Prising young Kenyans from the ruthless clutches of depression

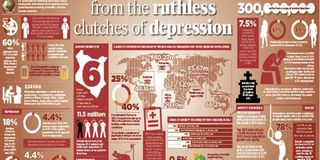

Suicide rates in Kenya are highest among its teenage population, caused almost exclusively by depression. Can we take the blues off this generation? GRAPHIC | NATION

What you need to know:

- Symptoms of depression in children and youth are irritation and anger - always misinterpreted as bad behaviour; it also manifests through low school grades and poor interpersonal communication

- A majority of depression cases in Kenyan children can be traced to school, where they are bullied by colleagues and punished by their teachers.

- Therefore, the physical ailment would be managed but not the psychological or psychiatric needs. This, the Ministry of Health believes, contributes to the many cases of undiagnosed and untreated mental illnesses, which lead to high disease burden, disability and mortality.

The youth clinic at Kenyatta National Hospital buzzes with life — texts coming in, people making calls while others leaf through the colourful magazines in the slightly cramped room.

There are young girls in school uniform, there are young men with dyed dreadlocks reading newspapers, and there are also parents and guardians who have accompanied their children to see the doctor. It is Tuesday, and they are here for their mental health review and check-up. The day before, a boy aged 10 had come to see Dr Josephine Omondi, a child and adolescent psychiatrist.

Eight in 10 of the youth who come to the youth clinic has one form or another of a mental condition. The clinic offers free services to these young ones. “It was clear he was depressed,” says Dr Omondi. “His face told it all.” “There are a lot of expectations in schools as they are academic-oriented. If this little child is not able to perform at par, the child is caned. The pressure breaks the child and they get these depression symptoms.”

These manifest as a drop in academic performance and poor interpersonal communication. Children, just like adults, are battling the dark, heavy cloud of depression. While most people recover from disappointment and failure and overcome them, those with depression take longer. Majority of depression cases in Kenyan children and the youth can be traced to school, where children are bullied by their colleagues and punished by teachers. Symptoms of depression in children and the youth are irritation and anger, always misinterpreted as bad behaviour.

“What parents should watch out for in their children and the youth is continuous feelings of sadness and hopelessness, social withdrawal, increased sensitivity to rejection, changes in appetite or sleep, outbursts and crying, as well as loss of interest in their hobbies, worthlessness or guilt and, at worst, thoughts to harm themselves,” said Dr Omondi.

She added that, in any given week, at least one patient is put on suicide watch. They confess that they were thinking of harming themselves but have not acted. Instead, they managed to share their predicament with someone. “Those who harm themselves commonly use rat poison, insecticides or fertiliser,” Dr Omondi disclosed.

“Secondary school children use a combination of Jik, Panadol, toothpaste and lotions.” But the wards at KNH, Dr Omondi adds, are not specially set up to handle such cases among the youth. Such facilities are available at Mathari National Teaching and Referral Hospital, which, Dr Omondi explains, is highly stigmatised as a “mental illness facility”.

Such referrals never end up there. “KNH needs in-patient care. These young people do not eat, they do not bathe, and they do not sleep. We need an in-patient care to handle such cases,” said Dr Omondi.

However, difficulty arises as to where to take them upon admission. “Do we take them back to school or home, where they might complete the suicide? They need to be admitted but we do not have a ward for the youth.” Currently, there are two severe cases at the clinic of young people who are suicidal but are at home because their parents cannot afford treatment in private care and cannot take them to Mathari because of the stigma.

MANAGING PATIENTS

This is just one in a litany of the inadequacies that plague mental healthcare in Kenya. Mental illness is likely to be misdiagnosed as other ailments such as malaria, migraine and stomachache, thus delaying crucial treatment for the nearly 11.5 million Kenyans with the mood disorders. Largely because most general practitioners do not lean towards psychological or psychiatric thinking, they would rarely look for the right causes.

Therefore, the physical ailment would be managed but not the psychological or psychiatric needs. This, the Ministry of Health believes, contributes to the many cases of undiagnosed and untreated mental illnesses, which lead to high disease burden, disability and mortality. Further, the staff to handle these illnesses are few.

