The gains and pains in effecting new reforms

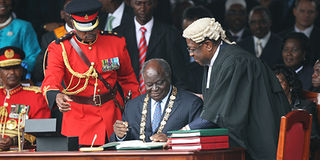

A new Constitution came into force at 10.27 a.m. on August 27 when President Kibaki appended his signature on the supreme law during a ceremony witnessed by a crowd which police estimated at 150,000. PHOTO/ NATION

What you need to know:

- There’s cautious optimism that Kenya is a better place now than it was under the old order but public remains anxious about the slow pace of implementing key changes

One year ago this week, Kenyans marked a watershed in the country’s history. A new Constitution came into force at 10.27 a.m. on August 27 when President Kibaki appended his signature on the supreme law during a ceremony witnessed by a crowd which police estimated at 150,000.

Much has changed since then. A lot of work remains to be done. But, in many ways, Kenya will never be the same again.

On the occasion of the first anniversary of the coming into force of the new Constitution, the Sunday Nation brought together a wide array of voices to reflect on the gains recorded so far and the path the nation needs to follow in the months and years to come.

The predominant message is one of cautious optimism. There is uniform agreement that Kenya is a better place now than it was under the old dispensation.

Basic rights are entrenched in the law of the land. The process of dispersal of power from an overbearing Executive is well under way. Appointments to public office are being done under a system that is one of the most transparent anywhere in the world.

Yet the public remains anxious about the slow pace of reforms in institutions that affect their lives every day; the land management system, the police force and the courts of law.

Writing an article on behalf of the President published in this edition, his adviser on constitutional issues, Prof Kivutha Kibwana, says President Kibaki is confident the reforms citizens yearned for will bear fruit and pledges to re-dedicate himself to the full implementation of the Constitution during his remaining time in office.

But the President also urges Kenyans to accept that the renewal of society will depend on a re-examination of national values and ethics and that change will come as much from the citizenry as the leadership.

“Implementation of the Constitution is not merely a matter of passing the requisite ordinary laws to give flesh to the basic constitutional principles,” he says.

“The law authoritatively expresses values that a country holds dear. To successfully implement our Constitution, we must live the principles and values that it establishes. We must transit into a country where the rule of law for all reigns. We must implement Vision 2030 in an equitable manner.”

Prime Minister Raila Odinga, who has spent most of his public life in the trenches in the fight for a new constitutional order, argues that the past year has already seen significant changes and expresses optimism that, if citizens are determined, they can ensure the successful implementation of the new law.

“The new Constitution is already changing the way we manage our affairs, giving a voice to minorities and the marginalised, and imposing tough integrity and accountability standards on those vying for public office,” he writes. “It is making unprecedented demands for transparency and accountability in the management of public affairs, and ensuring public participation in critical decision-making. Examples are recent judicial and government appointments, which have been achieved in a dramatically different manner.”

In some ways, both men are right. There have been significant changes during the past year, some of them hugely symbolic. Dr Willy Mutunga was once a political prisoner at the Nyayo House torture chambers. He was subjected to the sham trials that took place from 6 p.m. at the High Court before suspects were found guilty of being enemies of the Moi regime.

Now, Dr Mutunga is the Chief Justice, tasked with the heavy responsibility of reforming the Judiciary. The process through which he was picked is another clean break from the past.

The requirement for public interviews by an independent rather than hand-picked Judicial Service Commission places Kenya at par with nations with similar independent methods of appointments such as South Africa.

The Constitution has gone further than even those of advanced democracies such as America by calling for vetting of most senior appointees into public office by Parliament. That has removed the discretion presidents used to appoint cronies into key positions, a step many hope will lead to more transparent government.

Lean Cabinet

More changes will follow after the next General Election when the President will by law have to pick a lean Cabinet of no more than 24 ministers who will not be Members of Parliament.

Some complain that in certain sectors, change has come too slowly. Officials at the ministry of Lands have been accused of seeking to weaken the proposed National Land Commission by proposing legislation that would see them retain the powers that have made the ministry one of the most unaccountable in the country.

The ministry of Finance stands accused of trying to defeat the objectives of devolution and to retain more centralised control of public finances than the drafters intended.

According to Committee of Experts chairman Nzamba Kitonga, any efforts to undermine the new law will stand little chance of success because citizens have a right to petition the Supreme Court to assert the correct position.

Mr Kitonga says the real test of the new law will be whether it delivers on the promise of making the lives of Kenyans better as the implementation process moves forward. He says the counties will be key factors in this effort.

“It will cost money to establish counties and get them up and running. But they will become units of production which is a break from the past when districts just existed. All over the country, groups have been meeting to draw up development plans for their counties. There is huge potential there. I was in Ethiopia recently and the hosts pointed out that the benefits of devolution were most visible outside Addis Ababa. It is amazing how the capitals of the various federal units have grown since they embraced federalism. They have become mini-capitals. That is the long term view we should take.”

In one sense, the North Rift investment conference that concluded in Eldoret yesterday pointed the way to how the future economy will be shaped with regional groups seeking to take maximum advantage of the potential within their land and crafting plans to bring in investors to yield maximum benefits for residents.

There is no doubt that the achievements of the past year are worth celebrating. At a dinner hosted for some of the heroes of the second liberation last Thursday, Mr Odinga said the history of Kenya was the story of a struggle between progressive and conservative forces.

He said August 27 was “undoubtedly the finest moment in the struggle for a better nation”. That is hard to contest. But Koigi wa Wamwere and Archbishop David Gitari cautioned that the gains the nation has made can just as easily be reversed if Kenyans are not vigilant.

“If I was asked to summarise what the struggle for the second liberation was about in one sentence, I would say it was a struggle to make Kenya a multi-party state,” said Bishop Gitari.

“But we must never forget that at independence, we were a multi-party democracy. The Constitution was subsequently mutilated beyond recognition. It is true that the climax of the struggle was on August 27 when the new law was endorsed. It is a time to celebrate but also to guard against losing the gains.”