Education sector poses the toughest test

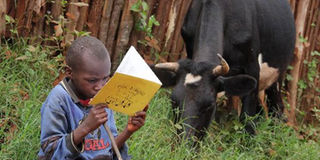

Christopher Kabiru enjoys reading a textbook as he looked after his parents' cow at Thunguma village in Nyeri on June 28, 2013. Children from public schools from all over the country spent a third day at home as teachers continued with their nation-wide strike pressing for higher pay. Photo/ File

What you need to know:

- But to achieve such a feat, it will need to employ more teachers first to meet the yawning gap of more than 80,000 countrywide before embarking on the ambitious strategy to decongest crowded classrooms.

So far, the education sub-sector in Kenya has probably posed the greatest governance challenge for President Uhuru Kenyatta’s three-month-old regime.

The move to implement one of its campaign promises — provision of solar-powered laptop computers for children in Standard One across the country — and this month’s teachers’ strike have particularly tested the leadership of the top brass of the Jubilee government.

While the President has passionately defended the laptops project and plans are underway to have it rolled out in public schools across the country, pundits have viewed his labour of love as something out of touch with the immediate needs of the sector.

The government has already earmarked Sh53 billion for the implementation of the project, to be phased across three years starting January 2014 at a cost of at least Sh17 billion for each of the phases.

Electricity grid

An initial report prepared by the Ministry of Education shows that the target is to reach 1.3 million pupils, with the targeted schools expected to be roped into the national electricity power grid, thereby opening up rural areas for development.

Other than the 1.3 million Standard One primary targets, the laptops will also be available to other learners in beneficiary schools, notes the Ministry of Education.

“After several consultations on how to implement the project, it has been recommended that a whole school focus be taken so that 8.75 million children access the laptops instead of only 1.3 million Standard One pupils,” the ministry clarifies.

Priority for selection will be based on the e-readiness of the school in terms of availability of electricity and classrooms, and secure storage of the devices.

By next year, if the project is implemented according to plan, some 6,275 primary schools will benefit in the first phase, another 7,046 primary schools will be covered in 2015 and an equal number in 2016, when the programme ends.

But according to education expert Andiwo Obondoh of the Centre for Social Sector, Education and Policy Analysis, the idea of laptops is “utopic and populist”.

Mr Obondoh notes that no one can deny the great need for technology, and that the fundamental need for acquisition of such skills early in life is essential to drive Kenya into a sustainable knowledge economy, “but our level of preparedness for such an ambitious project, based on e-readiness assessment and review of other competing and pressing priorities facing not only the sector but the nation at large, is what sector professionals are questioning”.

“This project has put the education priorities of the new Jubilee government into question because a good administration must get down to the basics first,” adds Mr Obondoh.

Many feel that there are more immediate needs in the sub-sector, like increasing the amounts allocated to the Free Education Programme that is benefiting millions of children in primary and secondary schools across the country.

For instance, every child under the Free Primary Education programme is allocated only Sh1,020 per year to cater for all their learning needs, while at the secondary level each student is allocated Sh10,265 annually.

These amounts, interestingly, have never been reviewed, nearly a decade since the launch of the FPE programme in 2003 and the secondary plan in 2008, despite inflation and the rising cost of goods.

Disbursement of the funds to schools has also been erratic, forcing school managers to borrow supplies and sometimes end school terms prematurely.

“All these are not happening because of lack of laptops in schools,” says Mr Obondoh. “The Jubilee government should focus on these basics first and rethink its computer-for-schools strategy.”

But last week, during a media breakfast meeting at State House, Nairobi, President Kenyatta said he was not ready to rethink the strategy, or even channel the funds allocated to the programme to other pressing needs like employing more teachers for the crowded classrooms in public schools.

“Anyone who tells me to divert the money — which we are borrowing in the first place — has his or her priorities inverted,” the President said.

As the debate over laptops rages, teachers say the want more money in their pockets, not computers in classrooms. Their industrial action, called off Wednesday after weeks of agitation, paralysed learning so much that there were calls for the extension of the school calendar to compensate learners for the time lost.

Teachers were demanding that the government honours a deal they signed in 1997 for increased allowances — medical, housing and commuter — calculated as a percentage of their basic salaries, which amounts to Sh47 billion.

But President Kenyatta told them his government had been in office for only three months, and that it would be unfair to ask for a Sh47 billion payout at once.

In return, his government offered the striking teachers a Sh16.2 billion deal, phased out in three years and signed by the Kenya Union of Post-Primary Education Teachers. However, the larger teachers union — Kenya National Union of Teachers — rejected the deal, deepening the education crisis in the country.

The government also plans to employ 10,000 teachers for public schools in a bid to meet the conventionally accepted standards of 40 pupils per class.

But to achieve such a feat, it will need to employ more teachers first to meet the yawning gap of more than 80,000 countrywide before embarking on the ambitious strategy to decongest crowded classrooms.

Many education promises captured in the Jubilee manifesto are yet to be reviewed, among them the plan to increase the transition rate from primary to secondary schools to 90 per cent, since a national exam is yet to be written under the new administration’s watch. Currently, the transition rate stands at 74 per cent.

Deputy President William Ruto says this plan will be achieved by “expanding the number of post-secondary places to give fresh secondary school graduates tertiary qualifications”.

Government secondary schools will admit half of the students from public primary schools while boarding schools in pastoralist areas will be increased to keep as many children as possible in class.

Bright students from poor backgrounds will benefit from a government-funded scholarship scheme that will see them get free admissions to the best schools, says the Jubilee government, while a business bursary scheme will be established and private companies encouraged to contribute to the kitty through tax incentives.

Private investors will also be given incentives to set up more schools that will increase the chances to post-primary institutions.

Institutes of technology

At the university level, the Jubilee government plans to reverse the elevation of mid-level colleges into fully-fledged universities.

Already, Mr Ruto has noted that money has been factored in the current budget to set up an institute of technology in each of the 47 counties.

More than 30 mid-level colleges have so far been elevated to university-college status, most of them under the Kibaki regime, and are awaiting further elevation to fully-fledged universities as it is envisaged in the First Sessional Paper on Education (2005).

But the elevation of the colleges will be shelved and, instead, the government will open new vocational technical institutes in each constituency.

Jubilee has pledged to sponsor qualified students through university, with a one-year work commitment in return, and also introduce free milk for all learners. None of these, though, has been actualised.