Every ward in a referral facility needs a psychologist and every county hospital needs at least three of these at the bare minimum. There are about 88 to 92 psychiatrists in the country, most of them based in Nairobi. The other group of personnel are clinical psychologists, who are not medical doctors but use non-biomedical means to manage mental illnesses.

“At least five are qualifying every year but they are not absorbed by counties. They are the ones who would otherwise step in to pick out cases in schools and in county hospitals,” Dr Omondi explained. Finally, there are counselling psychologists, who manage the patients. They pick out the psychological stressors which cause depression and teach the patients how to cope with these stressors.

However, these specialists are barely trained, with the last national training conducted nearly a decade ago. Lack of funds and old medicines are also a concern that health workers in the public sector have to contend with in their bid to offer quality healthcare.

Moreover, the stigma around mental health is so high that rarely do parents take their children to the psychiatrist for evaluation, even when the children are depressed. “They come here as a last resort and, when they are referred here, they feel like they are being dismissed,” said Dr Omondi.

“Frequent questions they ask are: ‘Why are you sending me to a psychiatrist? My child is not mad.”’

Depression manifests differently in children and the youth. Some become clingy, crying all the time, while others wet their beds and want to be near adults.

There are also those who feel worthless and guilty. Dysthymia - persistent and mild depression - has been seen in children and youth. The person is able to work, carry on daily activities, but they are not performing according to expectation. At every clinic, between 40 to 60 per cent of those attending outpatient clinic are children. However, the child could be living with a chronic illness such as HIV, renal failure, cardiac disease, sexual abuse, is an orphan, or exposed to domestic violence or sexual abuse.

These children withdraw and become depressed because they are not happy with what is happening around them.

FOG OF DEPRESSION

By Judy Sirima Public Communications officer MOH

April 7 is known as the peak day to mark the anniversary of the founding of the World Health Organization (WHO). The theme of the 2017 World Health Day ‘’Depression’’ let’s talk brings our attention to the increasing number of people living with depression.

According to the WHO depression is an illness characterized by persistent sadness and a loss of interest in activities that you normally enjoy, accompanied by an inability to carry out daily activities, for at least two weeks. The risk of becoming depressed is increased by poverty, unemployment, life events such as the death of a loved one or a relationship break-up, physical illness and problems caused by alcohol and drug use.

Depression is an illness that can happen to anybody. It causes mental anguish and affects people’s ability to carry out everyday tasks, with sometimes devastating consequences for relationships with family and friends. At worst, depression can lead to suicide, now the second leading cause of death among 15-29-year-olds.

Clinical depression is a medical condition, similar to diabetes or heart disease. We need to stop making depression a moral issue. Is the person with a disorder of the pancreas or the circulatory system weak-willed, lazy or defective? Of course not. And neither is the individual who suffers from depression.

When a person has depression, it interferes with daily life and normal functioning. It can cause pain for both the person with depression and those who care about him or her. Doctors call this condition “depressive disorder,” or “clinical depression.” It is a real illness. It is not a sign of a person’s weakness or a character flaw. You can’t “snap out of” clinical depression. Most people who experience depression need treatment to get better.

A new estimate of depression released by the WHO reveals that the number of people living with depression has increased by over 18% between 2005 and 2015. Depression is also the largest cause of disability worldwide. More than 80% of this disease burden is among people living in low- and middle-income countries.

Between 1990 and 2013, the number of people suffering from depression and/or anxiety increased by nearly 50%. Close to 10% of the world’s population is affected by one or both of these conditions. Depression alone accounts for 10% of years lived with disability globally. In humanitarian emergencies and ongoing conflict as many as 1 in 5 people are affected by depression and anxiety.

What we see in the world right now — fear, anger, depression — we have concern that our neighbours near and distant feel safe and cared for, especially those who have increasingly been targets of threats or violence. Many factors may play a role in depression, including genetics, brain biology and chemistry, and life events such as trauma, loss of a loved one, a difficult relationship, an early childhood experience, or any stressful situation.

The growing number of depressed adolescents and young adults who do not receive any mental health treatment for their major depressive episodes calls for renewed outreach efforts, especially in school and college health and counselling services and pediatric practices where many of the untreated adolescents and young adults with depression may be detected and managed.

