Train ride to Mombasa that shaped my destiny

Dr Peter Kimani teaches journalism at the Aga Khan University’s Graduate School of Media and Communications in Nairobi and is Visiting Writer-designate, Amherst College, in the US. His critically acclaimed historical novel, Dance of the Jakaranda (2017), a New York Times Editors’ Choice, re-imagines the complex race relations in colonial Kenya and soon after independence, revolving around the railway. PHOTO| YUSUF WACHIRA

What you need to know:

- The return trip to Nairobi was no less dramatic. A lad we nicknamed Benja – light, tall, thin; and whose voice had already broken – threatened in his booming voice to jump out of the moving train to retrieve a knapsack he had forgotten at the train’s departure lounge.

- Our class teacher, Mr Kibe, calmed him down. “You will be arrested if you jump out,” he cautioned, before offering helpfully: “This is Mombasa. Nobody will touch your bag. They will think it’s a djinni disguised as a bag…”

- Nonetheless, Mr Kibe had the station master radioed and Benja’s bag was retrieved and forwarded to the next station on a cargo train. I recall Benja’s long face melting in delight at being reunited with his green bag.

I can still visualise the radiant smiles from hordes of boys and girls in checked blue-white uniforms, as the horn sounded to announce the train’s departure that breezy August evening in 1985.

I was 14, wing-eared and wide-eyed, somewhat bewildered by the bedlam around Nairobi’s Railway Station. We were on a school tour – I and about 50 other youngsters from St Paul’s Primary School, off Jogoo Road in Nairobi. This was the treat of our lifetime, the first long trip for a majority of us, so we giggled endlessly at the rocking movements of the train.

We hardly slept, even though all we could glimpse outside were the trees and shrubs that hurtled past – transmogrified into grotesque creatures at every turn – or a faint light winking in the distance. Alternately, we wandered into the next coach, where we saw men sleeping in luggage racks.

Showers of rain greeted us when we arrived in Mombasa, but that only appeared to buoy, not dampen, our spirits. This was a strange place, some mumbled. The rain had failed to shake off the heat.

That vista of a hot, drenched Mombasa has stayed with me, as has my first sighting of the Indian Ocean. There it stood in its full, blue majesty, zooming way beyond the eye’s gaze. The biggest water mass that I had seen in Thiririka — the small stream in Gatundu where I learnt to play — shrunk embarrassingly in my mind.

But this was no time for reflection. We plunged in and played in the ocean. Mburi – so nicknamed because he acted like a goat most of the time – pulled down the pants of a girl named Mary as she swam. In the evening, Mburi pulled yet another stunt: he placed a coconut shell on the face of Owaka as he slept. Owaka had squint eyes, so when he turned in his sleep and the shell rolled and scratched his face, he woke with a start and squinted even harder to examine his strange find.

When fingers were pointed in Mburi’s direction, he denied, in that slow speech of his, allowing only, falsely, that he had seen Owaka eating coconut as he slept, and so may have accidentally eaten his way to the shell in his sleep.

On the second day, somebody pulled a quick one on me. My pocket money, a cool Sh30, was stolen from the jacket that I had left in the bunker. I cried my heart out; thinking about all the coconuts I had planned to buy folks at home.

Teachers instantly mobilised the pupils and an impromptu fundraiser was organised, realising some Sh25 — almost restoring me to my original status. I don’t know if the thief had the conscience to give back some of the loot, but the donated cash did not feel right. Some classmates grumbled that they hadn’t received even half that amount from their parents, implying I should have received less help.

I reprimanded myself for not having been vigilant enough, but I never visualised any of my classmates as thieves. From that experience, I developed a healthy scepticism. I could probably smell crooks from a kilometre. That was the last time I had money pinched from my pocket.

NO LESS DRAMATIC

The return trip to Nairobi was no less dramatic. A lad we nicknamed Benja – light, tall, thin; and whose voice had already broken – threatened in his booming voice to jump out of the moving train to retrieve a knapsack he had forgotten at the train’s departure lounge.

Our class teacher, Mr Kibe, calmed him down. “You will be arrested if you jump out,” he cautioned, before offering helpfully: “This is Mombasa. Nobody will touch your bag. They will think it’s a djinni disguised as a bag…”

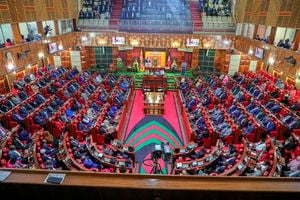

An old Kenya Railway train. PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

Nonetheless, Mr Kibe had the station master radioed and Benja’s bag was retrieved and forwarded to the next station on a cargo train. I recall Benja’s long face melting in delight at being reunited with his green bag.

We returned to Nairobi without any further incident, but the rail continued to intersect with my life more regularly the following year, in 1986, when I joined a public high school on the other side of town, in Nairobi’s South B. I noticed, without it making immediate sense, the economic disparities that define Kenya. Many students were dropped by their parents by car; others took the bus, many others took “Route One One” (also known as Route 11), which was euphemism for walking – putting one foot in front of the other.

There was a large gang that walked to the estates in Eastlands. In a few minutes, we would leave the well-paved, gated boulevards of South B, to the dust tracks that cut through the Mukuru slums, then a tapestry of iron and paper shacks that seemed held together by some mysterious force, other than carpentry.

