Young, restless and broke life in the eyes of Kenya’s youth

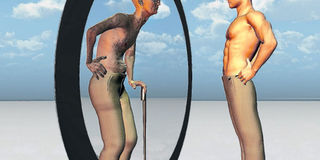

Forget mid-life crisis; there is a bigger, more sinister monster, and it is called quarter-life crisis. If you doubt it, ask Kenya’s 20- and 30-somethings. PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

You start realising that people are selfish and the friends you feel you have lost touch with are actually the most important. What you do not realise is that they, too, are not really cold or insincere. If anything, they are just as confused as you are.

If you do not have a job yet, the excitement you had at graduation wanes as days go by and you realise no one is calling to ask about the CV you dropped at their offices.

You are an adult. And broke. Terrible combination.

Faced with many uncertainties, 20-somethings are at constant odds with themselves. Being in your 20s is a lot like hanging off the edge of a cliff. There, you can’t afford to panic. You just have to focus on not dying and hoisting yourself up to the secure ledge.

After teenage years spent in angst over the lack of freedom that comes with living under your parents’ roof, you finally have independence.

Now what? You could be plopped into a new world and suddenly come face to face with the slightly terrifying pressures of making something of your life. Soon, you realise that you really do not know what you are doing.

If you have a job; it is not even close to what you thought you would be doing. You are going to have to start at the bottom, and you are scared. It worsens when you get your payslip and notice that half of it is swallowed by huge tax deductions and loan repayments.

JUST AS CONFUSED

You start realising that people are selfish and the friends you feel you have lost touch with are actually the most important. What you do not realise is that they, too, are not really cold or insincere. If anything, they are just as confused as you are.

If you do not have a job yet, the excitement you had at graduation wanes as days go by and you realise no one is calling to ask about the CV you dropped at their offices. You are an adult. And broke. Terrible combination.

Matters get complicated in your love life too. You get into many relationships only to marry the wrong person and spend half a decade in divorce or child maintenance suits.

Worse still, the language of love (or lack thereof) is no longer coated with sweet-scented, scintillating words, but the wads of cash in your wallet.

Around this time, you start getting calls from parents detailing how beautiful and intelligent your agemates’ offspring are. Your parents’ favourite refrain will grate your ears: “You want me to die without seeing my grandchildren?”

MORE DISAPPOINTMENTS

Higher expectations breed more disappointments and disillusionment. This often coincides with the Higher Education Loans Board (HELB) reminding you to repay your loan, for which they are fining you Sh5,000 monthly because you defaulted.

Meanwhile, your colleagues who went to tertiary colleges or joined the military are buying houses, getting married and living life; you begin to question your life.

Damian Barr, in the book Get it Together: A Guide to Surviving your Quarter-Life Crisis, describes these feelings perfectly.

“You may be 25 but feel 45. You expected to be having the time of your life but all you do is stress yourself about career prospects, scary debts and a rocky relationship.”

Barr gets even more blunt, saying “if your life was a movie it would go straight to Netflix, but nobody would rent it. Not even you.”

EXPECTING MORE

Harsh, isn’t it? Admittedly, Barr captures his own crisis in chapter seven, explaining that “there could have been a lot of red eyes at graduation, but maybe it would have managed my expectations. I’m 25 but am working in a largely unrelated field, having just left university”.

Dr Ruth Wanjau notes that these crises are happening earlier, especially among Kenya’s 20- and 30-somethings.

“The younger generation expects more than their parents did, but it is also harder for young people today than it was for their parents”, explains the chemistry lecturer at Kenyatta University.

Dr Wanjau observes that during her time, her colleagues “did not have to fight for their first job in a depressed global economy, and banks offered mortgages without asking for a huge monetary guarantee”.

Alice Mwangi, a graduate working in a local bank, is going through the exact opposite of what Dr Wanjau went through when she was young: “I’m 24, I have a degree but after countless interviews I still have no luck. So I’m stuck with a job I don’t like, swim in my overdraft and live with my parents, who at my age were married with a house and children.”

Vincent Momanyi, a 24-year-old medical student, says he frequently questions what he is doing and feels “trapped knowing that my career is set out for me”, while soft engineering student Gordon Okello, also 24 and the brains behind mobile app QuickLinks, has faced similar struggles.

“Every day I see a million reasons why I am likely to fail,” he admits. “In starting my own company I have made my own crisis and have set myself on a long and uncertain road, prolonging the feeling of gut-wrenching fragility.”

The confusion experienced by this group could be traced to high school, as Prof Joseph Nyasani of the University of Nairobi notes.

“A large number of university students are studying what they do not like, and end up, so much later in life, making a career parallel to their training,” notes the author of 36 titles and several philosophy papers.

Prof Nyasani explains that, unlike in the past where life was almost a pre-written script, today, it is more about luck, which has heightened anxiety, confusion, and inability to make relevant choices. Higher education is becoming more expensive, and its degrees less distinguishing.

