First parents’ meeting ends in disarray over lunch fee

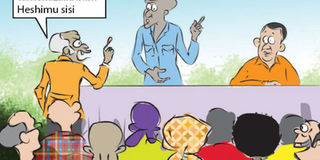

“This is a very good programme Bwana Dean,” said El Nino. “But I doubt it can work here. The parents here ni mkono birika, very mean.” Electina supported him. ILLUSTRATION| JOHN NYAGAH

What you need to know:

“This is a very good programme Bwana Dean,” said El Nino. “But I doubt it can work here. The parents here ni mkono birika, very mean.” Electina supported him.

“Why don’t we make it simple and just provide mahenjera?” she asked.

I told them my experience with mahenjera elsewhere. “First of all some pupils did not like it and started going home to get better lunch which defeated the purpose of the whole programme,” I said.

“Furthermore when we asked the parents to bring the foodstuff, some brought spoilt maize or beans which led to food poisoning.”

A few days after I reported at Daraja Mbili Primary School, I called the PTA chairman, Bwana Tocla, for a meeting. For those who do not know, Tocla is my brother-in-law, as he is the “big” brother to Fiolina, the lucky laugh of my enviable life.

We discussed a couple of matters that would help to move the school forward, although I noticed he was only keen on matters that could lead to his financial gain.

One of the things that interested him most was the lunch programme for Standard Six and Seven that I suggested. It is a programme that had worked in other schools and which I now wanted to introduce at Daraja Mbili but to be slightly different from what other schools had.

“So that they can read well and start preparing for KCPE early, Class Six and Seven will not go home at lunch time but we will prepare lunch for them at school,” I told him.

“How?” he asked me. I told him that parents would have to raise the food needed either by contributing food or money. I explained that I had seen programme done in other schools and knew what could work or could not.

“Parents should bring maize and beans so we cook mahenjera for the students,” I said. “But if we go the mahenjera way, the money they will give is very little as we will only need something small to pay the cook and buy salt.”

This did not look attractive to Tocla, and he asked me if there was another option where parents could contribute money. I told him that we could do fried beans and rice for two days every week, ndengu rice another two days and beef rice once every week. This impressed Tocla and he asked me to work out how much was needed per student.

I called Electina to work out on the cost. Although she was pessimistic, she reverted to me with the needed figures. Every Standard Seven and Six student would need to contribute Sh1,250 per term if the highly balanced diet, lunch study programme was to take off. I discussed this with the teachers.

“This is a very good programme Bwana Dean,” said El Nino. “But I doubt it can work here. The parents here ni mkono birika, very mean.” Electina supported him.

“Why don’t we make it simple and just provide mahenjera?” she asked.

I told them my experience with mahenjera elsewhere. “First of all some pupils did not like it and started going home to get better lunch which defeated the purpose of the whole programme,” I said. “Furthermore when we asked the parents to bring the

foodstuff, some brought spoilt maize or beans which led to food poisoning.”

BROKE PARENTS

“Bwana Dean if you can convince the parents on this project that will be good,” said Fred, who had only appeared that week. “Maybe we are thinking these parents are broke na wako na pesa.”

“I agree,” added Electina. “Let us call for a parents’ meeting and sell the idea to the parents.” That evening, at Hitler’s, I met Tocla. After I had bought him a pick up or two, I asked him if we could call the concerned parents to discuss the lunch programme.

“We should call all parents to come know you,” he said. “Mr Sande rarely called for a parents meeting so I am sure lots of parents will come.”

He told me that once we agreed on a date, he will help me to mobilise the parents. We settled on last Wednesday; and a little more than a week ago, we asked all the pupils to come with their parents on that day. Using his own village networks, Tocla also

talked to most parents.

Come last Wednesday, I called for parade at 9am and released all the pupils to go home. Each was to leave their belongings at school and they would only be allowed back to school if they returned with their parents. At 10.30am, a good number of parents

had arrived. Just like in Mwisho wa Lami, most of the parents were old, a clear indication that these were mostly the grandparents to the students.

MY SUCCESSES

We started the meeting with introductions. Tocla stood and thanked Dr Matiang’i for posting me to Daraja Mbili. He read out some of the successes I had achieved at Mwisho wa Lami and hoped that I would replicate the same at Daraja Mbili.

“Haiya tusimame tukaribishe Dre na makofi ya kilo. Moja… Mbili…”

I thanked the parents for such a warm welcome, without mentioning the week Tocla locked me out of my office, I assured the parents that I will be taking Daraja Mbili to the next level. No-one knew what this next level was, myself included.

I then introduced the lunch programme agenda, clearly explaining how it would work and its benefits to the pupils and parents. I invited Tocla who also supported the idea, and urged all the parents to support it by paying the Sh1,250 per student.

“In fact this should include even Class Five students,” he said. Some parents cheered him.

We decided to listen to feedback from parents.

“Thank you my son-in-law for coming to this school to help the people of my daughter who you live with,” started one of the old men whom I later learnt was called Philemona.

“The only problem my son is this Sh1,250 you want us to pay. My son does not even send me that amount for all his children so where do you want me to find the money.”

“We know you have not finished paying mahari ya Fiolina usianze kutuitisha tukuchangie mahari,” he added before sitting down.

Next was Senje Albina. She had been a member of the PTA but I was made to understand that she had been dropped. She was never happy with the idea of being dropped as she had always taken it as a fulltime job. Based on my history with her, I did not need a calculator to know that she would oppose the programme.

“I like the lunch programme so that our children can pass exams well,” she started positively.

“My only problem is who will give food and water to the cattle at lunchtime?” she asked. “Theophilus does not just come for lunch to eat, he also has some work to do, who will be doing it if he remains at school?”

Most parents supported her on this, including Philemona.

Tocla and I tried to cool them down, and to explain the programme further, unsuccessfully.

“Philemona, please listen,” I started.

“How did you call me?” Mzee Philemona asked me. “You have married my daughter and you are calling me by name as if I was circumcised on the same day with you? You don’t know I am your father-in-law?” he asked. “You should respect me.”

“Hawa watoto wa siku hizi hawana heshima,” said another old man as the murmuring went up, making it difficult to proceed with the programme.

“Wazazi tafadhali nyamazeni,” I said meekly.

“Andrea kumbuka sisi hapana wazazi wa hii shule,” Philemona said. “Sisi ni wazazi wako, tumekuzalia bibi heshimu sisi.” There were loud jeers as Philemona said this.

Upon further consultations with Tocla, the PTA chairman, we tried to discuss another topic but it was difficult as the parents did not keep quiet. As such, we closed the meeting without any agreement.

Late that evening, at Hitler’s, Tocla asked me to give him two weeks to convince some parents on the programme. Since he knows he will get something out it, I am trusting on him to make it happen.