A walk through the mind of a cancer sufferer and her caregiver

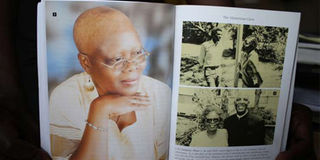

Prof Emmy Mwenesi Gichinga died on January 28, 2010, and it took some 18 months for he husband to peruse the diary without which the book sub-titled: “Emmy Gichinga’s battle with Cancer” would not have been what it is. PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Emmy and her husband had agreed never to read each other’s text messages because, as pastor and counselling psychologist, they knew about many marriages that had broken because of that.

- On Friday, I asked the author at which point he had read the diary, given cellphone contents can be very similar to diary entries. That is when he revealed how long it had taken him to read his wife’s diary.

There are books you read and instantly wish to share with others; not even as a book review, for which this writer has considerable passion, as a literature student, but for the poignancy of its message.

Such is the case with Pastor John Gichinga’s Cry of the Heart, which is a veritable walk through “the valley of the shadow of death” — an apt refrain throughout the 155-page book that draws heavily from the diary of his dying wife of 32 years. Not surprisingly, Gichinga makes ‘In the Valley of the Shadow of Death’ one of the 11 chapters of the emotionally-charged book.

Prof Emmy Mwenesi Gichinga died on January 28, 2010, and it took some 18 months for he husband to peruse the diary without which the book sub-titled: “Emmy Gichinga’s battle with Cancer” would not have been what it is.

Emmy and her husband had agreed never to read each other’s text messages because, as pastor and counselling psychologist, they knew about many marriages that had broken because of that. On Friday, I asked the author at which point he had read the diary, given cellphone contents can be very similar to diary entries. That is when he revealed how long it had taken him to read his wife’s diary.

The 2014 Arba publication is one man’s walk with his terminally-ill wife — a grim reality amid increasing cases of cancer. It can be asserted that it is only by studying his wife’s mind months after she died that the pastor healed enough to even venture into a second marriage.

Terminal illness takes such a huge toll on the primary caregiver that few wish to discuss it once they have buried their loved one. Not only that, but grief, especially in the urban setting, where people tend to keep to themselves, is often seen as a private affair, best left to the bereaved to deal with.

Not so the retired Baptist church minister; in Cry of the Heart, Gichinga grapples with his wife’s cancer from the moment it is diagnosed in April 2009 to January 28, 2010, the day Emmy died.

Prof Gichinga, a lecturer at Tangaza University College, had less than 10 months to live after she was diagnosed with cancer. And yet, the valuable lessons shared by her husband over that period help one to appreciate the understatement of many an obituary’s cliché about “a long illness bravely born”. In reality, the phrase hides much more than those left behind would acknowledge.

Although most attention focuses on the terminally-ill, Gichinga brings out the rarely talked-about situation of the primary caregiver, the spouse in his case. Often, the caregiver needs just as much, if not more attention as the dying.

SYMBOL OF FEMININITY HIVED OFF

It is traumatic for the couple when that symbol of femininity is hived off. And then the chemotherapy, which results in hair loss; few men are prepared to confront that. The reality of a bald wife without the breast presents a challenge to the man, who is usually revolved at the sight.

A message to Gichinga from his sister-in-law, in which Emmy had complained about his reaction to her physical appearance, is an example. “I remember her narrating in pain how you reacted with shock when you saw her hair had fallen off; you told her to tie the head scarf. She said that when you saw her missing breast, it shocked you.”

If the pastor was not ready for the metamorphosis of his wife, it was equally true that he just did not know how to show affection to his wife by feeling her bald head or where her breast once was — a gesture she craved — without appearing “patronising or behaving in pity”. This “would have driven proudly independent Emmy, mad,” he writes. And yet, in “seeking to be safe, I presented myself as uncaring. We men need to learn this delicate balance.”

A major challenge caregivers face is patients’ mood swings between anger and self-pity. Emmy’s misinterpretation of her husband’s desire to restrain her from work is a typical case: “At times I feel like my husband makes some very unkind and insensitive remarks, e.g. ‘I have to use a stick to keep her down.’ Or ‘Who said you have to make food for us; we can eat bread.’”

An independent observer would read care in the husband’s remarks; and yet, they conveyed the opposite meaning to his wife.

Given the fair dose of such callous comments extracted from Emmy’s diary, it is amazing that the author surmounted them to make the book what it is: a walk through the mind of a cancer sufferer and the caregiver, both of whom needed support to stay the course. As Gichinga says, many spouses, mostly men, simply run away, abandoning their spouses to biological families.