Faithful house servant who has left a mark on families he has served

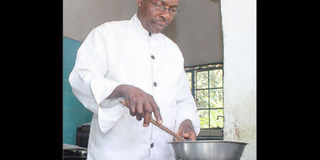

Veteran Chef Henry Mudembei when he spoke with Sunday Nation. PHOTO| ANTHONY OMUYA

What you need to know:

- Mr Mudembei could almost hear the money telling him to pick it and hide it. Surely, his boss couldn’t remember money lost months ago. But he decided otherwise.

- In the Desai House compound, there is a servant’s quarter that has been Mr Mudembei’s abode since he started working there in 2006. Mr Desai’s mother and father have died during his stay at the homestead .

- “I did not want to make this body of work about rich-versus-poor or white-versus-black,” Mr Bonn told Refinery29, an American website, in February 2016.

- So pleased was Ms Hasson of Mr Mudembei’s work ethic that about 25 years ago she bought him a three-acre piece of land in Kitale, Trans-Nzoia County — where his family homestead run by his wife Esnas Jahenda is located — kilometres away from his ancestral home in Sabatia, Vihiga County.

There are many Kenyans like Mr Mudembei working tirelessly in homesteads across the country, faithfully running affairs of their bosses behind the scenes

Henry Mudembei was cleaning his employer’s house when he found a wad of crisp notes amounting to Sh100,000 stashed between books.

It was about a year since his boss Sandeep Desai had reported losing the cash.

Mr Mudembei could almost hear the money telling him to pick it and hide it. Surely, his boss couldn’t remember money lost months ago. But he decided otherwise.

“Isn’t this the Sh100,000 you were talking about a year ago?” he remembers asking a speechless Mr Desai.

His boss had written off the amount on the week it got lost. It was part of a sum he had hidden in different places in the house.

“Ironically, it was just between some books which were being cleaned and it reappeared from nowhere,” says Mr Desai.

The scene played out about eight years ago and it cemented the place of Mr Mudembei in the Desai household. He is now in his 11th year as the only live-in worker at the home.

Mr Mudembei, 67, has spent the better part of the last 30 years living such a life.

“Cook”, “house manager”, “house servant”, “house-help” and “cooking assistant” are some of the terms his past employers have used to describe him in various written recommendations he has.

Born in Vihiga County in 1950, Mr Mudembei has been an occupant of servant quarters in households of various people living and working in Nairobi.

One of them is Dieter Hollig of Nova Chemicals, whom Mr Mudembei worked for between 1987 and 1988. There is also Ricca Hasson, a consular attaché for the Italian embassy, who employed Mr Mudembei from 1989 to 1994. His other boss was Mr Nicholas Kotch, then the East Africa bureau chief of Reuters, who employed him between 1995 and 1998.

Another one is Ms Catherine Spring of Unicef who employed him between 1998 and 2001. The list of his former employers includes Mr George Muchai, a trade unionist who was shot dead in Nairobi in February 2015, two years after being elected as the Kabete MP.

Lifestyle met Mr Mudembei for a chat at Mr Desai’s home, which is the famous Desai House in Parklands that could soon be gazetted as a national monument if a process started in October 2016 by the National Museums of Kenya bears fruit.

The house was used by the current 49-year-old occupant’s grandfather Jashbhai Motibhai Desai to host meetings by individuals involved in the push for independence in Kenya.

In the Desai House compound, there is a servant’s quarter that has been Mr Mudembei’s abode since he started working there in 2006. Mr Desai’s father died during his stay at the homestead.

A casual chat with Mr Mudembei on his experiences brings up interesting points about living with one’s employers.

In terms of coming into contact with cash like he did with the Sh100,000 at the Desai household, he confesses that if he had been giving in to temptations, he would have stolen lots of money.

“I could be owning a matatu by now. But it’s better to go slow so you can get yours tomorrow; not to steal,” he told Lifestyle.

And he thinks he has proof of the consequences of having sticky fingers: “All the men with whom I started working with in Nairobi are now back in the village without much.”

There have been times, he says, when he has had to guard “sacks full” of money, as much as Sh5 million in cash.

There were also moments, way back in 1989, when he says he was being given hard cash every month to take to his employer’s landlord as his employer left for work.

