Why Ole Kulet, a winner yet again, deserves more respect from critics

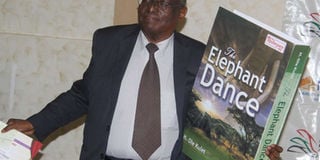

Award-winning author Henry ole Kulet after being named the winner of the 2017 Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature in Nairobi last weekend. JOSEPH NGUNJIRI | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Another key concern one may deduce from reading Kulet’s novels has to do with the persistence of a certain image of the Maasai people, especially in the Western reading public. One of the world’s indigenous peoples, the Maasai image in the Western consciousness is that of a kind of a “noble savage”.

- Popularised by settler writings and by such canonised Western writers like Ernest Hemmingway in Green Hills of Africa (1935), this was an image that Kulet sought to debunk through his realistic portrayals of the Maasai culture and way of life.

The year 1971 marked a significant shift in the development of Kenyan literature. That was the year Charles Mangua published Son of Woman, his sassy thriller of urban life.

Irreverent and light-hearted, the novel focuses on the escapades of one Don Kiunyu: “I was conceived on a quid and mother drunk it…” Kiunyu tells us in the opening line.

Raised by his prostitute mother and then by her prostitute friend after his mother passes on, Kiunyu ultimately graduates from college and gets a civil service job.

He then begins his life on the fast lane of bar hopping, illicit dealings and crime that climaxes in a robbery that sees him imprisoned.

Son of Woman marked the birth of the Kenyan popular novel and was eagerly embraced by a reading public that up to now had very little to go by outside the “high serious” novels of Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

It firmly establishing its author as the principal and founding interlocutor of what Roger Kutz styles as “urban fears / urban obsessions” in East African literature.

The novel had a profound influence on other East African writers including Ngugi who, in a wink of recognition of the unfolding trends, prominently infused popular elements and themes in his novel of the 1970s Petals of Blood (1977).

Mangua made an enduring contribution to the development of East African literature and was awarded the Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature for his second novel, A Tail in the Mouth (1972).

The same year Mangua’s trail-blazing novel came out; another new writer by the name Henry Ole Kulet was staking his claim to the literary space.

His first novel, Is it Possible? (1972) went against the strain of both the politically committed fiction that had been characteristic of the East African novel and the emerging trend towards popular, urban-based fiction.

Kulet’s novel hearkened back to the cultural narratives of nationalist imagination of the 1960s — works like Ngugi’s The River Between — which had their exemplar model in Chinua Achebe’s classic novel Things Fall Apart.

In a very real sense, Kulet’s novels – Is it Possible?, To Become a Man (1972), The Hunter (1985), Moran No More (1990) and Daughter of Maa (1990) were narratives of the falling apart of the Maasai culture figured against the unrelenting thrust of modernity in post-colonial Kenya, a development that engendered uncertainties relating to individual and communal identity among the Maasai.

Kulet’s preoccupation with the Maasai culture and identity has seen some critics tag him as a Maasai writer. In answer to what he thought about such a characterisation, Kulet said that as a young writer, he was gravely concerned about the fast disappearing culture. But he is also aware of how such a tag diminishes him as a writer.

ANOTHER KEY CONCERN

Another key concern one may deduce from reading Kulet’s novels has to do with the persistence of a certain image of the Maasai people, especially in the Western reading public. One of the world’s indigenous peoples, the Maasai image in the Western consciousness is that of a kind of a “noble savage”.

Popularised by settler writings and by such canonised Western writers like Ernest Hemmingway in Green Hills of Africa (1935), this was an image that Kulet sought to debunk through his realistic portrayals of the Maasai culture and way of life.

In novel after novel, the apparent nobility of Maasai culture is shown to be founded on a deeply entrenched patriarchal infrastructure that victimises girls and women by exposing them to harmful cultural practices such as genital mutilation and gender-based violence.

Perhaps because of the Western fascination with the Maasai, Kulet’s books have reaped a bountiful divided in the West with his books being translated into several European languages including French, German and Swedish.

It is his Western readers who have been responsible for tagging Kulet as a Maasai writer, a tag that has sometimes been uncritically adopted by some Kenyan critics.

Although he is not unduly concerned about this tagging, Kulet underscores his dual identity both as a Maasai — and a Kenyan writer.

Indeed in a career spanning close to five decades, Kulet has succeeded in forging the Maasai story into the framing narrative of his engagement with issues of concern in the broader Kenyan story.

In Bandits of Kibi (1999), the Nakuru-based author draws on his experience of the so-called ethnic clashes that rocked parts of the then Rift Valley Province in the early 1990s to affirm Kenya’s national identity against political entrepreneurs who would stop at nothing in their reckless pursuit of power based on ethnic mobilisation.

A sombre reflection on the “pitfalls of national consciousness”, the novel prophetically foreshadows the near-disintegration of the Kenyan nation following the 2007-2008 post-election violence.

In Blossoms of the Savannah (2008), the author tackles the tricky problem of female genital mutilation in a direct and culturally sensitive way.

Simultaneously a love story and also a story of a woman’s emancipation, Vanishing Herds (2011), depict the transformation of Norpisia from a shy, traditional girl, into a champion of environmental conservation.

But even as he critiques the worst of the Maasai culture, Kulet is cognisant of the fact that the culture has much that could be useful.

In a situation where a transcendent modernity threatens to erode all local knowledge, Kulet’s novels are a rich repertoire of indigenous epistemologies that might yet offer important lessons in conservation.

An abiding concern throughout his novels is the examination of the nexus between human culture and nature; the ecological ramifications of post-colonial modernity on his characters’ consciousness.

This is the thrust of Kulet’s most recent novel The Elephant Dance (2016), a searing critique of corruption and how the powerful dispossess the indigenous people of Konini Forest under the guise of development.

The novel, which is in the shortlist of this year’s Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature, cements Kulet’s credentials as the foremost voice of environmental conservation in East African literature.

The most decorated writer aside from Ngugi, Kulet deserves a lot more critical attention from the academy than he has received.

Goro Kamau is a senior lecturer in Literature and Director of Research, Extension and Consultancy at Laikipia University.