‘Jua kali artisans deserve the Nobel more than Ngugi’

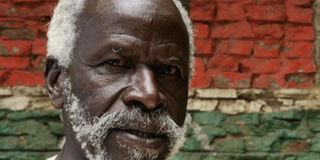

Writer and poet Taban Lo Liyong in a past photo. Photo/FILE

What you need to know:

- The professor was in Nairobi for the ‘East Africa at 50: A Celebration of Histories and Futures’ conference

- He was the first African to graduate with a Master’s degree from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop

At 77, he is surprisingly sprightly, and we had to literally run after him as he trotted across the University of Nairobi compound into the United Kenya Club, all the while giving us an impromptu lecture on the history of the campus where he taught in the 1960s and 1970s.

And as we groped in the dark tunnel below Uhuru Highway, he remarked wryly that one was damned if he went through it and doomed if he crossed the road above it because of the speeding vehicles.

We had earlier easily marked out Prof Taban Makotiyang Lo Liyong at the university’s Senior Common Room because of his trademark grey goatee and white thick woolly mane on his balding head.

Amid our futile protestations that even the richest man in Nairobi now walks on short errands because of the impossible traffic jams, he had reprimanded us, wondering why our employer could not afford to drive us to the venue of the interview.

After we secured a tentative truce, we raced to the club where, between several tots of dry double whisky, the controversial scholar regaled us late into the night with stories on books, politics and why he has no time for what he calls pseudo scholars in our universities.

The professor of African and European poetry, who is best known for dismissing East Africa as a literary desert, was in Nairobi for the ‘East Africa at 50: A Celebration of Histories and Futures’ conference.

The first African to graduate with a Master’s degree from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop told us why he would rather give the Nobel Prize for Literature to jua kali artisans than the current contenders, including Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

Q: Since the 1960s you have dismissed East Africa as a dry, desolate, barren stretch of wilderness where literature cannot sprout. What have you come to celebrate?

A: I was in second year at university when I wrote that. I specifically meant the absence of such high-level writing as Shakespeare and Milton. I thought a big guy like these would be born soon. The era of independence brought about fast publishing, but none of us was an independent thinker. Writers were second tier fighters against decolonisation.

We were playing second fiddle to politicians. We were really praise singers — adulators. Even (Prof Ali) Mazrui never saw anything ill of Nyerere, referring to him as a philosopher king, while Ngugi (wa Thiong’o) called Kenyatta a Black Messiah, which was the original title of his Weep Not Child. No politician is a philosopher king, they always have something up their sleeves.

Anglophone politicians sought answers from Nkrumah and George Padmore while the Francophone had the Negritude group. I have always said that political activism is different from literary creativity.

Q:Ngugi is being touted as a possible winner of the Nobel Prize for literature this year. Does he deserve it?

A: The farthest I have followed Ngugi is when I read The River Between, which is a rendition of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, and A Grain of Wheat — by far his best creation, a classic. But then he went down socialism and wasted a lot of time trying to become a political leader. I don’t know whether there is anything deeper in his new books. It is also interesting that nobody has written anything critical about his works.

But above all, this is a European prize and only they have the criteria.

I would have given Achebe or Léopold Sédar Senghor, but they said his most creative works were done earlier and then went ahead to award V.S. Naipaul for works he had written even much earlier. But it not should even be about the prize. The important question is: Does the chosen book speak on our behalf? What does it say about us? It (the prize) is given at the behest of Europe. If it were left to me, I would give the Nobel to jua kali artisans who do a lot to hoist the economies of their countries.

Q:You wrote The Last Word, then Another Last Word. Why can’t you conclude?

A: I will conclude when I die. I have just published my 16th book, Christmas in Lodwar. The setting of the novel is the town in Turkana where I spent my Christmas of 1979. You know I write to please myself. I write to communicate with myself. I write to unburden the angst.

Q:Talking of pleasing yourself, you have defied long-established literary conventions and even described the English language as a “prostitute with whom we have all slept in our different ways.” You come out as so indisciplined?

