Kenyan top model Ajuma campaigns against skin lightening cosmetics

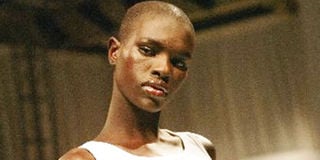

Kenyan model Ajuma Nasenyana walks the runway at the Ford Models' Super Model at the New York Public Library. Photo/FILE

As you leave Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA), you will be confronted by large billboards on which the models advertising products are either white or very light – none is dark-skinned.

The mass media seem to be saying that really black women are the opposite of the ideal.

Magazines, TV, radio and movies and the rising influence of Western pop culture are fervidly promoting a Eurocentric, blonde-haired, light-eyed and stick-thin standard of beauty.

And no one seems more peeved by this emerging trend than Kenya’s top model Ajuma Nasenyana.

“It seems that the world is conspiring in preaching that there is something wrong with Kenyan ladies’ kinky hair and dark skin,” says Ajuma, a woman with dark skin, short hair and high cheekbones, complains.

Big advertising and modelling agencies seem to be promoting the light-skinned over the dark-skinned model, she says, pointing to a Swedish cosmetics firm that recently entered the Kenyan market.

“Their leaflets are all about skin-lightening, and they seem to be doing good business in Kenya. It just shocks me. It’s not okay for a Caucasian to tell us to lighten our skin,” she says. She says Europeans have natural skin and wonders why they want “us to bleach ours”.

On a visit to Kenya, British supermodel Naomi Campbell, who has complained that she is rarely featured on the cover of British Vogue, raised concerns that black models were being sidelined by modelling agencies.

“It’s a pity that people don’t appreciate black beauty,” she said.

These days whenever she has the opportunity, Ajuma speaks out against skin-bleaching, and she is taking it on as her own fight.

Attitudes against colour and the increasing promotion of skin-lightening products are placing a burden on dark-skinned women.

Last year, Psychology Today published a blog by evolutionary psychologist Satoshi Kanazawa titled “A Look at the Hard Truths About Human Nature” that raised a firestorm by declaring that black women are objectively less attractive than white women but also less attractive than black men.

Physical attractiveness

“The only thing I can think of that might potentially explain the lower average level of physical attractiveness among black women is testosterone,” he wrote. “Africans on average have higher levels of testosterone than other races, and testosterone, being an androgen (male hormone), affects the physical attractiveness of men and women differently.

“Men with higher levels of testosterone have more masculine features and are, therefore, more physically attractive. In contrast, women with higher levels of testosterone also have more masculine features and are therefore less physically attractive. The race differences in the level of testosterone can therefore potentially explain why black women are less physically attractive than women of other races, while (net of intelligence) black men are more physically attractive than men of other races.”

Criticism forced Psychology Today to first change the blog’s title and later to retract it altogether.

In Kenya, many women use various cosmetic products apparently to make themselves more attractive. They straighten their hair because they do not like their natural curls.

Skin-bleaching products like Carol Light are now some of the fastest moving in Kenya.

Other bleaching creams, soaps, gels and lotions such as Movate, Jaribu, Peau Clair, Betalemon and Mekako, which have long been banned in Kenya because of their hydroquinone, steroid and mercury components, are still being used illegally.

The irony of all this is that while Kenyan women appear willing to do anything to make their skin appear lighter, Caucasians are spending as much time as possible under the sun lamp because they do not like looking too white.

Black women have faced all kinds of discrimination from various quarters.

When defending himself against sexual assault charges, African-American, Washington Redskins football player Albert Hayensworth said he couldn’t have groped the breast of an African-American waitress.

“She is a little black girl who’s just upset I have a white girlfriend. I couldn’t tell you the last time I dated a black girl. I don’t even like black girls,” he said.

Fashion capitals

Very few black models have managed to rise to international stardom. The 28-year-old Ajuma is one of the members of this very small club.

She is a familiar face on the runways of Milan, Paris, London and New York, the fashion capitals of the world.

She has been a model for top clients of Ford Models like Vivianne Westwood and Alexander McQueen.

She has been on runways for Victoria’s Secret, Alexis Mabille and Martin Grant. And she had a cameo appearance in the first Sex and the City movie.

Last October she was crowned Model of the Year at the Africa Fashion Week in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Yet the 5-foot, 10-inch dark-skinned beauty with pillow lips and short, natural hair who uses the same soap for her face and legs and then oils her body with Vaseline and cocoa butter lotion, has never bleached her skin to be famous.

