The tragedy of being a book reviewer in Kenya

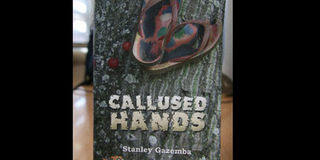

The tale of Callused Hands replays the classical violence of socio-economic inequalities. Gazemba’s is a story of the trials and tribulations of farmhands. The books is just plain too difficult to read. PHOTO/NATION

What you need to know:

- Why? First, because review copies are hard to get, especially new books. In many cases they are just unaffordable. Imagine buying a book at Sh4,500, reviewing it and being paid Sh3,000 for the trouble.

- Kenyan publishers and authors often just don’t put in enough effort to prepare their books. From outrageously designed cover pages to irritating blurbs and pretty avoidable mistakes, some books published in Kenya are quite poor jobs.

- The tales of Callused Hands and Den of Inequities replay the classical violence of socio-economic inequalities. Gazemba’s is a story of the trials and tribulations of farmhands. Kombani’s is a narrative of the tragedy of life of squalor, deprivation and risk in the poor neighbourhoods of Nairobi. But both books are just plain too difficult to read.

It is not an easy task to review books in Kenya. And it is not even rewarding.

Just like the African writer complains about not being able to pay bills from writing, a book reviewer isn’t likely to be paid enough to buy the books to review.

And should you get the book from the publisher you will be expected to review it and publish the write-up promptly, even though publishing is your editor’s prerogative. The point I wish to make is that being a book reviewer in Kenya is often really a tragic job.

No copies to review

Why? First, because review copies are hard to get, especially new books. In many cases they are just unaffordable. Imagine buying a book at Sh4,500, reviewing it and being paid Sh3,000 for the trouble.

This happens all the time to reviewers; it also partly explains why you continue to see reviews of Things Fall Apart and many of those ancient African Writers Series books that are easily available.

Or the publishers won’t just send you a review copy. It is a practice in many other parts of the world that publishers send free copies to reviewers. And this happens without any expectation that the reviewer is obliged to review the copy.

Poor workmanship

Second, often a reviewer in Kenya will get the copy of the book to be reviewed way after the launch. What’s the point of reviewing a book that has already been launched?

What good is the publisher, the reviewer and the media outlet that carries such a review doing for the author if they can’t whet readers’ appetite in advance of the book being on the shelves?

Third, some Kenyan publishers and authors often just don’t put in enough effort to prepare their books. From outrageously designed cover pages to irritating blurbs and pretty avoidable mistakes, some books published in Kenya are quite poor jobs.

I just recently finished reading two quite interesting books: Stanley Gazemba’s Callused Hands and Kinyanjui Kombani’s Den of Inequities – books fresh from the press.

I know both writers; they are the future of Kenyan literature. They are committed individuals, struggling with day jobs and probably only writing in the dead of the night. Their previous books, The Stonehills of Maragoli and The Last Villains of Molo respectively, are definitive novels about life in rural Kenya and the so-called inter-ethnic violence.

The tales of Callused Hands and Den of Inequities replay the classical violence of socio-economic inequalities. Gazemba’s is a story of the trials and tribulations of farmhands. Kombani’s is a narrative of the tragedy of life of squalor, deprivation and risk in the poor neighbourhoods of Nairobi.

Difficult to read

Both stories are deeply poignant; they will punch any reader conscious of the pitiful inequality in Kenya right in the pit of the stomach. They are parables of how Kenya has developed only for those who have historically been able to accumulate wealth by all means crooked. But both books are just plain too difficult to read.

These two books are afflicted by grammatical, spelling and punctuation mistakes. How difficult is it for an editor to, for example, find out if ‘horde’ and ‘hoard’ are synonyms or not?

The books are victims of how pervasive stereotypes have become part of everyday language in Kenya – why would someone like Kombani whose stories are about ethnic insensitivity in this country refer to a character as ‘the Somali policeman’?

Glaring errors

These books are afflicted with such basic problems like confusion of character names – one moment a character is X, the next he is Y. Even the title Den of Inequities leaves one wondering if it was meant to be ‘Den of Iniquities’, as is suggested in the rest of the book and as the allusion to the biblical ‘den of robbers’ comes to mind after reading the story.

In other words, if you are a critic, what are you supposed to say about such sloppiness on the part of publishers, and the author who ‘signed off’ the copy pre-printing? Wring your hands, say a few good words and ‘understand’ that this is Africa, that English is a foreign language and that these are just a few minor mistakes that will be weeded out in the next print?

No, these are very irritating mistakes, especially if the text appears to be ‘designed’ to end in a certain fashion, as both Callused Hands and Den of Inequities are.

The first book ends in a very NGOist manner. A lawyer doing pro bono work on behalf of the exploited workers supposedly wins a case against the owner of the farm, gaining compensation for the central character of the tale, a widow.

Twists in the tales

This ‘happy’ ending is just too plain unconvincing considering that this is Kenya we are talking about! The second book has a twist in the tale that is just too contrived.

Part of the story of Den of Inequities is that of the extra-judicial killings in Kenya in the past.

In this story, Kombani suggests that the killing of policemen by the Chama (thinly disguised reference to Mungiki), which triggers police killing of suspected members of the Chama is mistaken, and that the police were really killed by a revenge-seeking young man who lost his wife and child to another man after being jailed — even though he didn’t commit any crime.

This is an interesting suggestion, absolutely original. But it just falls short of convincing because there is hardly development of the rage that drives the character, Omosh, to murder policemen. In other words, Omosh’s actions aren’t ‘motivated’ enough; and so the plot of the text fails the reader here.

Fourth, following on the issues I raise about the two books above, the other tragedy of the Kenyan critic is to be expected to work using local standards. Fine, I am not necessarily a believer in universal, world or gold standards. I am happy to do my literary transactions in copper currency.

Readability test

But once the book is on the shelves, I think it should be judged and charged by some bare minimum and acceptable standards.

Many Kenyan books just fail the readability test, which is the entry standard. So, when some Kenyan ‘critics’ start insinuating that a critic is too hard on local books, then why would they, at the same time, complain that our literature hardly registers globally?

Lastly, Kenyan authors and their publishers forget too easily that their products end up in the classroom, in homes and all over the world, and are therefore an important part of our cultural capital and heritage.

The critic is a midwife in that set up. The critic is a maker, protector and conserver of literary and cultural taste. She or he is the guinea-pig of literary production. Surely, what is bad for the critic usually can’t be good for the public! The critic isn’t the enemy of the author.

The critic is a co-creator, even if of the vulture-kind.

Therefore, the kinds of insinuations that one reads about Kenyan critics on social media and sometimes in the ‘letters to the editor’ pages, suggesting that most Kenyan critics do not read, have exaggerated standards or are not qualified to comment on certain subjects don’t serve the writers’ and publishers’ world much.