A: I am above discipline. I owe it to my grandmother Kiden Song’e, who was touching all over she couldn’t be stopped. She was even sold into slavery twice for her restless soul. I am Irimu the giant (the multi-eyed ogre in Gikuyu folk tales) and I want children to chase me, and if you can’t catch me, then you are not up to the task. Some of you are too reverential of Europe.

The white man was here (in Kenya) for too long, and even the economic development that you enjoy is an attribute of your Europeanness.

We fail to recognise that the white man, too, has flaws. We grew up in an era where we were saying let everything be interrogated, shaken and the luminaries tested. My job is to point out that the king is naked, if he is. The amount of time I have burned and energy I have invested intellectualising is enormous. At Iowa, I would write for 36 hours non-stop.

Even here at the University of Nairobi, where I had an office above the current bookshop, I would occasionally work until I slept there. Africa deserves the best.

Q:Which body of literature most fascinates you?

A: I am in search of intellectual satisfaction. What life is all about and how it could be lived well. I am a student of Shakespeare’s plays and poems, the main Greek playwrights (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes) and Homer’s epics. Bertolt Brecht and Amos Tutuola also fascinate me. Tutuola (author of The Palm Wine Drinkard) saw ahead of his time and imparted in us some of the wisdom, which we now see.

So what are you reading now?

I brought along the Uganda Journal of 1952. I like it because it has Lango origins and Basoga folk tales. I am also reading Voices from the Mountain: Personal Life Histories from Mt Elgon, which is edited by Masheti Masinjila and Okoth Okombo.

What is the place of motivational books in literature?

It is not literature. There is no place for it. Those writing about how people should make money are themselves poor. It is a money-making gimmick. I keep away from them.

Q:Presently, Kenya’s deputy President William Ruto is facing trial at the ICC and President Kenyatta is set to appear before it in November. Do you agree with the AU contention that the court is a persecutor of Africa?

A: We signed the Rome Statue because we wanted to be part of the world. Now we are trying to wind back the clock to rescue two people. People died and women are now widowed and children orphaned. These people did not die of magic. They were killed.

Now, even as we talk of bringing the cases back home, we need to think of the African context where when you kill somebody’s daughter or son, don’t you go with your clan and say you want to reconcile so that the blood of the dead is washed off your hands?

Q:Prof William Ochieng has accused you of making Nairobi your ‘Centre for Invective Dispensation,’ where you criticise every aspect of the ivory tower and leave the campuses aflame with clamorous debate. What fire have you brought this time round?

A: Tomorrow (last Wednesday) I am presenting a paper ‘It is tribal values; not tribal numbers that count.’ Watch out.

But in March, numbers did change the course of this country’s history.

Well, I wrote the paper last December, which was before the elections in March.

Prof Ochieng further says: “Taban no longer deserves publicity and can only be dotted as a museum piece. He lacks P’Bitek’s artistic bravura and Ngugi’s restless soul. He punches his colleagues without regard to reason.”

I don’t know what he is talking about. But you know he became a permanent secretary, and maybe he was speaking for the powers that were. He has, in the past, said he shed a lot of tears for Tom Mboya, but was silent on Robert Ouko. Why?

But some say you played safe yourself, not contributing much to the liberation of South Sudan by staying away at the time your country needed you most.

Some of us were justified to be circumspect because the various communities were suspicious. We did not know which way it would go. Dr John Garang was ambivalent about where he wanted to take the people. I think he wanted to be the president of a united Sudan, riding on the deaths of South Sudanese, and I was not for that.

When he came to South Africa when I was teaching there, I pushed him a note saying: “If you want to drag us to Khartoum, then give leadership to another person.” Even if he had lived to win, he would have been killed. God works in mysterious ways.

Q:The new nation seems unstable. What’s not being done right?

A: Garang had a tight grip and control of the army. He chose for his assistant a lowly educated person who never challenged him during the 21 years he was his deputy. (President Salva) Kiir is what Moi was to Kenyatta. But he is not as intellectually poor as people think as he is a graduate of military intelligence. Like Moi, he is only playing the fool among the PhDs.