The highlight of the walk was the small, murky stream that carried industrial effluent, human waste, or both. Crossing it was a delicate balancing act: if one missed a step, the hop-step-and-jump would end in a dive into the brown waters.

It got worse when it rained as the rocks would be submerged. A brave soul would lead the way, remove his shoes and roll up his pants. One shaky leg would waver at the push of the currents, and some of us would shake our heads and turn away — opting to take the longer route that passed outside the Mater Hospital, before navigating back to the industrial district.

We called the stream River Jordan, inspired by the reggae singer, Burning Spear (Winston Rodney), a literal and metaphoric obstacle that stood in our pathway to education, but also the link to our homes.

I liked it when it rained because that was the only time I would receive bus fare from my mother, and she would chuckle as she unzipped her purse: “Even the slightest of drizzle floods the rivers in your way!”

Most of the fare, naturally, would be saved to buy a blank tape for recording the next Bob Marley album; another portion would end up at the school canteen for a combo of chapati and sausage.

After crossing the Jordan, or navigating around it, we trekked joyfully through the industrial district in pairs, or in threes or fours. Some strode briskly or strolled leisurely, sharing stories that staved off the pangs of hunger and energised our tired limbs.

COVERED 10 KILOMETRES

I estimate we covered about 10 kilometres both ways, though some walked a little further, a portion of which featured walking by the railroad, a knapsack lapping on the back, patting us on.

At times, we would happen upon the passenger train and watch a tourist stare out the window in a preoccupied manner. Or the goods train would honk its horn to urge everyone out of its way.

And the gang of Eastlands would disperse towards their estates, the Kaloleni folks the first to arrive, followed by the Makongeni lads. We would reach our hood, Gava, abbreviation for Government Quarters, and say goodbye to folks headed further down to Jericho, Maringo and Makadara.

Considering the physical barriers we encountered along the way, from crossing swollen streams to crossing railroads, not to mention the great sacrifice made by our parents, there was the expectation that we’d take education seriously. I’m not sure I did, perhaps a little distracted by reggae and the dream of growing dreadlocks.

But one of the walking boys of Eastlands would emerge tops in our class. He nearly suffered a mental breakdown in the last week to our final-year exams, fearful that he’d tumble after years of success.

The rail also harboured happy memories for others in my life: my son’s Cucu, who commuted by train from Mombasa to the highlands of Eldoret to go to school, thought the train symbolised the nation’s epoch, when it felt safe to venture in any corner of this great land and proclaim your Kenyanness.

“The systems worked,” she often says wistfully. “The buses ran on time, the trains were scheduled, garbage was collected, the streets were lit…”

So, when or where did we lose the plot? It seems fitting that the Nairobi Railway Station, the site of our eventful dispersion that eventful August night in 1985, is the answer to that question.

The train station was the genesis of Nairobi, about 120 years ago, and it wasn’t supposed to serve anything beyond a supply station for railway workers. But then, to use that clichéd expression, life happened, and Nairobi was born – without any discernible plan.

And so did the townships that sprouted along the railway line, weaving together communities that became connected through commerce. And a nation was born.

That, too, was accidental. The British settler economy was built around the idea of tilling the land – by coercing locals or enticement – and shipping away the produce to Britain. The rail cut through areas that the British considered productive for exploitation.

And the areas that had nothing remained off the radar. When I toured North Eastern Province a decade ago, a Mandera resident sneered: “When you get to Kenya, please give my greetings to the people of Kenya…”

The train delivered more than just townships; it offered a solid template of how racial segregation could be enforced by offering first, second and third class compartments assigned according to racial hierarchy. This was replicated in the city settlements that were set aside for Whites, Indians, Arabs and Africans.

Some things never change. The land question continues to fester, as it did when our forebears protested the annexation of local lands to pave way for the rail.

And if the old rail was the most expensive investment that the British made in Kenya, they recouped, and continue to recoup their investment by shipping out what the land could produce.

Similarly, the new rail is the most expensive infrastructural investment in our history, underwritten by the Chinese. I have no idea what they hope to ship away, but our children and their children will repay that debt.

Talking about children, I met my childhood chum, Mburi, about 10 years after leaving St Paul’s. He was then a moustachioed youth in a big Afro. “I-am-a-preacher,” he announced in his slow speech.

DARKENED REGGAE NIGHTSPOT

It was around that time that I also met Benja in a darkened reggae nightspot, where he was swinging with a young, white woman. His face lit up delightfully, as it did at the sight of his lost, green knapsack, long time ago.

“Benja operates between Mombasa and Nairobi,” another former classmate confided afterwards. “He goes fishing for white women in the beaches of Mombasa…”

The bright boy from my class became a top technocrat, his claim to fame being his implication in the theft of Sh5bn from a government ministry.

I have no idea if Mburi and Benja’s life choices were in any way influenced by their memorable trip to the coast, or if the bright-boy-turned-big-thief was tempted into larceny by the blistering walks by the railway.

But I have no doubt that the train ride to Mombasa was a defining moment. I became a storyteller, first retelling tales about reggae that were first shared in those walks by the railway, for readers in this newspaper. And 30 years later, I would return to the story of the rail, drawing from the 1985 trip as foundational memory — the first and last time I took the rail from Nairobi to Mombasa.

The ocean remains a powerful symbol of the endless possibilities that the world can offer, and I am glad that the train delivered there, some 30 years ago.