owned by Julius Mwangi Ng’ang’a were transferred to Sheltam Trade CC.

With this multiplicity of companies in his hands, Mr Puffet was able to convince the government to sign deals with entities of doubtful financial standing.

It is noteworthy that, according to the concession agreement itself, the registration number for Rift Valley Railways Kenya is stated as C120 126.

Yet, in the files for the original company, it is given as C120 151. A mundane discrepancy? Maybe. But it serves to emphasize the point that the parties negotiating with Mr Puffet on behalf of the government did not do much of a due diligence process on the man and his companies.

A wily operative, the manner in which he committed negotiators of both governments to close the deal is a compelling story on the art of hard bargaining.

A few days before the day of taking over, and well aware that he did not have the $5 million he was required to cough up before moving into office, he crafted a clever scheme that enabled him to outmanoeuvre government negotiators and their advisers.

He carried on as if he was prepared and ready to meet all requirements until the very last minute, and thus cornered the government at a point where cancelling the deal would not have been a politically feasible option.

Mr Puffet’s game was implemented to precision. Up to the very last day, he gave no indication to the government that he did not have the money for the entry fees.

At one point, in those very last few days, Mr Puffet even asked the two governments to send wiring instructions to his bankers in South Africa so that the money could be sent.

The story goes how, one day before the day of closure, Mr Puffet was in Kampala attending a party hosted in his honour by the government to celebrate his imminent takeover of the railways. It was during that party that he broke the news to the government: he had just been informed that his most critical partner, Grindrod of South Africa, had pulled out.

The implication was that he was not going to meet a number of conditions for closure, including payment of entry fees.

Effectively, the two governments and their negotiators were cornered. It was too late in the day to cancel the transaction.

Spent the night

Consequently, top government officials of both Kenya and Uganda, flanked by a huge team of transaction advisers, spent the night at Kenya’s Treasury crafting a new agreement with new conditions to allow Mr Puffet to take over without having to meet all conditions of entry, including the entree fees.

He had won the game. Once he moved in, and having taken over as chairman and chief executive of the company, he signed a management agreement with companies associated with him in South Africa — allowing him to repatriate millions in fees.

The two companies were Sheltam Grindrod (Proprietory) Ltd and RVR Investments (Proprietory Ltd).

Under the agreement, Rift Valley Railways Kenya Ltd was compelled to pay Mr Puffet’s companies a management fee equivalent to two per cent of monthly revenues.

By tying the fees to revenues, he made sure he was able to earn millions from the company regardless of whether or not it was making profits.

In November last year, he sold Sheltam Rail to Egyptian private equity firm, Citadel Capital, making millions from investing nothing in Kenya and Uganda.