Return to Mashatu, the land of giants

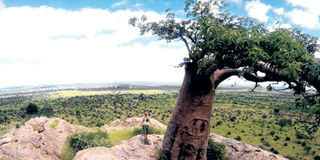

Mashatu is named after a local species of tree, but it also bears the name, ‘The Land of Giants’, because of the elephants and enormous Baobab trees that abound in the region. PHOTO| ANDREAS FOX

What you need to know:

The Bantu were agriculturalist, and they brought grains and cattle and readily traded ivory, shells and metals with coastal communities.

Eventually, later communities had their royalty move up onto the flat-topped ridges in the area.

You can still see signs of the original village sites where topsoil was carried up and rock walls were formed as a means of defence.

Ever since my mother and I drove through Botswana in 2013, I have been keen to go back. We had explored the salt flats, the Okavango and Chobe, and we were continually struck by the country’s beauty — however flat it was.

Now, I have just returned from some time in the totally contrasting Tuli Block, known as Botswana’s ‘hardveld’, for its dramatic, rocky landscape. Situated in a remote corner of the Mashatu Game Reserve, our camp overlooked the ancient Motloutse River, which is a focal point for many of the region’s thirsty elephants.

The reserve is part of the greater Northern Tuli Game Reserve, in the eastern-most corner of the country. Bordering South Africa and Zimbabwe, it boasts one of Africa’s largest unfenced tracts of privately owned conservation land.

Mashatu is named after a local species of tree, but it also bears the name, ‘The Land of Giants’, because of the elephants and enormous Baobab trees that abound in the region.

Unfortunately, rhinos can no longer be found there, since they were poached and hunted out over the 20th Century.

But lions are free to roam and individuals readily cross out of the protected areas and even across the borders.

There are also large resident populations of leopards, spotted and brown hyenas, as well as cheetahs and wild dogs.

Aside from the prolific wildlife, the area has a fascinating geological and human history. Huge sandstone ridges, raised up by underlying molten rock, make for a jagged topography.

Where lava spilled out onto the surface, basaltic soils give rise to swathes of mopane scrublands. The easily weathered sandstone bears the scars of thousands of years of animal and human passage, connecting the river and feeding grounds.

The hunter-gather Khoisan bushmen were the first humans here. While certain communities still live in the Kalahari and Okavango, it is believed the Tuli bushmen were pushed out, or integrated into, the Bantu communities that started arriving around 700 AD. Bushman relics, including rock art sites and stone tools, can still be found.

The Bantu were agriculturalist, and they brought grains and cattle and readily traded ivory, shells and metals with coastal communities.

Eventually, later communities had their royalty move up onto the flat-topped ridges in the area.

You can still see signs of the original village sites where topsoil was carried up and rock walls were formed as a means of defence.

Today, you often come across pottery and beads, but some of these sites remain sacred, and only with the President’s permission can you climb there.

This was part of the 1,000-year-old Great Mapungubwe Kingdom, a precursor to Great Zimbabwe. The Mapungubwe National Park, on the other side of the Limpopo River in South Africa, is well worth a visit, featuring an excellent information centre and the chance to climb and explore the archaeological wonders of Mapungubwe Hill.

Botswana eventually became a British Protectorate in 1885. Bechuanaland, as it was known then, was considered to be under threat from Boer encroachment.

During the Anglo-Boer war, some of the local sandstone ridges were used as gun stations to fire shells across the Limpopo River into Boer territory. You can still see some foundations, spent artillery shells, and thick-glassed medicine bottles from the era. Around 1893, Cecil Rhodes famously negotiated with the local chief to let him use the Tuli Block for a section of his Cape-to-Cairo railway. The contract was ‘signed’ by all parties when they carved their initials into a Baobab tree that still stands on yet another of these ridges.

Colloquially called ‘Rhodes’ Baobab’, you can visit the site and just make out the inscriptions.

The early 20th century saw farmers attempt to grow more crops and graze larger herds of cattle. However, just as Rhodes found the area too difficult for his railway, the farmers eventually gave up and, after independence in 1966, the region turned to wildlife conservation and tourism.

There are many lodges in the Tuli Block, the most notable being the Mashatu Lodges, as well as Tuli Safari Lodge and specialist operations such as Limpopo Valley Horse Safaris and Cycle Mashatu. All are easily accessible within a half day’s drive from Johannesburg or by a charter flight.

The area is fascinating to explore and it offers great game viewing, human history, and stunning vistas from atop the ridges. It’s ideal for walking safaris. For more about the pleasures of a walking safari — there will have to be another article.

The writer is an associate consultant of iDC