Show me yours and I’ll show you mine…

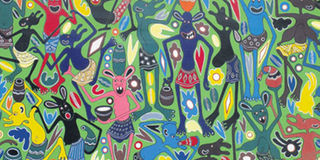

Painting of Shetani by George Lilanga. PHOTO | FRANK WHALLEY

What you need to know:

- Many collectors prefer not to lend anyway. Good pictures become friends. You live with them and are reluctant to part, even for a short while. So it’s a risky business.

- The art world can be a snake pit, riven with envy and petty jealousies.

- But at the end of the day we are left with the fact that a privileged few who have the best should have the common decency to share it with those who want but cannot afford; who aspire but cannot find; who do not know but genuinely seek exemplars and guidance.

I have often thought it would be instructive to hold a series of Collector’s Choice exhibitions, featuring some of the many exciting works in private hands throughout East Africa.

They could be from single collections, following the twists and turns of the owners’ tastes, or themed with examples from many private holdings. That would be no small thing.

There are rumours, for instance, of a Breughel among family treasures that happened to end up in Kenya and there are many fine works by the best of this region’s artists on private walls, snapped up by collectors and connoisseurs — not always the same animal — bought straight from the studio before they reached general exhibition.

A couple of very well known Kenyan politicians were avid collectors. It would be fascinating to see that side of men (in this case) known more for their forthright opinions about how we should live than for their quiet appreciation of a well drawn line, and colour.

One Kenyan industrialist is reported to have a group of Indian miniatures that would overshadow many a national museum’s.

Of course, there are difficulties — insurance, the risk of damage or theft, scrutiny by tax authorities ever ready to appraise hidden wealth, plus the natural reticence that attends such surreptitious accumulations.

Many collectors prefer not to lend anyway. Good pictures become friends. You live with them and are reluctant to part, even for a short while. So it’s a risky business.

The art world can be a snake pit, riven with envy and petty jealousies.

But at the end of the day we are left with the fact that a privileged few who have the best should have the common decency to share it with those who want but cannot afford; who aspire but cannot find; who do not know but genuinely seek exemplars and guidance.

Given that our national museums often lack the resources to buy the best and display it properly, it is left to the private sector to take up the challenge.

There is one gallery already leading by example. Hellmuth and Erica Rossler-Musch who own and run the Red Hill Art Gallery off the road to Limuru west of Nairobi have been collecting African art for 25 years. The gallery was a natural extension of their hobby when they retired.

They did what many collectors dream of — opened their own space determined to show the region’s finest artists, with occasional airings from their own collection.

They have such a show at the moment, called African Modern. From their personal gathering of around 400 paintings, drawings and sculptures they have selected just 34 paintings and nine sculptures to display until November 9.

Nothing is for sale and the show represents a cross section of the thoughts of two people whose sensitivities usually, but not always coincide. Hellmuth, for instance, edges towards conceptual and abstract art, while Erica has a more traditionally grounded taste.

DOWN MEMORY LANE

This show is a trip down memory lane, filled with excellent examples of the usual suspects: Jak Katarikawe (three woodcuts of flying birds from the 1980s), Wanyu Brush (a couple of rare watercolours), Annabelle Wanjiku (two big, bold paintings typically blue); Kivuthi Mbunu (no fewer than six meticulously coloured pencil drawings); Rosemary Karuga (six collages) and Zacharia Mbutha.

Then there are the surprises: Two stunning Tingatinga paintings on board — an elephant and a hyena — by E.S. Tingatinga himself, the man who founded the style and the school; a huge painting by George Lilanga; and without doubt the finest painting by Joel Osweggo I have ever seen. Called Refugees, it is of two men and a camel in a compelling triangular composition, painted directly and with authority in 1995, without the nervous, chalky palette that for me takes the edge off some of his work.

Two surprises were a painting of a waterfall by Patrick Kayako and a couple of disaster scenes by Samwe Magga from the 1998 embassy bombings — two painters who have unaccountably slipped from the public eye. The sculptures were by the Makonde carvers of Tanzania and Shona stone workers from Zimbabwe.

Go to the East African to read the full article.