The rent used to be Sh65,000 per month then. That was enough to buy a piece of land; but he never once thought of being clever with it.

"When you see some property, know that it belongs to your boss; it’s not yours. Because he has employed you as staff, you just leave it the way it is,” says Mr Mudembei.

Taking care of cash and possessions is not what he is employed for. His main job is to prepare meals for his employers and if the reviews his former bosses have been writing are anything to go by, then Mr Mudembei, who did not go past primary school in his education, seems to have made a successful career in a line of duty not considered the most glamorous but which many people in urban areas cannot do without.

In his recommendation letter of December 30, 1988, Dieter Hollig wrote: “Henry has been our employee from October 1, 1987 until now, the end of December 1988. Henry is a very pleasant and extremely honest man, ever so helpful and with a little guidance, also a good cook.”

Ricca Hasson, in her August 8, 1994 recommendation letter, was also full of praise. She started by saying that Mr Mudembei had been “under my personal employment since I arrived in Nairobi on March 1, 1989.”

“He has been working alone and taking care of the whole house and myself to my full satisfaction. He has proved very honest, above all other qualities concerning him: loyal, discreet and a very hard and good worker. He has learnt from me to be a good cooking assistant and is presently a good cook,” noted Ms Hasson then of the Italian embassy.

So pleased was Ms Hasson of Mr Mudembei’s work ethic that about 25 years ago she bought him a three-acre piece of land in Kitale, Trans-Nzoia County — where his family homestead run by his wife Esnas Jahenda is located — kilometres away from his ancestral home in Sabatia, Vihiga County.

“That was out of luck, following how I had worked diligently,” he recalls, noting that an acre was selling at Sh35,000 then.

Mr Nicholas Kotch, while departing from Kenya, wrote a letter to Mr Mudembei on July 9, 1998.

“You have been working hard for the three years we spent together and we have appreciated the fact that you ran the house to our satisfaction,” stated the then Reuters journalist.

Ms Catherine Spring, then leaving Kenya while working with Unicef, also penned a letter appreciating Mr Mudembei for running domestic duties between August 1998 and July 2001.

“Henry worked for me as a full cook and househelp. His main responsibilities included preparing all meals for the family, keeping part of the house (living room, kitchen and master bedroom) clean, making shopping lists each week and doing the laundry for my husband and myself.

In addition, he has assisted in the organisation of parties for many guests. He performed his duties satisfactorily.”

His current boss, Mr Desai, is also full of praise for him.

Veteran Chef Henry Mudembei with employer Sandeep Desai. PHOTO| ANTHONY OMUYA

“After all these years, he has maturity and a deep understanding of life in Kenya. He has great knowledge which he shares and imparts always at the right time; the sort of knowledge you rely on from a father figure and a good friend,” says Mr Desai, an entrepreneur-cum-art collector.

Mr Desai, just like Ms Hasson, also plans to buy Mr Mudembei a piece of land as a retirement gift for having served his family diligently.

“We have already located the land we want to buy and we’re working on it. It’s within a prime area in Kitale and we’re in negotiations,” said Mr Desai. “It will be a total pension with no limitations. Whatever Henry wishes, I’m behind him to support it fully.”

As his boss heaps praise on him and laid out the plans, Mr Mudembei just sat calmly on his chair, and one would immediately discern that he has mastered the art of keeping quiet when his boss is talking.

Only when Mr Desai is done that Mr Mudembei opens up. We ask him the secrets to survival in his line of work. One of them, he says, is patience. Of all the people he has worked with, Germans are the most demanding. “They want you to be very understanding. And they don’t want you to lie to them,” he says.

Additionally, someone in a career like his should not be into drugs or alcohol because they will easily mess things up.

Another secret, he says, is that one should always eschew the regular excuses to take time of work.

A father of seven, Mr Mudembei takes a one-month leave per year and rarely goes out of his workplace except when there is a funeral or some other pressing demand.

“If he has to go, he will return to duty before you even need him to be here,” says Mr Desai.

It also is common knowledge that every family has skeletons in the closet and a house help will inevitably encounter such in their line of duty.

In one instance, Mr Mudembei’s boss used to be violent towards his wife whenever he was drunk.

