Tribalism and appetite for public resources to blame for our woes

What you need to know:

- In a bad election year, ethnic rivalry has wiped out as much as six percentage points of growth momentum.

- In Kenya, public resources over which this protracted war for control is being fought, lies mainly in three economic areas of public jobs, government tenders and public land.

- Kenya’s founding President Jomo Kenyatta started it all on a path in which people from his Kikuyu tribe rapidly occupied top government positions introducing the term “Kiambu mafia” in the national vocabulary.

- Billions of shillings worth of government tenders have been awarded to loyal tribesmen while illegal acquisition of public land by powerful private interests remains as vicious as it were at independence.

Every five years that Kenya goes to the polls, the country’s economic growth slows down by a margin of at least one and half percentage points; just about half the three percentage points estimated to be the cost a festering ethnic rivalry or tribalism exacts from the national output every year.

In a bad election year, however, ethnic rivalry has wiped out as much as six percentage points of growth momentum and lasted for two to three years before normalcy returns — as was the case during the December 2007 polls — framing the problem squarely in the economic rather than political or social space.

Yet Kenya has continued to mistakenly diagnose tribalism as a socio-political problem that can be dealt with through enactment of laws that target only the most basic expressions of the problem as is found in ethnic-based verbal vilification of others — commonly known as “hate speech”.

This Grand National pretence or blatant refusal to properly frame tribalism as an economic phenomenon is the reason politicians — even those well-known to be unapologetic practitioners — continue in the game while at the same time participating in public condemnation of it without feeling the burden of guilt.

The economic roots of tribalism have however clearly demonstrated the menace as it exists in the Kenyan national fabric is nothing but a protracted fight for undue access to and control of public resources — mostly through control of political (State) power.

That power has traditionally been concentrated in the presidency but has more recently got a new addition in the office of governor.

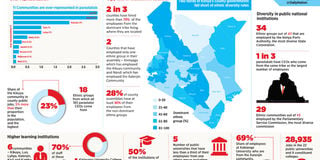

In Kenya, public resources over which this protracted war for control is being fought, lies mainly in three economic areas of public jobs, government tenders and public land.

WAVE OF ETHNIC VIOLENCE

It is the chaotic and mostly extra-judicial management of these resources that has inculcated in the ordinary Kenyan’s psyche the feeling that the game is rigged in favour of those whose tribesman or woman occupies the most powerful position in the land (and now in the county) — making the fight for these positions not only tribal but overly vicious.

The Waki commission formed to examine the causes of the apocalyptic wave of ethnic violence that engulfed Kenya after the 2007 election came to the same conclusion, writing in its report that use of State power to influence access to national resources “has given rise to the view among politicians and the general public that it is essential for a member of their ethnic group to win the Presidency in order to ensure access to state resources and goods.”

In Kenya, the mantra appears to be to mess up everything then appear to be shocked when it all comes down tumbling.

Take the fight over public jobs, for example. One of the reasons Kenya and Tanzania took and have remained in markedly different paths when it comes to ethnic rivalry is the distribution of top jobs in each country starting with the post-independence governments.

Kenya’s founding President Jomo Kenyatta started it all on a path in which people from his Kikuyu tribe rapidly occupied top government positions introducing the term “Kiambu mafia” in the national vocabulary.

Tanzania under Julius Nyerere had no such mafia from his native Butiama to colonise key government positions in Dar-es-Salam. He pursued a diametrically opposite direction of socialism, which though stifled economic progression, guaranteed social cohesion.

KIKUYU DOMINANCE

In Kenyatta’s post-independence Cabinet, for instance, five of the 16 positions were occupied by people from the president’s Kikuyu tribe. Kikuyu dominance of that post-independence government becomes even clearer when the list of top bureaucrats, top managers of key state corporations and heads of the security apparatus are added to the mix.

No such ethnic-based appointments were visible in Dar under Mwalimu Nyeyere where deliberate attempts were made to anchor merit and inclusiveness as the basis upon which senior public appointments were made.

It also helped Tanzania that land was owned by the state with citizens having only user rights as opposed to Kenya where use of state power to acquire and privatise public land began in earnest under the Kenyatta regime.

Successive governments in Kenya have followed the Kenyatta formula populating the top echelons of the State machinery with tribesmen upon taking power and leaving interesting patterns of shifts at the top every time a new regime takes charge.

Billions of shillings worth of government tenders have also been awarded to loyal tribesmen while illegal acquisition of public land by powerful private interests remains as vicious as it were at independence.