MACHO CULTURE

*Jane Kioko was 27 years old and was going through major problems both in her work and her personal life. She felt depressed, and even told colleagues she was going to commit suicide. No one took it serious until she committed suicide. If Jane had gone to a conventional doctor, she would most likely have been put on treatment and it might have brightened her outlook on life.

I have often wondered why it is so scary to be open about our frailties. With the revelation that depression and other forms of mental illness have a biological component, people should no longer feel that their symptoms are caused by personal inadequacies or a lack of willpower.

One of the major challenges of coping with a depressive disorder is dealing with the guilt and shame that one often feels about being depressed. Despite the fact that such celebrities as Ted Turner have publicly shared their battles with depression or manic depression, the stigma of mental illness remains.

I believe that the stigma surrounding mental illness arises from living in a culture where feelings of vulnerability are considered weak and unacceptable. This is especially true for men who are raised with the injunction that “big boys don’t cry” i.e. it is not okay for men to be vulnerable and show their feelings. This fear of being seen by themselves and others as vulnerable and weak, leads many men to lose touch with their own feelings and to avoid being in situations where strong emotion may be present. Women also suffer from this bias against feeling. If a woman works in a male-dominated field such as construction she is forced into the same mold as men. A woman working in a non-traditional field who feels and expresses her emotions is labelled as unstable, unreliable and weak.

Politics is another field, traditionally the province of men, now being entered by women, where vulnerability is unacceptable. In 1972, presidential candidate Edmund Muskie was considered unfit to hold office after he allegedly cried in public. I find it incredible that this bias still exists, given the fact that many great political leaders like Abraham Lincoln suffered from depression.

Abraham Lincoln is a particularly intriguing example of someone who achieved greatness in spite of the fact that he experienced bleak, despairing periods of depression throughout his life - no doubt brought on by the early death of his mother and cold treatment at the hands of his father. What he became and achieved after his illness is part of our great heritage.

The consequences of depression are as equally complex and varied as are its origins. Untreated depression often leads to decreased productivity, both at work and with everyday tasks, missed workdays, physical and emotional disability. The key is to realize that your individual worth and goodness is a function of who you are, not what you do. Most people who experience depression need treatment to get better. The good news is that depression, even in its most severe forms, is a highly treatable disorder. The best thing you can do for your family is to seek treatment.

Untreated depression can prevent people from working and participating in family and community life. Talking with people you trust can be a first step towards recovery from depression. Rather than judging yourself as “weak” or “defective,” you can learn to love yourself and to affirm your essential goodness. Feel free to have your therapist or a good friend assist you in making this shift in perspective. It’s okay to ask for help.

****

FACTS

Debunking myths

Not all depressed patients require medication as it depends on the severity — mild, moderate and severe. In mild we do not medicate; in moderate we can either medicate or not, depending on circumstances and the support system, says Dr Omondi.

When someone exhibits behavioural problems, they are deemed to culturally suffer from being bewitched, demon-possessed and they are taken to the pastor or priest for prayers. However, these are mental illnesses that can be treated and cured. It is good to appreciate spirituality, it’s a good support, but we should seek the right intervention on top of the prayers. Bring the child to hospital.

Among all mental illnesses, depression is the easiest to treat if we give necessary intervention and time and willingness to treat, she adds. Some people mistake one mental illness for another, such as depression. You can’t mistake malaria for pneumonia; perhaps, for others, it is a way of coping.

World Health Day 2017 is marked on April 7. This year’s theme is: “Depression. Let’s talk”.

Depression is a common mental disorder that affects people of all ages, from all walks of life and in all countries. The risk of becoming depressed is increased by poverty, unemployment, life events such as the death of a loved one or a relationship break-up, physical illness and problems caused by alcohol and drug use. Untreated depression can prevent people from working and participating in family and community life. Talking with people you trust can be a first step towards recovery from depression.

At a glance

For a child who is constantly bullied, the dilemma then becomes, how do we help this child to be able to fight back when other people are fighting them? Do you go overboard or do you tell them to be kind? How do we train our children?

Mental illnesses — such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, addiction disorders and impulse control disorders — stem from substance use such as tobacco or alcohol, psychological distress, impairments in social functioning among others. Others are genetic, that which contribute to imbalances in chemicals in the brain.