“I have never attempted to change my skin. I am natural. People in Europe and America love my dark skin. But here in Kenya, in my home country, some consider it not attractive,” she says with a tinge of disgust in her voice.

Ajuma grew up in the time of the Face of Africa (FoA) model search when the event had one of its greatest boosts after its very first black model, Oluchi Onweagba, went on to become a superstar.

Ajuma was the first black model to make it as close to winning the Ford Models competition in New York where she competed against over 50 contestants.

But like a number of dark-skinned models, Ajuma has faced her own challenges.

Despite being the crowd favourite at the Miss Tourism Kenya competition in 2003, she failed to win the title. Some people said it was because of her dark skin.

During the 2003 New York Fashion Week, Ajuma participated alongside black models Naomi Campbell and South Sudanese Alek Wek for designers like Baby Phat and Carlos Mienes.

Other black models have also faced overt racism. In the 1970s, despite being a middle-class multilingual university student, Iman, the first black supermodel, was pitched as an illiterate Somali goatherd.

Internationally, black models make up just four per cent of all full-time working models.

A 2008 survey of models in New York Fashion Week found that six per cent were black, six per cent Asian, one per cent Latina and a whopping 87 per cent were white. Some fashion labels like Calvin Klein label used only white models.

Even those who got a chance to participate in the event were said to be black models with very unique features like a very skinny nose and very angular faces.

“When you flip through fashion magazines like Vogue and only see white models, then you get the feeling on what is happening to black models. It is not fair,” Ajuma says.

Skin of Beyonce

In 2008, make-up giant L’Oreal was accused of lightening the skin of Beyonce in its advertisements. The company denied the claims.

A year later, Elle magazine was also accused of lightening the skin of Precious actress Gabourey Sidibe. Elle told media that they had done nothing out of the ordinary.

In 2010 Jamaican dancehall star Vybz Kartel was criticised for lightening his skin.

He defended himself saying, “I feel comfortable with black people lightening their skin. It’s tantamount to white people getting a suntan.”

He went on to launch his own line of skin-brightening products.

But Ajuma’s new campaign is grabbing attention, and the fight against discrimination in the modelling industry is gathering momentum.

On numerous platforms around the world, campaigns pushing for black models to be recognised in the same way as their white counterparts are gaining momentum.

On more than one occasion, black models Tyra Banks and Iman have raised the issue, arguing that the industry is discriminating against black models, in some instances at levels worse than in the 1960s.

At some events, designers are said to have openly told black models that they are not welcome at lot castings.

In America, aspiring black models have their lobby fighting against such discrimination. Ajuma says black models have been forced to accept the humiliation.

“But things should not be that way,” she says.

Months ago Vogue Italia featured a bevy of black models in what they called a “Black Allure” spread.

They included Ajak Deng, Chanel Iman, Arlenis Sosa Pena, Jourdan Dunn, Melodie Monrose, Lais Ribeiro, Rose Cordero, Mia Aminata Niaria, Sessilee Lopez, Joan Smalls and Georgie Baddiel dressed in the latest Versace, Ferragamo, Louis Vuitton, Lanvin and Dior designs.

The US film industry has also begun to fight the discrimination. A good example is the documentary The Colour of Beauty based on the story of Renee Thompson, who is trying to make it as a top fashion model in New York.

She has the looks, the walk and the drive, but she is a black model in a world where white women represent the standard of beauty.

Some designers claim that the bodies of black models make their clothes look too sexy, and hence they prefer the thinner white models.

Modelling agencies

Preference for the thin whites turned away many models, including Ajuma, but some modelling agencies objected because about 30 per cent of their models were on the verge of being left jobless.

The thin-models call was marred by a whirlwind of controversy after the death of a British model who had succumbed to eating disorder related complications.

Ajuma was born in January 1984 in Lodwar where her family still stays. In 2003, she was crowned Miss Tourism Kenya Nairobi.

The year heralded better times for the Lodwar girl. During the Miss Tourism competition, Lyndsey McIntyre of Surazuri Modelling Agency was impressed with her.

Her stories have been written and photos appeared in several magazines and videos.

Ajuma wants to start an all-natural line of cosmetics for women of “ethnic” or dark looks in the hope that the products might keep skin-bleaching cosmetics at bay.