IDP boy’s four-year struggle to the top

Photos/SULEIMAN MBATIAH and FILE

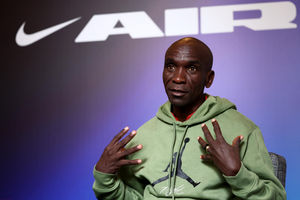

Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission commissioners and a UN official tour the Pipeline IDP Camp where top KCSE student John Njoroge has lived for the four years he attended secondary school.

When the post-election violence threw the boy’s parents and siblings out of their home in Molo into a camp for internally displaced people, he thought his ambition to become a doctor had been derailed.

But on Wednesday, all that ill-feeling was wiped out of John Njoroge who, now 18, has attended school over the last four years while his family lives in the IDP camp.

His is a story of struggle with seemingly insurmountable obstacles, including a threat to his life by a deadly disease, failure to raise school fees and eventual triumph over adversity to top his class.

The student from the Pipeline camp for internally displaced people that is 15 kilometres from Nakuru Town, is among those whose exam results were greeted with wild ululations as he was hoisted up the jovial shoulders of fellow villagers.

The brilliant teenager had scored an A in the national exams, and his future is shining as bright as star.

But just four years ago, John was a struggling teenager trying to overcome the trauma of inter-ethnic violence and watching his family forcibly ejected from their home in Molo District just before he joined Form One.

His family was evicted at the height of the violence and herded into a village of crammed tents, without the benefit of basic amenities like water and sanitation, together with hundreds of other families who shared their fate at IDP camps.

It is here that he has called home for the four years, and while the deplorable living conditions might be a tired old cliché for many of us, for John and other children, the reality of their situation hits them cruelly every single day.

This is especially so if one considers that they also have to attend school and are expected to perform just as well as other children, if not better, because education for a majority of them is the only way they can get themselves and their families out of the stranglehold of deep-rooted poverty.

The future might look bright for John, but in their closed-in and leaky makeshift tent that he shares with his family of six, he can’t help but feel some gnawing doubts; his family is too poor to afford higher education for him, even as he revels in his newfound stardom.

University bursary

And even if the Government stepped in with the statutory university bursary through the Higher Education Loans Board, it will still be a mountain to climb for the boy who is yet to clear a Sh60,000 fee balance at his former school, Anestar High School in the outskirts of Nakuru Town.

He is fearful that his former school may refuse to release his certificate should he fail to clear the arrears.

He also has to consider his living expenses in an unfamiliar city, and other costs such as books and clothing at the university.

The journey to the top has been fraught with challenges, including one time when he almost dropped out of school due to a life-threatening bout of pneumonia.

He was admitted to hospital for more than six weeks and this, he says, affected his performance: “I could have scored a better mean score, perhaps even emerged one of the top four students.”

“But I am grateful to God for the success, because without His grace I would not have been able to come out (of the illness) alive, much less perform as well as I did,” John says.

His father, 53-year-old Michael Njoroge Kaago, a manual labourer, who says he has faced an enormous task raising fees for his son through his meagre wages, is for the moment simply grateful that his son has defied all odds and achieved the “impossible”.

Sometimes, the family was forced to go hungry simply to keep the boy in school, he says.

In the end, John represents much more than a measly hope for his parents and siblings and his success in education might just mean the hallowed path out of poverty for the struggling family.

“Many children here simply dropped out or went through the motions to get a certificate because of the unique challenges IDPs face in camps. It is really not the ideal place to bring up a family, but many parents do not have a choice,” John’s father says.

Pipeline IDP camp chairman Paul Thiong’o also said that John’s success was a vindication of “our abilities despite our peculiar circumstances”, and added that John was a beacon of hope for many youngsters in the camp.

“It is high time the resettlement issue was settled with finality. I hope that it won’t be like this every other year, that children living in IDP camps struggle to find their names among the top performers in national newspapers. They should be accorded the same chance as everyone else,” Mr Thiong’o told the Nation.

John sat his KCPE at Kitigoi Primary School in Molo District, in 2007 and got 326 marks out of 500.

For now, his struggle through high school is a lot of water under the bridge, and he can only look forward to a future that may yet present its own challenges — or promises of greatness and prosperity for him and his family.