When it comes to religion, we must accept that most of us are lost

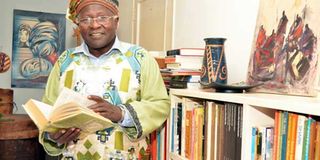

David maillu is a highly acclaimed veteran writer, African thinker and philosopher. PHOTO | FRANCIS NDERITU

What you need to know:

- Most religious teachings are tied to our cultural teachings, so in a way, what I call the African religion is also very influenced by culture, and I believe that any good religion should feed off culture and any good culture should feed off religion.

- Life is very naked and there is nothing that is a lie in these stories. In Kenya, touching the subject of sex is like touching a raw nerve, but the fact that Kenyans read the stories should tell you that the stories resonate with them.

- The systems in our country have not been good at promoting our cultural values, so I think that it is not as if the young people cannot learn. They just need a place to go and learn. We need to begin from a point of curriculum inclusion in the education system and extend this to our homes.

A lot of your writing is clearly pointed towards the preservation and the upholding of African cultures. Why should the young person today hold on to any particular culture at a time when they are bombarded with globalisation?

At the outset, I would like to say that young people need to grow up with the acknowledgement that their cultures are very central in their lives. Even the most advanced civilisations in the world are based on people’s cultures.

Our cultures mould us and we quickly begin to realise that it is difficult to operate outside a cultural root.

So to answer your question, if you acknowledge that you have an African base, you can survive any oscillations occasioned by contact with other cultures and learn to only pick the practices that suit what you want to be in the long run.

What do you think is the importance of any form of religion to today’s youngster? Is it possible to reclaim the true essence of the ‘African religion’ as you put in The Sacred Book of KA?

When it comes to religion, we must begin by accepting that most of us are lost. And this applies to all religions, not just Christianity. Religion is a very powerful tool and it is very dangerous to overlook it. Religion (well learned and understood) for the young person today can seep through all aspects of their lives and affect everything that they do for the better, including how they approach challenges in life and how they interact with friends and colleagues.

Most religious teachings are tied to our cultural teachings, so in a way, what I call the African religion is also very influenced by culture, and I believe that any good religion should feed off culture and any good culture should feed off religion.

In your books, especially in the most recent ones, your protagonists are near perfect young people. Mwanzo in Mwanzo the Nairobian and Kivindyo in Man from Machakos easily come to mind. Do you think the youth today can attain that level of ‘clean’? What is your vision for such characters?

Yes, I think they can achieve this high level of morality. As for the vision, I created these characters to try and technically solve the problem of moral decay through the provision of models. As a writer, I also find that it is very difficult to not take sides, and this comes up because I model some of these characters on myself; I value discipline and I have always been interested in truths, so in a way, writing carries a big part of a writer’s psychology as they reflect themselves in their writing.

Some of your books, such as After 4.30 and My Dear Bottle are considered controversial because of the explicit way in which you write about the subject of sex. Many who have read these two books claimed to have been scandalised – were they being pretentious?

I read a lot of pretence in this kind of reaction. Life is very naked and there is nothing that is a lie in these stories. In Kenya, touching the subject of sex is like touching a raw nerve, but the fact that Kenyans read the stories should tell you that the stories resonate with them. But I did not at all anticipate that kind of reaction from the audience; I only wrote the books to interpret the complexities in these relationships, not to provoke.

What, in your opinion, is the best way to bring the Kenyan youth, especially those born and raised in urban centres close to their aesthetics as Africans?

The problem is with the older generation because for a majority of them, there has been no deliberate process to inculcate these values into the younger generation. Also, the systems in our country have not been good at promoting our cultural values, so I think that it is not as if the young people cannot learn. They just need a place to go and learn. We need to begin from a point of curriculum inclusion in the education system and extend this to our homes.

Do you think, in your heart of hearts, that Kenya will become better if we change the system of learning?

It all depends on what we are changing it to because change in itself does not have any guarantees. The change has to be linked to ourselves and address our socio-cultural problems, otherwise we should not bother because it will be like the act of changing wine from one glass to another. The wine does not change, the containers do.

Are there authors that you admire?

Leo Tolstoy for his intense understanding of human behaviour and Chinua Achebe for a lot of his earlier works.

For some people, books are just stories and so they do not have time to waste. What is your advice to such a person?

Contrary to what they believe, books have a lot to do with them, but this problem goes far back to not developing a reading culture in this country and people reading only to pass exams; a wrong focus.

What advice can you give to a young person who is just starting out on the writing journey?

Do not begin to write with the aim of earning money from it. Just follow your urge to write and see what happens.

What is your latest title?

A friend in Need.

What is your philosophy of life?

Live life very honestly.