As music plays: Was Beethoven a black man?

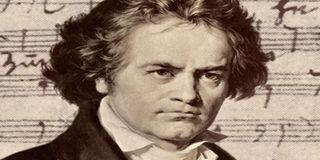

A quirky website claimed recently that the great composer, Ludwig van Beethoven, had African ancestry, and they had actually produced an analytical recording of his music to “prove” it. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- A quirky website claimed recently that the great composer, Ludwig van Beethoven, had African ancestry, and they had actually produced an analytical recording of his music to “prove” it.

- If you listen carefully to Beethoven’s music, with its “multiple rhythms”, the Black-Beethovenists claim, you will not fail to hear the “boomboom-doodleedum” of African drums behind it.

The English novelist E.M. Forster describes Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony as “the most sublime noise” ever to penetrate the human ear. This is in his novel Howard’s End, a London-set narrative that weaves a tender and intricate web of relationships around an old home in the early 20th century.

Forster uses “sublime noise”, which we in literary stylistics call an oxymoron, or rhetorical yoking of apparently contradictory terms, in the fifth chapter of the novel. I would recommend this entire chapter to anyone who has not savoured the beauty of English prose for some time as a truly good read. It may very well be one of the most sublime scribbles ever to leap to the human eye, and it is available online!

In Kenya, we know Forster best for his blistering anti-colonial novels, A Passage to India and Burmese Days. The latter, as you might remember, is the one I wrote study notes about, with my friend Richard Arden, and later made radio programmes at what was then called the Educational Media Services, with Margaret Ojuando and the honourable and illustrious Peter Anyang’ Nyong’o.

But it is Beethoven that brought Forster back to my mind, and it is a bizarre online claim and controversy that brought Beethoven to my mind. A quirky website claimed recently that the great composer, Ludwig van Beethoven, had African ancestry, and they had actually produced an analytical recording of his music to “prove” it.

ODE OF JOY

If you listen carefully to Beethoven’s music, with its “multiple rhythms”, the Black-Beethovenists claim, you will not fail to hear the “boomboom-doodleedum” of African drums behind it. Try it out the next time you listen to the “sublime noise”, or even to the Ode to Joy, the anthem of the European Union. I will certainly be straining to detect the isukuti, Kiganda bakisimba or bongo beats the next time I listen.

But it is not fair to confer our dear Africanness upon Beethoven just because there “are” suggestions of African beats in his music. Creative tendencies might be genetic and instinctive, but artistic composition and performance is not.

It is sheer racist baloney to assume certain characteristics, such as “rhythm” and “emotion”, among some ethnic groups while attributing others, such as “symmetry” and “reason”, to others. I am as African as Kilimanjaro and the Nile, but you will not find a speck of rhythm in me!

In any case, it would not be such a big deal if Beethoven had African ancestry. He would not be the first great European artist to be so connected. Russia’s best-loved author, Alexander Pushkin, had an Ethiopian grandmother, as I learnt from an insightful thesis by one of my first MA students at the University of Nairobi, Joyce Njoki Murango.

Even Aesop, the classical fable-maker, is believed to have been black, his name being a version of “Aethiops”, the Greek for black. Incidentally, that is where Leopold Sedar Senghor got the title, Ethiopiques, for one of his latter poetry collections.

Yet I was taken aback by the vehemence with which Beethoven’s “blackness” was asserted, and denied in equal measure, in the online debate. It just goes to show that racism is alive and well and it is difficult to avoid being tainted by it.

In any case, it is impossible to ignore the frequency of fatal police “mishaps” involving black people in the greatest land of the free. All the way from Texas to Maryland, where some of my closest relatives live, being black still seems to be a matter of life and death!

Anyway, it all started with my listening to music. How much do you listen, and to what kind of music? I am voracious. You may remember my telling you I am exclusively a consumer (although I tinker around with keyboards when no one is listening, and I love tapping on the bicycle-wire keys of my marimba thumb-piano in the privacy of my room).

But when it comes to listening, I spare nothing, whether it is indigenous home fare, ancient Gregorian church chants, classical compositions, country, jazz, gospel, hip hop, reggae, raga, rap, bongo flava or anything in-between. It is all grist for the mill of my audio delights.

The trouble with many of us is that we confine ourselves to just one or two of the infinite varieties available all over the world, especially in this day and age of “streaming” and YouTube. This is unjustifiable self-denial. If we can take the naughtiness out of “Franco” Luambo Luanzo Makiadi’s song, for which he was actually imprisoned, we can say it is sousalimentation musicale (musical malnourishment).

DRAWN TO THE SOUND

Speaking of Lingala music, one of my favourite real-life stories is of one of the sweetest voices I ever heard in Nairobi. I had just arrived on an overnight Akamba bus and I was resting in a room in one of those downmarket lodgings in Latema Road, where the washbasins and other facilities are just across the corridor outside the rooms.

Then I heard it, an angelic voice crooning, a capella: nkombo nayo nkombo nangai, nkombo nabiso; nkombo nayo nkombo nangai, ebongi toyokana. Suddenly, I felt a strong urge to dash out of the room and see the source of that voice, and I did. The singer was a youngish woman of rather nondescript frame and features, but I was glad to have seen her.

I understand a little Lingala, picked up on a short course at Makerere in the early 1970s. So, I could make out that the lyrics of the young woman’s song were suggesting that, since the honour of her name and that of her partner were inextricably bound together, they should always act in harmony. But it was not the “meaning” that had drawn me out of my room. It was the sound.

When I use this story to illustrate the importance of sound, or euphony, in literature, the invariable question my students ask is, “What happened next?”

My answer is, predictably, “That’s not part of the story.”