“When he was very drunk, he didn’t want to see his wife but he could tolerate me. The wife could often say, ‘I don’t know what you do to my husband so that he can like you when drunk and hate me,’” recalls Mr Mudembei.

But despite the drama he has been witnessing, his philosophy has been to keep a safe distance. If need be, he sometimes acts as an arbiter.

“If you start involving yourself in other people’s affairs — when they are fighting, for example — and you try to take sides, it makes a bad situation worse. You are supposed to provide a solution,” he says.

There are many Kenyans like Mr Mudembei working tirelessly in homesteads and households across the country and running affairs of their bosses behind the scenes.

A Madagascar-born photographer in 2016 published photos of 18 house servants in Nairobi, Naivasha, Nakuru, Lamu, and Malindi which he had taken during his stay in Kenya, with the aim of exposing the reality of the workers’ lives.

“I did not want to make this body of work about rich-versus-poor or white-versus-black,” Mr Bonn told Refinery29, an American website, in February 2016.

“The initial drive behind this was to bring in the foreground people who spend their entire lives in the background managing other people’s lives — and in the process, find out about their lives, dreams, and hopes,” he added.

Mr Bonn’s lenses captured people like 50-year-old Margaret from Bondo, Siaya County, who had been a housemaid for one household for over two decades. He also captured 42-year-old Salim who is a cook and housekeeper for a family home in Lamu. He equally photographed 32-year-old Evelyn who had been a nanny at a family for more than a decade.

Mr Bonn called the series of photos “Silent Lives” and he had an interesting observation about the people he captured.

“The men and women I photographed for ‘Silent Lives’ are often happier than the people who employ them who have far more. So what does that say about the [consumerist] society we have built for ourselves? We always need more, thinking that it will make us happier. But it does the opposite,” he told Refinery29.

Is Mr Mudembei among the happy lot? Apparently, yes. Asked if he could have lived his life differently if he were to start all over again, he says he is happy with what he has achieved.

“You should bank on things that can be seen. That’s why you see some people suffering from stress and other diseases like ulcer, because they keep thinking of things they could have done,” he says.

Mr Mudembei was born in Sabatia, Vihiga County, to a father who worked as a white man’s gardener in Turi, Nakuru County and a peasant mother. He was a fourth born of 10 children.

After completing his primary school studies at Rusingiri Primary School, he went to Turi to live with a relative, and afterwards he took various jobs at factories in Nakuru and later in Webuye.

He moved to Nairobi in the late 1980s in the hope of a better life. As fate would have it, he became a domestic cook and though he started off without training, some of his employers facilitated his learning.

While working with Dieter Hollig, he was sponsored by his boss to Utalii College in 1987 where he took a short course on salad dressing among other topics.

Ricca Hasson also took him to an Italian restaurant in Muthaiga where he learnt making pastries. Another employer took him to the Belgian restaurant to learn how to cook.

Now, Mr Mudembei believes he can prepare cuisines for different groups of people and cultures — from pasta to pizza.

“For the last three weeks, I have been taking a picture of my food before I eat it. I have not been served one meal from Henry which I am not happy with,” says Mr Desai.

“I don’t ask him to prepare a certain dish. I just sit and wait and it will always be perfect,” he adds.

Mr Mudembei’s current responsibilities include shopping for food and household items and preparing diet plans. He is also always involved in welcoming the many guests that visit the Desai household.

“All my friends who visit, my artist friends, the business community, my personal friends — I sometimes get the impression they prefer Henry to me. They come sometimes to see Henry. They ask about Henry first and I second,” Mr Desai says, laughing.

Some of the artists friends of Mr Desai have been inspired by Mr Mudembei’s service that they drew portraits of him. One portrait was done by Dale Webster, a former arts lecturer in the United Kingdom in 2012.

After the long service in homesteads spanning over three decades, Mr Mudembei wants to call it a day.

“I see that my strength has reached a level where I shouldn’t push much. I should leave with some strength to enable me take care of goats and sheep,” he says.

If not for a land dispute that saw bulldozers descend on the Desai compound early last year, Mr Mudembei could have retired in 2016. But now he will have to serve the Desai homestead till at least February 2018.

“We would like the retirement to happen at a good point when everyone is happy,” said Mr Desai.