My up and close encounters with Uganda’s literary greats

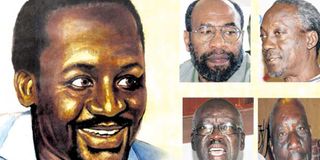

From Okot p’Bitet to John Ruganda. Timothy Wangusa and Okello Oculi the literary scene in the Pearl of Africa since the colonial days to the disruptive dictatorial regime of Idi Amin has never been dull place. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- And what would John Ruganda have said about a year ago, when his pet name, 'Araali', was made a Unesco World Heritage Property? Well, 'Araali' wasn’t recognised in isolation but along with 10 other endearment names, called empaako, of which every member of the Bunyoro-Kitara and Toro communities must have one.

- I was at Makerere when Ruganda and the Ngoma Players group did a pre-publication performance of 'The Burdens', and later of 'Black Mamba', in which my friend Richard Arden starred as the womanising, hypocritical English professor, but I was not directly involved.

- Ruganda had brought his Nairobi University Free Travelling Theatre group (which I think included the current Makueni Governor, Prof Kivutha Kibwana, then a young student) to perform for us at the school, and he gracefully decided to stay the night. Okot p’Bitek, too, and the “Ugandan-Malawian” poet David Rubadiri graced my Machakos house with an overnight visit.

Okot p’Bitek’s Song of Lawino has just been translated into Luganda, as Omulanga gwa Lawino. It is a grand homecoming for the great poem, after wandering through more than a score of different languages.

Per pa Lawino has linguistically just crossed from the northern to the southern bank of the Nile. What would Okot have said about this, I wonder.

And what would John Ruganda have said about a year ago, when his pet name, 'Araali', was made a Unesco World Heritage Property?

Well, 'Araali' wasn’t recognised in isolation but along with 10 other endearment names, called empaako, of which every member of the Bunyoro-Kitara and Toro communities must have one.

In Ruganda’s home town of Fort Portal, at the foot of Mount Ruwenzori, a monument was unveiled recently, inscribed with 'Araali' and all the other 10 empaako.

FAILED RELATIONSHIPS

Speaking of mountains, recently when I was in Mbale, eastern Uganda, the kadodi drums were announcing the arrival of the imbalu (circumcision season) that will for several months envelop the Bamasaaba cultureland, from Kamonkoli to Webuye and beyond.

I recalled the 1972 season, when Timothy Wangusa, a son of the Mountain, and several of us, his colleagues from Makerere, crisscrossed the area, recording, photographing, filming and interviewing the basinde (circumcision candidates), the bakhebi (surgeons) and other elders, documenting the fascinating “dance to manhood”.

Wangusa is the author of several volumes of superbly beautiful poetry and of the acclaimed “poetic” novel, Upon This Mountain, about the experience of growing up and “facing the knife” around the Elgon in the colonial period.

Wangusa became a lot of great things, including Professor of Literature at Makerere, Minister of Education, first Vice-Chancellor of Kumi University in the Teso region, and Presidential Adviser on Literary Affairs, a post which I think he still holds.

Some critics claim that Wangusa’s novel was inspired by our research experience in the 1970s, but this is not true.

Wangusa told me the story and about his intention to write it way back in 1969, when we were housemates at Makerere, “caretaking” the bungalow of our University Secretary, who was on study leave.

We were young tutorial fellows then, in the Department of English, Wangusa had just returned from Leeds after his Master’s degree and me from Dar es Salaam, after a failed relationship, which put paid to my intentions to settle there permanently.

My new acquaintance was an excellent antidote to my self-pitying melancholy. He never failed to amuse, with his conspiratorial chuckle and his impeccable English accent, into which he effortlessly blended anglicised Lumasaaba words, like “mwogos” for “rogues”.

Wangusa belonged to the class of 1964, which included such literary greats as Okello Oculi, Micere Githae Mugo, and the drama gurus Rose Mbowa and John Ruganda.

Mbowa and I had, in our pre-university days, been protégés of Byron Kawadwa, the eminent Luganda dramatist and theatre director later murdered by Idi Amin.

I am humbled, even today, by the fierce loyalty, or maybe even platonic love the late Rose Mbowa had for me. As Associate Professor of Drama, she struggled tirelessly through the administrative tangles to make Makerere reinstate me, when few even knew who I was, after a break of over 20 years.

She had to fight an equally tough battle to persuade me to leave my comfort zone in Kenya and plunge into the harsh realities of “post-liberation” Makerere. She got me there, but she never quite got me to leave Kenya!

As for John Ruganda 'Araali', our early meetings were rather formal. He probably had acted in my play, 'The Secret', performed by the Makerere Free Travelling Theatre, when I was away in Dar es Salaam.

OVERNIGHT VISITS

We were introduced to each other by David Cook, when John was the Oxford University Press representative in Uganda. I was later to have that hilarious episode of directing him for television as Jero in Soyinka’s Trials.

I was at Makerere when Ruganda and the Ngoma Players group did a pre-publication performance of 'The Burdens', and later of 'Black Mamba', in which my friend Richard Arden starred as the womanising, hypocritical English professor, but I was not directly involved.

Anyway, John soon fled the Idi Amin terror and started anew in Kenya, where we were to re-connect. But it wasn’t in Nairobi, where I was later to become a regular performer in his Nairobi University Players productions, but at my beloved Machakos Girls High School humble abode.

Ruganda had brought his Nairobi University Free Travelling Theatre group (which I think included the current Makueni Governor, Prof Kivutha Kibwana, then a young student) to perform for us at the school, and he gracefully decided to stay the night.

Okot p’Bitek, too, and the “Ugandan-Malawian” poet David Rubadiri graced my Machakos house with an overnight visit.

They and their colleagues from the University of Nairobi had come to run a workshop at the Machakos School for literature students from schools in the area, and I had taken my girls to participate and meet the literary greats.

My former Makerere colleagues were so delighted to find me in Machakos they decided to cross over for a chat at my house. We picked up some drinks as we crossed the town, but I can’t remember what we did for food!

LAST LAUGH

Who cared anyway?

Soon we were chatting away into the wee hours of the morning, recalling and reliving our old bohemian Makerere days, and reminiscing about our colleagues who were now scattered all over the world.

My most vivid recollection of Okot in Machakos is of him stretched out before my fireplace, shivering with a fever, and laughing at this maskini mwalimu, who didn’t have even an old blanket to cover the bones of his old guest.

I imagine Okot would have welcomed Abasi Kiyimba’s brilliant Luganda translation with his mischievous hacking laugh and asked if Lawino would now have to learn how to eat Kiganda matooke with Acholi malakwang sauce. Okot could never stop laughing, at everything and everybody, most frequently at himself.