Author reveals the agony of being a refugee at Dadaab

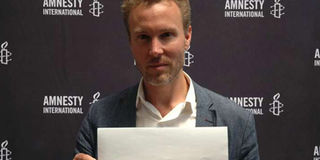

A chat with British author Ben Rawlings, who wrote ‘City of Thorns’ on life in a refugee camp. PHOTO| QAABATA BORU

British writer Ben Rawlence’s latest book, City of Thorns, is the first ever to be written on the Dadaab refugee camp. It documents the day-to-day lives of nine Somali refugees and their families in what is arguably the world’s largest refugee camp located in northeastern Kenya.

I met up with the former politician, who spent years working as a Human Rights Watch activist when he was in Nairobi at the invitation of Amnesty International. He spoke about his book and the global refugee crisis.

What struck me about your book is its simple descriptive language and the picturesque nature of the prose. Did you consciously decide to write it so?

Yes, it was very deliberate. When one is writing a non-fiction book, usually there is politics to it because one always wants to communicate a message, highlight an issue or draw attention to something, and, therefore, one has the moral obligation to make the book as accessible and as readable as they can.

I want to talk to people and make them care about the issue of refugees. So, the vivid style and the descriptions are supposed to draw the readers in.

Is Kenya doing enough to help the refugees in Dadaab?

Yes. Kenya is helping the refugees by giving them a safe space within its borders. That’s the minimum the refugees could ask for. However, the restrictions on work and freedom of movement are actually psychological as well because the refugees are then unable to hope, plan or make a life for the future. Kenya could do more if it does away with the encampment policy.

How has the coming of social media changed the way life is lived in Dadaab.

Social media acts as an amplifier of pre-existing tensions. Already everyone in the camp is very jealous of all their friends, who have been relocated to the USA and Europe. Through social media they can see images of their friends’ lifestyles abroad. Of course, the images are exaggerated. On the other hand, social media facilitates communication and thus relatives can stay in touch and send money.

Both refugees at Dadaab and those resettled elsewhere have formed close-knit social media groups.

Tell us a little about what you say in your book about the politics of bread in Dadaab

In Dadaab, the price of anything is hunger and your food is your currency. The refugees have to trade off their food rations in order to get money for other wants. Towards the end of the book, one of the subjects, Guled, is malnourished because of ration cuts. As he and other refugees watch Al-Jazeera, they can’t help but realise that the reason for the food ration cuts is because the rations are going to Syria.

That’s the global politics of food. There is also the local politics to it because the ration cuts are permanent now and the refugees’ think that this is pressure that is directly related to their repatriation to Somalia.

You haven’t put pictures of the refugees or the camp in your book. Why not?

Our culture has become too reliant on images and it gives people the illusion of understanding where, in fact, there’s only reorganisation. I think the only way people can find out the truth is by reading a story of someone who has lived there. As such, I felt putting pictures would enhance stereotypes that already exist about the camp.

Why the interest in human stories? First Radio Congo and now City of Thorns?

I’m interested in the world, in why things happen and how people respond to difficult situations. I’m also interested in trying to engage with those problems and writing is my way of doing it. I tried politics and human rights activism but neither of those was entirely satisfying to me. I feel more comfortable and useful talking to these people and telling their stories rather than engaging in messy stories of parliament in London or global advocacy.

How has the repatriation directive changed the daily life in Dadaab refugee camp?

Life is much harder in Dadaab now because the directive sowed confusion. The UN has gone silent, the Kenya Government hasn’t told refugees what is going to happen after November so they are imagining bulldozers and soldiers will be sent to the camp. There is panic and so this means that markets are closing, shops are shutting, agencies can’t hire or plan because the UN has told them to pack up by November.

Kids and teachers are staying out of school and donors aren’t funding Dadaab because they think it might close. As a result there is rising hunger, malnutrition and diminishing funding for education.

Most Western writers have been accused of introducing the shock element by painting grotesque images of Africa. Did you consciously think of this matter while writing your book?

The problem with writing about Dadaab refugee camp is that it is the living embodiment of all of these stereotypes that the West has manufactured and fed on for decades. Nonetheless, the reality is shocking, so I didn’t need to exaggerate anything. Also the obligation of a writer is to present the truth as they see it.

So, yes, I was very conscious that I was writing a book about a place that fit Western stereotypes and I hope I did succeed in painting a true picture of the place and creating characters, who have both complexity of character and individuality. I could have exaggerated and made it more shocking, but what I decided to focus on was the daily lives of these people.

What right do you have to write this story?

If a Kenyan had written the story already, then there would be no need for this book. It would even have been better if a refugee had written it. Unfortunately, the society as a whole chooses not to think or engage deeply with refugee matters.

From your experience living and working in Dadaab, do you agree that it is a nursery for terrorists?

Actually, I don’t think so because at the camp one encounters people who were raised under the umbrella of Kenyan safety, love Kenya, wear bracelets with the Kenyan flag and even sing songs about Kenya. Actually, a lot of them hold moderate religious views because they are mostly Sufi pastoralists from the south of Somalia and not from cities. Majority of them came in the 1990s, when they were fleeing a country where women didn’t cover themselves, went to discos and even wore bikinis to the beach. Yes, Al-Shabaab passes through Dadaab, yes you can trace phone calls to Dadaab, yet you can say the same thing of Nairobi, Garissa, Mandera, London, and Stockholm.

A UN security guy I quote in my book says that it is hard to do anything sophisticated in Dadaab because everything is in blocks where everybody knows each other and there is a community peace and security team and a neighbourhood watch, and the residents watch out for strangers in their blocks because they don’t want to get in trouble with the Kenyan police. Also, these people are quite nervous about their refugee status because they don’t want to be sent back to Somalia where, if Al-Shabaab finds anyone with food ration cards, they execute them for taking food from infidels.

As such, these refugees have absolutely no incentives to cooperate with Al-Shabaab.

Is there any good that can come out of hosting refugees in a country?

Actually yes. Refugees can be assets to a country. What Jordan and Ethiopia are doing is using the refugees as bargain chips in a positive fashion.

For example, Ethiopia is bidding for $500,000 in World Bank funds in exchange for a right for refugees to work and then they’ll build factories and both refugees and Ethiopians will work there.

This means that the Ethiopian Government creates employment and gets cheap labour from the refugees with cheap capital from the World Bank. It is a win-win for everybody.

Kenya can also do the same and use the refugees to leverage the World Bank money and build factories and create Special Economic Zones in the northeastern region or in Kakuma.

Gloria Mwaniga is a teacher and author based in Baringo County.