Tough girls take aim at Al-Shabaab militia

Photo/JARED NYATAYA/NATION

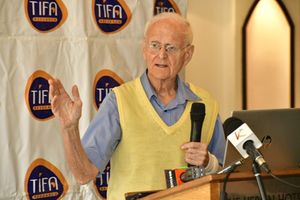

Caroline Lang'at, 23, from Nakuru (left), Phyllis Semo, 23, from Webuye (centre) and Claudia Mwilitsa, 24, from Kakamega.

Soldiers spend their entire lives training how to subdue the enemy in the shortest possible time, survive in the harshest of environments, and ultimately triumph over their adversaries.

For the Kenya Defence Forces troops involved in Operation Linda Nchi in Somalia, going after and subduing Al-Shabaab militants marks the highest points of their careers.

Though most of these are men, typical hardy soldiers whose lives revolve around fighting and conquering the enemy, a small number of them are women. (SEE IN PICTURES: KDF in Somalia)

Although they are not at Bur Gabo, a strategic town 60 kilometres inside Somalia that is the frontline, they have been at Ishakani, the camp that is the launchpad of the assault, and are raring to go.

Phyllis Semo, a bubbly 25-year-old from Webuye, thrice failed to qualify for recruitment into the Kenya Army at Panpaper Stadium near her home.

She opted to join the National Youth Service and was fortunate that the army decided to recruit from the ranks of the service in 2007.

They reckoned that if Ms Semo could survive the punishing routines at the National Youth Service, she was up to the task of taking up arms to defend her country.

“I was happy because I always wanted to join the army,” says Ms Semo, who is comfortable walking around at all times with the nine-kilogramme G3 rifle, which she had set aside for an M4 rifle at the time of the interview.

Caroline Langat, Ms Semo’s colleague at Ishakani, which is a short distance from the border with Somalia, also served at the NYS before she got the opportunity to join the army.

Ms Langat, a 23-year-old from Mogon in Nakuru, is shy and not as talkative as her colleague, but her eyes light up when she talks about life at the camp.

“It is a privilege to be here because I will tell my children about this when I am older and I will be proud to have done my part,” says Ms Langat, who is single but has a boyfriend.

Ms Semo interrupts: “You know, in future, children will be taught about the time Kenya finally decided to deal with the Al-Shabaab. I’ll be happy to tell them I was there.”

Ms Semo and Ms Langat are part of a crew posted to one of the observation posts at the camp by the sea, which has a view of the ocean at the point where the Kenya-Somalia border is marked by a large beacon in the water.

They said they were acutely aware of the perception among the public that Kenya’s peacetime army spent a lot of time training, and not fighting, and would be happy to disprove that.

The two, who have been at Ishakani since December 2010, have watched as the threat from Al-Shabaab grew and came to a head in September and October this year. (READ: Why Al-Shabaab loved Ras Kamboni town)

“We feel we need to show Kenyans that the army is for real and that we don’t spend all our time training and devising strategies,” said Ms Semo.

A soldier needs just a week to settle into a new environment, Ms Semo explained, and it was therefore not difficult to get used to life at the camp from which the operation to rid Somalia of Al-Shabaab started.

Ms Semo said when they learnt that troops from the 77 Artillery Battalion were headed out of Manyani to Ishakani, they requested to be included.

“We told our commander there would be no need for us to remain at the base and we needed to go to the front,” said Ms Semo.

They were eventually charged with controlling cross-border movement between Kenya and Somalia to keep out unwanted elements, a role they say they fitted into quite easily.

Because they are yet to settle into family life and the attendant commitments, Ms Semo and Ms Langat might not seem to be sacrificing much until you meet Rahma Osman Ali, Monica Mutunga and Claudia Mwilitsa.

The three are married, and being at the front has kept them away from their husbands, all civilians, for lengthy periods.

Ms Ali, a 25-year-old from Wajir, left her husband and three-year-old son for the war front, where she lugs around a nine-kilogramme rifle but loves the huge long-range guns she is trained to operate.

“I feel different because this is stuff I can see, not the theoretical training,” says Ms Ali. Her grandfather was a soldier, but none of her uncles followed in his footsteps, instead going into business and other jobs.

Ms Ali was the only woman selected from the three who showed up for the recruitment exercise at Barwaqo in Wajir Central in 2007.

Her colleague Ms Mwilitsa, also a mother of one, joined the army on the second attempt in January 2009.

“I always wanted to join the army,” she says when asked why she was here in the bush instead of the comfort of her home.

“I swore to protect my country and I knew that one day, one time, I would have to do what I have been taught in training,” said Ms Mwilitsa.

Rahma, Claudia and Monica become excited when the discussion shifts to the actual positions they would take when the time comes to fire their big guns at the Al-Shabaab militants at Kismayu.

The Al-Shabaab insurgents have been running away as the Kenya Defence Forces advance towards Kismayu, a strategic port town which they hope to capture and strangle the militia economically.

At Ishakani, the Nation news crew also found shy and reserved soldiers such as Grace Ngoru and Jackline Maore who politely declined to have their photographs taken for this story.

They, however, are acutely aware of the enormity of the task ahead and are pragmatic about the nature of the job that requires one to operate behind sand bags, observation posts and man roadblocks, in addition to carrying the heavy rifles wherever they go.

“When you are handed your gun and your ammunition, that means you are prepared for anything.

When I joined the Army back then, it was hard to imagine this would come to pass but it has and we have to do our job,” said Ms Ngoru, a shy 23-year-old from Nakuru.

But not all the women get to go to the front — one of Ms Semo’s colleagues had to remain at the base at Manyani as she had just returned from maternity leave.

All the female soldiers interviewed for this story are gunners, in the lowest ranks in their divisions, meaning they are a minority, a glaring testimony to the gender imbalance at the front.