This is what post-poll violence did to us – Kiambaa survivors

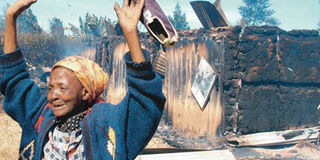

Elizabeth Kimunya wails at the sight of the burnt church where 35 people died on January 1, 2008. PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Survivors of the attack said that the irate youth herded people, mostly women and children, into the church, splashed petrol on it and set it ablaze.

- Some of the attackers claimed that a cooking stove that was inside the church was knocked down during the melee and started the fire.

- What is not in dispute, however, is that by the end of the attack, 35 people, among them 20 children, had been killed, including an elderly disabled woman whose remains were found near her wheelchair. It was this horror scene that Ms Kimunya was confronting.

- Her adopted son, Philip, aged 15 at the time, was in the church and suffered burns to his legs and hands. “I covered my face with my hands and groped around the church trying to find the door or the window,” Philip told Lifestyle this week.

- He felt the edge of the window and jumped out to safety.

The picture told the horror of it all: hands raised high in the air above her head in half-prayer, half-surrender, a torn shoe in her left hand, tears streaming down her cheeks as the charred iron sheets of what was her local church lay desolately all around her.

Elizabeth Irungu Kimunya, 70, was confronting a scene straight from hell – the burning of 35 people to death on January 1, 2008 at the Kenya Assemblies of God Church in Kiambaa village on the outskirts of Eldoret town.

It was the second day of an orgy of violence, death and destruction that was set off by the disputed results of the presidential elections of December 27, 2007. Half of the country had erupted in mayhem with the epicentre of it all being in Eldoret.

Ms Kimunya’s heart-wrenching picture, which was widely used by international newspapers, among them The New York Times, brought to the international community the horrors of Kenya’s violence, sparking a flurry of efforts to save the country from slipping into an imminent civil war.

Philip Kimunya and his mother Elizabeth at their home in Kiambaa home on Friday. They both narrowly escaped death on January 1, 2008. PHOTO| JARED NYATAYA

On the evening of December 30, Samuel Kivuitu, the chairman of the Electoral Commission of Kenya, announced the incumbent, President Mwai Kibaki of the Party of National Unity, as the winner.

Perceived supporters of his main rival, Mr Raila Odinga of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), citing massive fraud, would later be involved in tit-for-tat attacks with supposed supporters of Mr Kibaki, who had been hastily sworn-in at dusk in State House, Nairobi, just after being declared victorious.

The orgy of violence that lasted for nearly a month saw those thought to be supporters of President Kibaki carry out revenge attacks on Mr Odinga’s supporters in Naivasha and Nakuru. The mayhem stopped following a political deal brokered by former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan.

When the mayhem started, Ms Kimunya and her son, Philip, like so many residents of Kiambaa Village in Uasin Gishu, who were perceived to be supporters of Mr Kibaki, gathered at the Kenya Assemblies of God Church, which they believed was safe from rampaging youths.

But she, and an estimated 200 other residents of the village, discovered that the church provided little cover when the marauding youths stormed. The circumstances in which it got burned are a subject of dispute to date.

Survivors of the attack said that the irate youth herded people, mostly women and children, into the church, splashed petrol on it and set it ablaze. Some of the attackers claimed that a cooking stove that was inside the church was knocked down during the melee and started the fire.

What is not in dispute, however, is that by the end of the attack, 35 people, among them 20 children, had been killed, including an elderly disabled woman whose remains were found near her wheelchair. It was this horror scene that Ms Kimunya was confronting.

Philip and his wife Faith Cherotich at home in Kiambaa. PHOTO| JARED NYATAYA

Her adopted son, Philip, aged 15 at the time, was in the church and suffered burns to his legs and hands. “I covered my face with my hands and groped around the church trying to find the door or the window,” Philip told Lifestyle this week. He felt the edge of the window and jumped out to safety.

BARELY ESCAPED THE ATTACK

At the time, his mother told the Lifestyle that she barely escaped the attack when she went to answer a call of nature just before the attack occurred. But the incident has traumatised her so much that she developed mental illness and can no longer narrate the horrors of that day.

“My mother does not remember anything about the attack,” said Philip. “She was traumatised so badly and has never recovered. She was old by the time of the attack, but she was vibrant and her faculties were still good. But today you can never have an intelligent conversation with her. Once in a while she remembers her house which got burned during the violence, but that is all,” he said.

Ms Kimunya’s new national identity card which she was issued with after the violence indicates that she is 71 years old, but Philip said that her old ID card indicated that she was born in 1936 – 10 years older. “She could not even remember her age,” he said.

Philip stayed in hospital for four months and was looking forward to proceeding with his high school education. He had sat his Kenya Certificate of Primary Education examination in 2007 and scored 248 marks.

ONLY PERSON IN HER LIFE

He was admitted to Oasis High School, not far from home, but could not continue with his education due to his mother’s condition. “I am the only person she has in her life and I couldn’t just leave her at home without anyone to care for her,” he said.

Their house was completely destroyed during the clashes and the government, through the ministry of Special Programmes, in conjunction with the Danish Refugee Council, built her a simple mud house. A Good Samaritan dug a new well for them.

