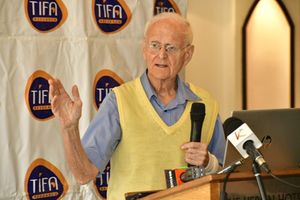

War veteran defied Kiir and doctors to witness big day

Photo/PHOEBE OKALL/NATION

South Sudan War Veterans Association Chairman, Lt-Gen Chagai Atem Biar, defied orders from President Salva Kiir, not to leave hospital in Nairobi to attend independence celebrations on July 9, 2011.

Lt-Gen Chagai Atem Biar is a military man who has lived all his adult life abiding by the rigid discipline that comes with that role.

Last week, he received an order he had to defy. The call was from the most senior general in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), Salva Kiir Mayardit, who told him that he was wrong to discharge himself from hospital in Nairobi to attend the independence ceremony in Juba.

Mr Kiir felt that Gen Biar should heed doctors’ advice and avoid travelling all the way. The old man’s reaction was defiant.

He had to witness the flag going up, he said, and if he died while watching that, he would leave the world a satisfied man.

Gen Chagai is a living embodiment of the huge cost at which independence of the South has come.

He has spent the last 58 years of his life immersed in the struggle to liberate his homeland, a period in which he has lost more relatives than he wants to count.

He is one of the most senior surviving members of the Anya-Nya liberation movement, which broke out in 1955 in protest at the way in which the colonial masters, Egypt and Britain, were handling the negotiations for independence.

The largely non-Muslim South wanted to be left as a separate entity from the North. Their demands were ignored and Southern forces waged a fight for independence that lasted a lifetime.

Throughout that struggle, Gen Biar held senior leadership positions in the rebel army and his status is reflected in the way he was feted around Juba on his arrival and by the ceremonial role he received as chairperson of the key committee preparing for the independence celebrations.

“As young men we grew up understanding that the best thing you could do was to fight for your people,” he told the Sunday Nation at the office of the war veterans association, which he heads.

“There was never a thought about taking up another career. Our course in life was set and we only wanted to fight for freedom.”

Gen Biar was there when a ceasefire was called in 1972 after the Khartoum government led by President Gaffar Muhammad Numeiry agreed to grant conditional autonomy to the South.

He was there when that agreement was repeatedly flouted, and was at Dr John Garang’s side when they told their people that time had come to go back to the bush to make one last heave for freedom.

Gen Biar was there when the command of the Southern forces was passed from Major Kerubino Kuanyin Bol to Dr Garang with the words uttered on May 13, 1983 that are well known to all members of the SPLA.

“Garang, the son of my mother, have you come?” Major Kerubin said.

“Take over the command from here. Chagai, my work is finished: give me something to drink and let’s celebrate the start of the revolution.”

Not fortunate enough

Many of the war veterans whose fighting record stretches back to the 1950s were not fortunate enough to live to witness the achievement of their dream.

Gen Biar was one of the exceptions and he planned to savour every moment. “It fills me with joy that people all over South Sudan have purchased a lamb to be slaughtered to mark this occasion. I have bought mine.

“And I ordered that when the flag goes up the blood of the lamb should be spilled to bless this moment in accordance with our traditions.”

Another, much younger, war veteran Deng Biar sat through the interview of his relative.

Deng’s story sums up the way in which the thread of the long war of liberation wound its way through several generations touching nearly every life in the South.

Deng was only 12 when he was recruited into the SPLA in the Twicis County of Dr Garang’s home state, Jonglei.

That was an age when one cannot have fully understood the reasons for the war and the SPLA used both soft power and force to gain recruits.

Promised good life

Chiefs were ordered to send a set number of youth into the army while recruiters encouraged volunteers with the promise of a good life once one joined the ranks.

“As boys we were told if you were in the army you would have a vehicle and your wife would also be driven to the market in a car,” he says.

But the reality dawned on them when they got into the bush to train. “Sometimes we would go without food yet we had to walk over long distances. But the worst thing was the thirst. Water was more important than food in that heat.

“Some people died while training without eating. In very desperate times you would borrow urine from your friend.”

Deng says the independence celebrations mark a moment too important to summarise in words. “What can one say when you are just too happy,” he said.

The older war veteran preferred to caution his countrymen not to get carried away with emotion. “The most important thing now is unity,” said Mr Biar.

“We must stand together the way we did during the referendum. We do not want any more disturbances. Even with our friends in the North we are saying we do not want more conflict. We now want peace.”