The chips all fall into place — revealing the logic behind what often appears a thoughtless practice of nepotism — when one looks at the list of 1,000 richest Kenyans which is dominated not by the many smart entrepreneurs, innovators and professional geniuses the country has produced since independence but by families of those who have occupied top positions in government.

WIN GOVERNMENT TENDERS

Similar patterns emerge when one delves into the data on Kenya’s biggest land owners and most successful businesspeople. It all belongs to those who have wielded state power and their cronies — that group of citizens that have disproportionately used political and executive power to appropriate public land and win multi-billion shilling government tenders.

Evidence as to whether tribalism is underpinned by the quest to gain political power for purposes of using it to access public land, for instance, lives in the archival records of how the Kenyatta regime dealt with the British-sponsored resettlement plan at independence.

Those records show top politicians and bureaucrats, acting even to the detriment of the millions of their landless tribesmen, used powerful positions in government to appropriate large tracks of prime land bought from departing British settlers with World Bank and UK government funds, planting the seeds of a land ownership problem that has persisted to date. Meanwhile, tenderpreneurship, a word that is probably Kenya’s own addition to the English lexicon, continues unabated producing unlikely millionaires whose only claim to fame is having a grip on the long nepotistic gravy train that runs through the State infrastructure to hundreds of cronies down the chain.

Meanwhile, the greed among key players coupled with their knowledge of the manipulation that goes on behind the scenes continues to generate fierce tender battles in the appeals boards and courts producing a paralysis whose extent remains to be measured.

More recently, improved data storage and analysis has made it possible to assemble evidence showing the direct link that exists between the intensity of ethnic rivalry (read tribalism), the level of corruption and ultimately the rate at which the economy will grow.

From the famous Goldenberg scandal of the early 1990s, through the Kibaki regime’s Anglo-Leasing scam to the current regime’s National Youth Service and Afya House scandals, corruption has proven to be a tribal affair that thrives in ethnic connections.

GRIP ON POWER

Take the Goldenberg affair for instance which happened in the early 90s. It all happened when the then President Daniel Moi had his strongest grip on power having populated key state organs with members of his Kalenjin community backed by a few non-Kalenjin loyalists.

That state of affairs provided enough comfort for the regime to plan and execute one of Kenya’s most damaging economic crimes whose impact lasted more than two decades — distorting the country’s fiscal and monetary policy space, causing the country big trouble with development partners and slowing down economic growth.

Anglo-Leasing, the National Youth Service and Afya House scandals have all taken a similar pattern maintaining an ethnic DNA in their planning, execution as well as defining the beneficiaries of the proceeds of corruption.

It is all the reason tribal hatred has, without exception been directed at communities whose elite control state power.

When founding President Kenyatta was in power at independence, for instance, the Kikuyu were the prime targets of tribal animosity. Then came the Moi regime and all the guns of tribal hatred, including those in the hands of Kikuyu, were directed at his Kalenjin tribesmen.

Then Kibaki entered the scene and talk of 41 against one, re-emerged leading to the carnage that followed the 2007 General Election.

Little evidence exists to support high levels of tribal hatred against communities that have not controlled state power. No wave of ethnic hatred of the proportion that the Kikuyu and Kalenjin have experienced with their men in power has plagued the Kamba, Maasai, Taita, Giriama, Kisii, Luhya or the Turkana from their North Western Kenya outpost.

RIGGED ECONOMIC SYSTEM

Failure to dismantle the rigged economic system (cronyism) in which those wielding political power use it to reward predominantly ethnic cronies is the best kept secret of Kenya’s tribalism machine, whose damaging effects on the nation-building project have yet to be fully fathomed.

Plausible estimates indicate the combination of tribalism’s workings against merit-based appointments to senior public positions — the resulting square pegs in round holes — the award of public tenders to unqualified bidders, and the opportunity costs suffered in the grabbing and hoarding of large tracks of public land by ethnic elite takes an estimated three percentage points of growth momentum from the national economy every year.

It is all the reason the electorate in the 2017 election must demand that all politicians running for public office participate in a frank and pragmatic discourse on the subject of tribalism that is removed from empty rhetoric and attacks its economic roots and logic.

This far, what politicians have done by way of enacting laws that only target tribalism’s symptoms such as ‘hate speech’ while turning a blind eye to “hate actions” - in the appointments to senior public positions, the award of tenders and appropriation of public land - is to game the system and refuse to even start the journey to ridding the country of this costly vice.