“That’s the only support we ever got. It is little but we appreciate because we don’t sleep out in the cold,” said Philip. “My mother was never a beggar and I was not about to start, so I accepted what fate served me and moved on with life.”

The violence claimed more than 1,000 lives and displaced more than 600,000, destroyed property worth billions of shillings and led to the formation of a Grand Coalition government between President Kibaki and Mr Odinga who would serve as prime minister.

WIDE ARRAY OF REFORMS

In the wake of the violence, a wide array of reforms were instituted to disperse the powers of the all-powerful Executive and ensure equitable sharing of the national cake. A Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission was formed with the aim of confronting Kenya’s historical injustices.

The passing in August 2010 of a new Constitution was the culmination of these efforts. The Constitution created a host of institutions independent from the Executive that were meant to serve Kenyans in an impartial manner.

Historical conflicts over land were identified by the Commission of Inquiry into the Post-Election Violence as a trigger to violence. One of the key institutions that the Constitution created to address this issue was the National Land Commission.

Philip shows the scars from the church fire. PHOTO| JARED NYATAYA

However, there is much debate about whether these institutions have delivered on their mandates. “Some have performed well, but to date I don’t understand the work of the land commission,” said Mr Ken Wafula, the executive director of Centre for Human Rights and Democracy in Eldoret.

He added: “The land commission has not done much to address the land injustices so far. I expected it to have set up offices specifically to deal with this issue in counties with the history of land clashes such as Uasin Gishu, Narok, Trans Nzoia, among others.”

In 2008, leaders from both sides of the political divide held hands in public and promised that not again would Kenyans go to war because of political competition.

Five years later, in 2013, two communities that were on the opposite ends of the conflict – the Kikuyu and the Kalenjin – formed an unlikely political alliance that propelled their political kingpins, Mr Uhuru Kenyatta and Mr William Ruto, to State House.

But as Kenyans prepare to go to the polls in August, echoes of the ethnic animosities in some parts of the country and disputes over the electoral process are being witnessed again.

“We have set this country on the path of violence with the kind of ethnic mobilisation that is going on now. People now know that there is no justice in Kenya or abroad. Victims of previous violence will likely arm themselves in advance,” said Mr Wafula.

TERMED IT PROPAGANDA

This week, Kenyans expressed outrage at a purported recording of Leader of Majority in the National Assembly Aden Duale, who is also the Garissa Township MP, urging youth to evict those deemed to be “outsiders”. Police are investigating but Mr Duale has in the meantime questioned the authenticity of the recording and termed it propaganda.

But it is such kind of incitement and political intolerance that led to the violence almost 10 years ago. Tension has also been witnessed in areas bordering the strongholds of Jubilee and the opposition Cord.

Furthermore, there is much acrimony in the National Assembly and the Senate where Jubilee MPs and Senators bulldozed through amendments to the Elections Act which the Opposition says are meant to steal votes.

No one was ever convicted for the attack on the Kiambaa church and some victims of the attack feel that this has prevented them from finding closure. Mr Joseph Githuku, a father of 10, who lost his wife Edith Mumbi and their son Samwel Irungu, is one of them.

“I persevere being a Kenyan; I am not proud to be a Kenyan because I would have been proud if justice had been done to me and to my wife and young son,” he said.

He added that he voted for Jubilee during the last elections but is thinking of voting for a different candidate this year.

“I don’t see what that vote has brought me. I expected justice from this government but I got none. I expected some sort of compensation for my losses but none has come. I am contemplating voting in a different person to see if there will be a difference,” he said.

The International Criminal Court at The Hague, Netherlands, dropped the cases against President Kenyatta, his Deputy and four others in 2014 and 2016 respectively, for their alleged roles in the violence. Journalist Joshua Sang’s case was dropped at the same time as the DP’s.

WITNESS TAMPERING

The court said that there was extensive witness tampering in both cases that it was impossible to prosecute the case impartially. Others who had been initially indicted over the violence are former Head of Public Service Francis Muthaura, former Commissioner of Police Maj-Gen (rtd) Hussein Ali and former Cabinet Minister Henry Kosgey.

Philip said that the lack of justice for the victims of the violence does not bother him so much. “My worry is that if we had pursued justice in that environment, it would have led to more clashes and bloodshed. I am at peace with myself,” he said.

On January 1, last year, Philip married Faith Cherotich from Mogotio, a true reflection of how far the hand of time has turned from that time almost 10 years ago when their communities hated each other so much.

“I met and married a beautiful person,” said Ms Cherotich. “I did not look at his tribe and whether our communities had fought. He is hardworking and honest and that is what attracted me to him.” The couple has a one-year old son.

Kiambaa is peaceful and calm today. But more than half of the houses are empty having been deserted by their owners who vowed never to return.

“I know people who just cry when you mention the name Kiambaa to them,” said Mr George Kairuri.

His father, Joseph Mwangi, lost his right arm during the church attack. A metal that had been inserted inside his arm reacted and poisoned his blood and he died in April 2015.

“For a moment, I contemplated leaving this place, too, but I was born here and my life is here,” said Mr Kairuri, a boda boda rider.

He added: “We now have peace. I go everywhere I want with my motorcycle and I see no reason to leave.”

Pastor Stephen Mburu, who used to minister at the Kiambaa church, but who has since moved to Huruma Estate in Eldoret, said he hoped that the grim lessons of the violence almost a decade ago had been learned.