“Parents are expecting more than ever before. They do not want to associate with their children who do not have money. In fact, they scorn them for being dumb and lazy,” says Mohamed Hassan, a businessman.

COMPARISON CRISIS

Former US president Theodore Roosevelt said that comparison is the theft of joy, and indeed those in their 20s lack the joy. In comparing themselves with friends and if their achievements and goals match up with theirs, it gets maddening to go on Instagram and see photos of their holiday in Dubai, or a honeymoon in San Francisco’s Robert Louis Stevenson State Park.

You find yourself becoming judgmental. You might find yourself thinking snide thoughts about developments in your friends’ lives; like “what’s so great about being married at 22? How boring!”

You might even compare yourself with your parents and what they had achieved by the time they were your age. And finally, you may compare your current life with your own expectations of what you thought it would be.

“No one prepares us for post-university revelations,” says 23-year-old Julia Kivanga, a final year sociology student at the University of Nairobi. “Ddream jobs don’t exist, and even finding any job you would want to do is virtually impossible.”

Nikki Elot, 27, who runs Mwangaza Girls Education Centre in Samburu, lived and worked in London for five years and admits she suffered — and thankfully survived — the quarter life crisis.

“I would describe what I went through as a prolonged identity crisis,” she says. “Having been defined by education up until 22, it was very difficult to find my place in the real world. Aspects of my life suddenly didn’t count in the same way.”

She has now found joy educating girls and saving them from early marriage.

Elsewhere, Phoebe Onwong’a, 25 and currently in a ‘dead-end job’ in a supplies company, confesses she’s panicking: “I recently wrote down goals I want to achieve by the time I am 30... and it’s terrifying how little time I have left,” she says.

TIME TO SETTLE DOWN

Social pressure to achieve personal milestones in life as early as possible has never been stronger. When a young woman surpasses the 25-year-old mark, she becomes the subject of cruel speculation if she hasn’t found Mr Right. Men, on the other hand, may well be accused of being sterile. Or worse.

Freshly Mwadeghu, 29, agrees that three decades ago, the youth were able to comfortably enjoy marriage, jobs and babies. Fast-forward to today, Mwadeghu asserts, and at the same age we are paying through the nose to simply exist in Nairobi and would jump at the chance of owning a kiosk in our apartments.

“In fact, most people under 27, when asked, have no plans of having babies,” he says.

Clinical psychologist Lucy Ngatia warns 20-somethings not to entertain confusion, but rather start planning their lives right now.

“Find the right partner as soon as possible, soul-search on your passion, get committed to your goals and work hard,” Dr Ngatia advises, adding that people in their 20s are not moving forward with their lives because they are lazy and indecisive.

However, her colleague, Rachael Lozi, a professional counsellor, believes there is an upside to forcibly delaying your future.

“Deciding to share your life with someone should not be an arbitrary goal. Marrying and starting a family as soon as you can is no guarantee of happiness. Arguably, you are better prepared if you mature as a single adult, instead of starting a family when you are still growing up. You can’t hurry love.”

CONFUSED IN JOBS

According to Deloitte Kenya’s Shift Index survey, 80 per cent of Kenyans are dissatisfied with their jobs. And while some unhappy employees muster the courage to change careers, others opt to grin and bear it.

“In the waning economy, company-downsizes have put many workers in an unexpected predicament” explains human resource expert Faith Mwendwa. Young employees who get laid off are forced to re-evaluate their lives, and many are turning to entrepreneurship, which just adds to their uncertainties, Mwendwa explains.

As Economist Edwin Mwai observes, “with the unemployment rate apparently stuck at double digits, more people seem to be choosing a passion they are confused about or stay in jobs to survive”.

Father Dennis Ekeno, a Catholic priest, advises that when you worry so much about work and money, they seem to be running further from you, and so “the best thing is to love what you do and put more effort”.

“God always blesses those who give their best,” he adds.

DISENGAGED WORKERS

But many Kenyans do not really love what they do. In a 2014 State of the Kenyan Workplace study by Moi University Human Resource specialists, 70 per cent of the 7,000 people surveyed described themselves as “disengaged” from their work. Those who show up at work but are “disengaged” made up the biggest category, at 52 per cent of workers. The remaining 18 per cent were actively disengaged — those who vocally express their discontent in the workplace.

The study takes a close look at the role of managers and their ability to inspire workers. Most of the discontent stemmed from “bosses from hell” who didn’t foster talent, growth, or creativity, especially for the recent graduate to join their companies.

In the long run, it was estimated that between Sh250 billion and Sh400 billion is wasted annually because of “bad managers” and disengaged young workers who hate their jobs. These losses arise from laziness at work, errors, truancy, conflicts and theft.

While these employment, career, relationships and growth issues may reinforce the suspicions of young adults that they are not formed of special clay (the power of the youth), the challenges they face, by themselves, may be a sign of early mastery without mature constraint, self-discovery at a moment when each revelation seems unique.

But, everything notwithstanding, the crisis rages on.