What can’t politicians do in the name of the people?

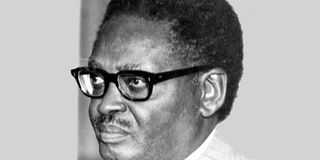

Former Angolan president Agostinho Neto. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- There is a clarity of imagery and a cry on behalf of the long-suffering Angolans that mock the history of Neto’s rule in Angola and what the country is today.

- The poem, although giving the illusion of stanza breaks, is really one long statement; a statement of hopeless life under white rule.

- The hope of “life recovered” that Neto speaks of in the poem may be only a hope of those who rule in the name of many in Angola. For Angola is today described as one of the leading African economic miracles.

Many pan-Africanists will swear that Agostinho Neto is among the truest of African intellectuals.

There aren’t many of his type, not in the myth of Africa’s anti-colonial struggles.

Or should we say there haven’t been many African heads of state that can be described as thinkers and people’s presidents.

Neto is known not just for having led Angola to independence from the Portuguese in 1975. He wrote memorable poetry.

There is an anthology of poetry that has been used in many English speaking African schools: the Penguin Book of Modern African Poetry. In it, you will meet Neto celebrating Africa and Angola.

But Neto the poet was a different person from Neto the politician. And so it came as a shock to read about Neto being implicated in the murder of his countrymen, in a recently published book, In the Name of the People by Lara Pawson.

When you read Neto’s poem, Farewell at the Moment of Parting, you will be struck by its urgency and prophetic vision.

There is a clarity of imagery and a cry on behalf of the long-suffering Angolans that mock the history of Neto’s rule in Angola and what the country is today.

MONSTER OR SAINT

Neto writes, “My mother/(oh black mothers whose children have departed)/you taught me to wait and to hope/as you have done through the disastrous hours But in me/life has killed that mysterious hope. I wait no more/it is I who am waited. Hope is ourselves/your children/traveling towards a faith that feeds life.

We the naked children of the bush sanzalas/unschooled urchins who play with balls of rags/on the noonday plains/ourselves/hired to burn out our lives in coffee fields/ignorant black men/who must respect the whites/and fear the rich/we are your children of the native quarters/which the electricity never reaches/men dying drunk/abandoned to the rhythm of death’s tom-toms/your children/who hunger/who thirst/who are ashamed to call you mother/who are afraid to cross the streets/who are afraid of men. It is ourselves/the hope of life recovered.

The poem, although giving the illusion of stanza breaks, is really one long statement; a statement of hopeless life under white rule.

The poem powerfully evokes the tragedy of black Angolans, cursed to work for the benefit of their white rulers, with violence and death hovering over them. So then, how did it happen that such a visionary man like Neto and his co-rulers didn’t shy from using violence to silence dissenting fellow Africans after independence?

This is a question that will haunt the reader from the beginning to the end of In the Name of the People.

The monstrosity of the violence in May 1977, an event that is little known to the rest of Africa, when the government violently suppressed a protest against the failures of the regime, still defines life in Angola today, says Pawson.

According to her, the event is described as a protest, an uprising or a coup depending on whom you speak to in and out of Angola, or on the source you read.

But, essentially, what happened is that some members of the MPLA — Angola’s independence and still ruling party — chose to protest publicly against the party in the streets of Luanda on 27 May 1977.

They were joined by a few members of the armed forces. Thousands of the protesters, described by Neto’s side as “factionalists,” were beaten up, jailed or simply killed by the police and the army with the support of Cuban forces who were then in Angola.

Like it happens in such situations, some of the dead were buried in mass graves while those that survived either went into exile or disappeared from public life.

REMAIN BURIED

The hope of “life recovered” that Neto speaks of in the poem may be only a hope of those who rule in the name of many in Angola. For Angola is today described as one of the leading African economic miracles; it is at the front of the latest illusive mantra to be found in the financial pages of international media on “Africa rising.”

For Africa is surely rising. But evidence suggests that the continent is still just a major exporter of raw materials — Angola being one of the big exporters of oil — and a net importer of expensive goods from America, Europe and China.

Pawson travels from London, through Lisbon to Luanda, looking for stories about the May 1977 rebellion, known in Angola as vinte e sete.

Very few, like Maria Reis in Lisbon who lost her husband, are willing to speak about the horrible event whose consequences are yet to be properly calculated or known. The tragedy may be four decades old but the memories haunt the victims and their relatives.

Those who were on the ruling side would prefer the bones of the victims to remain buried. Some of the victims and their relatives, too, would rather the past remains in the past.

But others like Joao Vieira Dias Van Dunem, whose brother was executed for involvement in the uprising, and who thinks Neto is squarely to blame for Angola’s misfortunes — say it is the silence that enveloped Angola in the aftermath of the killings that emboldened and continues to embolden the ruling class to ignore the racism and poverty that afflict Angola today.

In the Name of the People leaves you in no doubt that rulers can commit unimaginable crimes in the “name of the people”.

It is on record that Neto said the rebellion would be crushed “in the name of the people.” For although the protest was a case of intra-party differences between the netista — those supporting Neto — and the nitista (those supporting Nito Alves, who had been a member of MPLA and Minister of the Interior until October 1976 when he was expelled from the party), the winning side didn’t stop to consider the grievances. They simply tightened their grip on power and used the DISA — Angolan Directorate for Information and Security — to eliminate the “factionalists” and impose a regime of silence among the populace.

Consequently, a country that had fought for independence on socialist ideology degenerated into an unequal society where blacks were alienated from the mainstream economy and politics.

Inequality, racism, lip-service to socialism, dalliance with Marxism and Communism from the USSR and China, among other omissions, led to the wasted years of the civil war between MPLA and UNITA.

But after Jonas Savimbi’s death, the rulers in Luanda simply became too comfortable as globalisation and neo-liberal economic policies celebrated the “market” as the only tool for progress. However, Angola won’t pull of a miracle that even the poster boy of market neo-liberalism in Africa in the recent past, Ghana, hasn’t managed to.

STATE-CENTRIC HISTORIES

The idea that the one-day rebellion in the MPLA in May 1977, an uprising that reflected not just fissures in MPLA but significant government failures, can be forgotten and that Angola will move on is a bad one.

Pawson painstakingly shows, through interviews with victims or Angolans whose relatives were victims of the killings, and those who were in government, through personal reflections from the time she spent in Luanda as a journalist, and through a thorough critique of the literature on Angola, that possibly the worst curses of postcolonial African states include the “killing” of internal party differences, cover ups of political murders and production of state-centric histories by both local and foreign supporters of the regimes.

In this case, many British “Africanists” and even journalists simply gloss over the horror of May 1977.

Angola today, just like ZANU-PF in Zimbabwe, is still ruled by the independence party, but one which seemingly has a history of not brooking intra-party democracy.

Can such parties ever govern democratically, or in the name of the people. What hope do the Angolans that Neto recalls in his poem have?