Q: You lectured here when this was a campus of the University of East Africa. What are your recollections of the three East African leaders of the time?

A: Nyerere appropriated some of the resources meant for the college to the University of Dar es Salaam. (Dr Milton) Obote was a fool who led a strike at Makerere because of food. Regardless of his poetic mind, he had second-rate brains.

Q:You masqueraded as Ugandan for many years. Some would find this uncharitable for a country that brought you up.

A: I did not masquerade as a Ugandan. I was carried to Uganda as a baby to escape an aunt who wanted to kill me. I lived my full life there as a citizen. I went to Samuel Baker School in Acholiland and trained as a teacher at Kyambogo in Gulu as a Ugandan. I fought for Uganda’s independence as a Ugandan. I won a scholarship to America as a Ugandan. I was even an official of Obote’s UPC party. I denounced Ugandan citizenship and tore my passport after I came back from Papua New Guinea and found Idi Amin had come to power.

Q:You project yourself as a global citizen, yet you retreated to your village and became an MP in Juba during President Numeiri’s rule between 1982 and 1985. Was that not a diminishing role?

A: If you can’t have a local centre, then you can’t have a claim to a global position. Even Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea and people knew him as the son of Joseph of Nazareth. In my thinking, I am international, but when it comes to doing something for the betterment of the people, I go to the local place.

Q:In your play ‘Showhat and Sowhat’, you seem to celebrate wife-swapping as a catalyst of national cohesion, almost suggesting it as the answer to Kenya’s violence.

A: Symbolic writing is different from realistic writing. I am talking about a marriage of cultures. I wrote that book specifically for Kenya and South Africa. There is a parallel between South Africa’s Khosa and Kenya’s Kikuyu on the one hand, and the Zulu and the Luo on the other. Look at Kenya’s Indians for example. They largely don’t integrate sexually with other Kenyans and that should change.

Q:You have said Africa is frustrated because it has been sexually starved. What do you mean?

A: I drew that from Kuku mythology. What I meant by that assertion is that Africa cannot possibly take off unless it has suffered enough. Have we suffered as much as the Jews? No. Have Kenyans suffered as much as South Africans? Unless fire reaches the innermost part, we shall only be mediocre.

Q:As a modern intellectual, what justifies your marriage to five wives?

A: There are more girls than boys in our society. Don’t you have pity for the girl child? When a man marries, he pays dowry. Do you want the dowry to go to waste if he dies in war? But more seriously, literature is my first wife and she holds me tight. If all of us were to be married to our professions, there would be fewer problems.

Q:You founded the department of literature at the University of Nairobi in 1969 together with Ngugi, Owuor Anyumba and Okot P’Bitek. Today, no much debate is coming from there. What ails the department?

A: We left the war half-way, a war we did not win in 1969. We did not produce captains to complete the war. We were really amateurs. We were just writers. None of us was a literary scholar. There was no intellectual solidity. We were just promoters of literature, but not really professionals. The debate has died. Is it not shocking that Moi, Egerton and Kenyatta universities have never organised a conference on literature, yet there are literature professors there? Only when I come do we talk again.

Q:Is this why you have said you are fed up talking to yourself?

A: Nobody has studied my books to interrogate me since 1965. Nobody has followed the arguments; I am always explaining myself. I feel that I have not been taken seriously. I am frustrated. I feel let down. The so-called intellectuals have been seized by the tribal god. They are pseudo-intellectuals, whose knowledge can’t apply because it is irrelevant. They are conveyor belts.

That is why we are telling them don’t vomit on us the vomit of the white man. I have always thought that those of us identified by America and assigned American supervisors at universities were taught to criticise Mother Africa and its leaders. Only (former Central Bank Governor Duncan) Ndegwa has reflected on Kenya outlook through the eyes of a civil servant.

(Mr Ndegwa’s memoirs Walking in Kenyatta’s Struggles: My Story is considered one of the most illuminating stories to have emerged from former government insiders.)