A very humbling award and the women who got it right

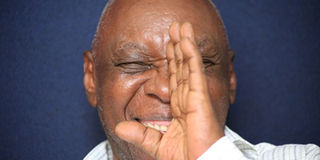

Prof. Austin Bukenya who was declared the winner, out of six nominees, of the prize for “service and achievement in the arts and humanities”.The citation said I had contributed significantly as a writer, a researcher in oral literature and an academic. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- Though only an honorary member of the women’s club, I have always been an active participant, and this time I had a special role at the conference. Since “Mother Hen”, our Founding President, the Honourable Mary Karooro Okurut, was away on ministerial duties, I was to deliver the opening speech.

- Most importantly, however, these enterprising women got it right by actualising the realisation that writing matters and, especially, that the woman’s voice has to be heard through the printed word.

- There they declared me the winner, out of six nominees, of the prize for “service and achievement in the arts and humanities”.

Winning an award, whether an Oscar like Lupita Nyong’o’s or for being the neatest pupil at school, is a thrilling experience. I should know, as for nearly a week now I have been reeling from the tumult of emotions that accompany such an unexpected happening.

Maybe telling you about it will help me sort out my confusion. I should not, however, pretend that I am resisting the temptation to brag about the surprise recognition. I readily admit the pride and the “swagger”.

It all started with a phone call, asking if I was Bukenya, and I said yes. Such calls are routine in our line of work, and they are usually from aspiring graduate candidates seeking advice about vaguely formulated research proposals.

But the caller last week had a startling invitation for me. I had been nominated for a lifetime achievement award and could I, please, attend the awards dinner at the Protea Hotel on Friday evening?

That was only two days away, and my attention was in any case focused on a literary conference at Makerere University’s School of Women and Gender Studies, where my FEMRITE (the Uganda Women Writers Association) sisters and I were celebrating the 20th anniversary of our existence and achievement. I am a founding member of FEMRITE, as I never tire of boasting.

Though only an honorary member of the women’s club, I have always been an active participant, and this time I had a special role at the conference. Since “Mother Hen”, our Founding President, the Honourable Mary Karooro Okurut, was away on ministerial duties, I was to deliver the opening speech.

PRINTED WORD

After all, I had been there in 1996 when it all started, sharing with Ms Okurut an office along what, I think, should be renamed the Ngugi wa Thiong’o Corridor in the Literature Department. It was, indeed, off this corridor, endlessly trodden by greats like Ngugi, John Ruganda, Micere Mugo, Timothy Wangusa and many others before and after them, on their way to their “staple” Lecture Room Four, that FEMRITE had been hatched.

In my humble remarks to the conference participants, I suggested that FEMRITE meant women who write, women who got it right, women who claimed their right and women who were, that morning, performing a rite. FEMRITE women set out to write and they are still writing, with vigour and distinction, 20 years on. Apart from their impressive list of publications, the sisters have earned sterling international honours, including the Caine Prize (Monica Arac de Nyeko) and the Commonwealth Literature Prize (Doreen Baingana).

All this is in addition to global recognition through invitations to collaborate with high profile world performers. Among these are the Feminist Press of New York, who co-opted FEMRITE members into their “Women Writing Africa” project and also published some of their works, like Goretti Kyomuhendo’s novel, Waiting, alongside other East African greats like Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye.

Kyomuhendo has herself gone on to head the African Writers Trust, based in London, while her former colleague, Dr Mildred Barya, has embarked on an academic career in creative writing at the University of North Carolina. So, FEMRITE seems to have got it right by deciding to organise Ugandan women to write.

Most importantly, however, these enterprising women got it right by actualising the realisation that writing matters and, especially, that the woman’s voice has to be heard through the printed word. FEMRITE is thus an iconic assertion of the woman’s right “to be, to do, to grow, impact”, as I put it in my poem “W-woman”, appropriately dedicated to FEMRITE.

Those, then, were the “rights” and “writes” that FEMRITE was celebrating at a rite of re-evaluation and re-dedication to what we started 20 years ago. We had a star-studded audience, which included eminent scholars and writers from all over Africa, among them our own Ken Walibora, South Africa’s Prof Pumla Dineo Gqola and 90-year-old Sarah Ntiro, one of the first six women students to join Makerere in 1944.

I would have thoroughly understood if my award had come from FEMRITE.

But no, it came from NACOBA, the Namilyango College Old Boys Association. Now, Namilyango College is the oldest high school in Uganda. Launched in 1902 by the English Mill Hill missionaries, it predates by several years the other two citadels of Uganda’s elite education, the ladies’ Gayaza High School and the most famous Kings College, Budo, David Rubadiri’s and Charles Njonjo’s alma mater.

THIRD FEELING

I am a proud ‘Ngonian (Namilyango alumnus), having done both my “O” and “A” Levels there, but I am ashamed to confess that I have never been active in the Old Boys Association activities. Indeed, I have hardly been back to the school compound, only 20 kilometres outside Kampala, since I left, except for a few desultory visits to my old headmaster, Ben Kuipers, who was still charge, shortly after my graduation from Dar es Salaam in 1968.

But apparently Namilyango and my “OBs”, as we familiarly call our fellow alumni here, have kept track of all my doings and misdoings. So, I had to hearken to their summons to me to attend the NACOBA awards dinner. There they declared me the winner, out of six nominees, of the prize for “service and achievement in the arts and humanities”.

The citation said I had contributed significantly as a writer, a researcher in oral literature and an academic. I could hardly believe my ears. Was that really me they were lauding?

Anyway, as I collected my colourful trophy, three main feelings were running through my head and mind. One was that people do notice what we do, provided that we do it with sincerity and dedication. Secondly, I vowed that I should immediately become active in NACOBA, to avoid being “humiliated” again by undeserved recognition.

The third feeling was of gratefulness that I, and all my “OBs”, had never been tempted to burn down our beloved Namilyango (house of many “milango”, entries). Where would my award have come from if we had?