The art of celebrating African womanhood

Bertier's painting of Wangari Maathai. PHOTO | JOHN FOX

What you need to know:

- The particular painting I am talking about — a very big painting, by the way — is hanging in an exhibition called “Celebrating Women in Art”. Bertier calls it “Wangari Maathai, a Lady of Commitment”.

- It is his tribute to the life of the late environmentalist, activist and writer. It is the centerpiece of an exhibition in celebration of women — an exhibition at the museum that will run to the end of this month.

They call it a masterpiece. Well, I don’t know enough about art to call any work a masterpiece. But Bertier’s painting, now on show at the National Museum in Nairobi, is well worth a good look.

I’m a great fan of Bertier — of his paintings and metal sculptures. His real name is Joseph Mbatia. I once asked him why he adopted a European name.

“I did it because people don’t take African artists seriously,” he said. I don’t know about that. But I do know that many people take Mbatia/Bertier seriously because he doesn’t seem to take himself all that seriously. His works are full of humour. He can poke fun at grasping politicians and lascivious priests — and that, then, is also very serious stuff.

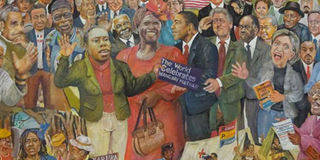

The particular painting I am talking about — a very big painting, by the way — is hanging in an exhibition called “Celebrating Women in Art”. Bertier calls it “Wangari Maathai, a Lady of Commitment”. It is his tribute to the life of the late environmentalist, activist and writer. It is the centerpiece of an exhibition in celebration of women — an exhibition at the museum that will run to the end of this month.

It is a very busy painting; busy with the things Wangari Maathai was committed to: leading her Green Belt Movement, planting trees with youngsters, demonstrating against land-grabbing in Karura Forest — for which she was beaten up.

FUN PAINTINGS

She is, of course, seen receiving her Noble Peace Prize. And the painting is crammed with people honouring her. Obama is there. So are Bill and Hillary Clinton. George Bush. Nelson Mandela. Archbishop Tutu. Even the British Queen is there. And many, many more. It’s rather like looking at a “Where’s Wally?” illustration, looking for anyone you think should be there.

Also, Bertier can’t put aside his raunchiness. There are a few women with bared breasts; some as a sign of protest; some, it seems, just for the hell of it. Masterpiece? I don’t know. But it’s a fascinating painting — and full of fun.

There are a good number of other works by other painters on display — and some very good ones, too. There are a couple of Cubist-style paintings by Paul Kintu: colourful, angular and enigmatic. “Either Way”, one of them is called. Which way? I am still trying to work it out.

Patrick Adonyo’s “Village Woman” is not at all enigmatic. Wearing a green dress, tall and proud, with a half-smile, she is balancing a basket of mangoes on her head, and she is leading other women to the market.

Then there is the exuberance of Arthur Patrick’s dancer, with arms raised and shoulders bared; the more delicate beauty of Gilbert Ouma’s “Lady on the Shore”; the brown and naked dancing figures with elephants and fish in the two Tinga-Tinga-like paintings by Damba Ismail.

Just outside the exhibition room, and in the corridor leading back to the main galleries, there is metal sculpture by another favourite artist of mine — Kioko Mwitiki. It is a Maasai-like figure, draped in a metal robe decorated with spark plugs. Kioko calls it “An African Woman”.

All this celebration of African womanhood took me back to the debates we used to have about the Négritude movement back in the 1960s with my students at the University of Adult Studies Centre in Kikuyu.

We talked about the Ambi advert in the newspapers those days. It showed a young and light-skinned executive saying goodbye to a light-skinned flight attendant as he was about to step down from his executive jet — and the guys putting the chocks under the wheels were dark skinned.

And I thought again about the writings we used to study: works by Négritude writers such as Aimé Césaire, Léopold Senghor, and Léon Damas...

After the exhibition I went into the excellent museum shop. I found a reprint of a collection of poetry I used to have but most probably have lent and lost: “Poems from East Africa”, edited by David Cook and David Rubadiri. I bought it and took it to read over a coffee in the museum’s café.

CRACKED MIRROR

But it was not until I got home that I found what I was really looking for: some lines from “Song of Ocol” by my old colleague and friend, Okot p’Bitek:

“Ah!

Come,

Walk with me

In the City gardens,

Hold my hand...

My woman

Here’s a rose bud,

Keep it,

Guard it,

Don’t lose it,

Do you hear?”

If he could have seen it, Okot would have relished this “Celebrating Women” exhibition. He would also have understood what Wangari Maathai meant when she wrote in her The Challenge for Africa that Africans have too often looked at themselves as if in a cracked mirror — another person’s mirror, whether a colonial administrator or a missionary — and seen only a distorted image.