Problem with Kenyan publishers

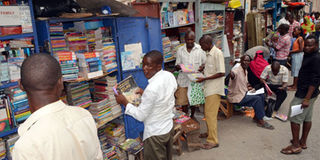

While Kenyan writers are busy churning out manuscripts every day, there is a serious bottleneck among the local publishers. PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

I am aware that publishing houses receive many unsolicited manuscripts monthly, but I fail to understand why, in this electronic age, it should take a year or more to respond to a submitted manuscript.

If you run a publishing house, surely someone should be employed to read manuscripts and say ‘aye’ or ‘maybe’ to a manuscript within three months (which, by the way, is the industry standard to manuscript response worldwide?).

I love reading much more than I love writing. I suspect if I did not like reading, I would not be a writer.

The well-written books inspire me to be a better writer. The badly written books teach me how not to write.

Kenyan publishers are, sadly, not doing much to ensure that other readers and I get more of the former and less of the latter.

Their inability to respond to submissions timeously; poor editing; unfavourable contracts; and poor marketing are but some of the problems beleaguering the publishing industry.

Response to Submissions

I am aware that publishing houses receive many unsolicited manuscripts monthly, but I fail to understand why, in this electronic age, it should take a year or more to respond to a submitted manuscript.

If you run a publishing house, surely someone should be employed to read manuscripts and say ‘aye’ or ‘maybe’ to a manuscript within three months (which, by the way, is the industry standard to manuscript response worldwide?).

If a nay, then someone knows and goes back to the drawing board. If ‘maybe’ then the publisher can send the manuscript to an independent committee of three (a literature lecturer, a literary critic, a published writer may be a possible team)and pay them a small amount each to send their recommendations and one-page readers’ reports to the publisher, who would then decide whether the work in question is something they would like to publish and how much work must be put in.

By far the most important work on a manuscript after it has been accepted for publication is editing.

Editing

I don’t care how brilliant a writer one is, no one can do without editing (as the sub-editor of this piece will prove). I fail to understand why, in one of Africa’s most literate nations, publishers have decided they cannot find good editors.

It is worrying when I pay Sh1,500 for a book and while reading, a character initially called Wambui becomes Wangui in the next chapter. And oversights where a book starts with a child being 12 and ends with the child still 12, but the mother of that child has had two more children and the book is not science fiction or magical realism.

Or a man leaves his pregnant girlfriend to go to another country and when he returns six years later the child is still three years old.

It’s disturbing that the most brilliant contemporary Kenyan literature has been edited beyond these borders.

Are publishers in this country truly saying there are no editors worth their salt with the red ink or are they unwilling to pay them enough to make it worth their while?

And if the manuscript is not well-edited but the writer claims fatigue or tries to rush to put it out, the publishing house reserves the right to refuse to publish.

Badly edited books seriously disrespect the market of readers that is there and do neither the writer nor the publishing house any favours.

Contracts

The standard Kenyan royalty fee is eight to 15 per cent. While not as high as some South African publishers who give as much as 22 per cent, or as low as some Nigerian publishers at six per cent minimum, this is a competitive fee on the continent.

That said, perhaps the royalty percentage would be even better if Kenyan publishers actually stuck to contractual obligations and paid on time.

Late last year I got an email from a Zambian writer friend who stays in England. I have permission to reproduce the email here so I do, without naming either her or her publisher.

“Hi Zuks, I hope all is well. I need your advice. In 2008_______ Publishers in Kenya published one of my children’s books.

They went quiet on me so this year I decided to chase for royalties and they are messing me about. After many excuses and apologies (‘we have a few cash-flow issues’), they have now stopped replying my e-mails. I e-mailed their MD the other day and even he didn’t reply. Any advice on what I should do? Have you ever been in a similar situation? Any news in Kenya about them?”

That’s no royalty fee whatsoever since she expected her first payment in 2009, more than five years ago.

And this is not a fly-by-night publisher but one respected on the market if their muscle in the Kenya Publishers Association and other such organisations is anything to go by.

And no. I didn’t hear anything about this publisher having cash-flow problems. If anything, they’ve been sounding out some events management companies I know to host some events to celebrate their many years ‘achievements.’

Think Kenya at 50 without the fireworks.

And this is not the only author I’ve heard complaining about lack of royalty payment. I know a writer whose book is a setbook and he is yet to receive any royalty payment since 2002.

Marketing

Then there’s the marketing. Publishers, it doesn’t cost as much as you think. There is Facebook, Twitter or Instagram to hype it all up. Then there are traditional book spaces.

Talk to bookstore owners. Find a free venue where the writer can discuss their book and have some copies on sale.

Talk to literature departments at universities so your author can do a seminar. And please eh my fellow Africans, let’s stop this ‘Nairobi si Kenya’ nonsense. There are bookstores and reading people all over the country.

And don’t say Kenyans don’t read either. In the last few years, I have done book readings in Nairobi, Kisumu, Eldoret, Kakamega and Embu.

In all these places, not only were the readings well attended but the books sold well. Kenyans do read. If they did not, Bookstop at Yaya Centre with its wide stock of African and world literature, would not exist.

Another problem with marketing is the hyping of unavailable books. Late last year, a friend from South Africa was in town and wanted a book that had won some prize as a Christmas present for his son.

Several attempts to get the book from the publisher produced negative results (think emails and phone calls from October until mid-December).

Now come on folks. If your author has won an award, doesn’t it go without saying that you’d slap a ‘winner of the Baobab/Mugumo/JK/ Burt Award” on the cover and market it like crazy in bookstores and online to ensure maximum sales? Publishers of Was Nyakiru My Father? I’m looking at you.

Perhaps the only salvation for the publishing industry is for Kenyan writers need to start looking beyond the borders.

An afternoon online will show publishing houses on the continent and beyond that will give feedback and publish unsolicited manuscripts.

Maybe this is the only way Kenyan publishers (if, indeed, they are interested in publishing anything beyond school textbooks, which they don’t seem to be), will wake up. Kenya is a major player on the continent.

Its publishing scene should be a reflection of this. So Kenyan publishers, as I’d say in Zezuru, “tipeiwo masiriyas tapota” (give us some seriousness, we beg). Kimathi did not die for this.

Disclaimer: I haven’t been published by any Kenyan publisher. I speak purely as an observer of the scene for the last three years.

I would be interested in a rebuttal from Kenyan publishers or Kenya Publishers Association if only so that writers are more informed of publishing policies and politics. All the examples cited above are however, true.

Zukiswa Warner is a South African author living in Kenya.