Three of the best: Celebrated writers on the good and bad of Africa

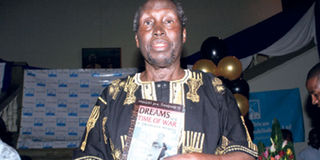

Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o. The second instalment of the Kenyan author’s memoirs, In the House of the Intepreter, explores Africa’s inability to rise from poverty, disease and ignorance. File/Photo.

What you need to know:

- Which mother — for Africa has always been seen as ‘motherland’ when its political landscape remains dominantly fatherland — can leave her child to the vultures, crows and locusts, such as Soyinka refers to above?

“The children of this land are proud/But only seeming so/They tread on air but – Note – the land it was that first withdrew/From touch of love their feet offered/once, it was the earth of their belonging/Their pointed chins aimed/Proud seeming, at horizons filled with crows/The clouds are swarms of locusts.” (Wole Soyinka. ‘The Children of this Land’)

Is Africa cursed? Is Africa fated to war; drought; hunger; starvation; bad governments; decay; death? Is Africa, the supposed birthplace of humanity, predestined never to join the world human family?

These are old questions. They were being asked in the early 1960s as several African countries were given flag independence by their colonial masters. Yet these questions remain nagging today, 50 years or more after that independence, for a majority of African countries.

As another half-century rolls on, it is time for Africans to reflect, deeply, beyond the accusations against their former colonisers. It is time for serious thought on how to take the continent forward, not just politically or developmentally but also in how Africa treats its own children.

Which mother — for Africa has always been seen as ‘motherland’ when its political landscape remains dominantly fatherland — can leave her child to the vultures, crows and locusts, such as Soyinka refers to above?

But to rethink Africa, to renew it, to launch it into the 21st century or even to register in the community of other nations, peoples and cultures, Africa has to look at and into itself; Africa has to be honest with itself, engage in serious introspection and seek to remove the log in its eye rather than continue to engage in recrimination about colonialism, neocolonialism and globalisation.

It is for this reason that this first column, ‘The Books of the Month’, picks on Ngugi wa Thiongo’s second instalment of his memoirs, In the House of the Interpreter (2013), Chinua Achebe’s There Was a Country (2012) and Wole Soyinka’s Of Africa (2012).

Probably, let’s try to see Africa, once more, from the lenses of the creative writer rather than the hundreds of treatises by political scientists, economists, anthropologists and policy makers. To debate Africa as if it is a single entity is, at times, an act of gross oversimplification.

Africa is very vast geographically. Its hundreds of languages and cultures can be very confusing. Its climate is very varied — people die of heat in Cairo but are frozen in winter in Cape Town.

But the continent, too, does have shared cultures that cross the colonial-designated borders and which should allow us to see it as an entity, indeed. Add to these factors its colonial heritage and its immersion in globalisation and your problems when trying to understand it are multiplied a hundredfold.

Yet Africans have spent the better part of half a century since the end of colonialism complaining about how destructive colonialism was to the continent. Apparently, this shedding of tears happens without much irony.

Africans, from its leaders to its intellectuals to the civil society, down to the ordinary people on the streets and slums of its cities, all the way to the peasants in the villages are obsessed with the narrative of colonialism, neocolonialism, imperialism and other ‘isms.

Africans appear to be conveniently reluctant to honestly debate what colonialism brought to Africa and what Africans themselves have done to the continent and what can realistically be done to help the continent out of its misery.

Reading Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s In the House of the Interpreter reveals a lot about what Africa could have done with the good that colonialism brought and what it could have done with the bad it introduced as well. Ngugi’s book is about his time at Alliance High School.

It is a narrative of his youthful innocence, discovery and dreams — the ‘dreams’ that he speaks of in the earlier volume of the memoir, Dreams in a Time of War. It is a story of a boy who finds security and comfort in the school compound, terrified of what would happen to him when he leaves the gates of the school. Out there is a war between the Mau Mau and the British soldiers. One could be game for either party.

But Ngugi’s book is also an ode to Carey Francis; that enigmatic school teacher and empire builder who dedicated his life to producing civilised subjects of the Empire at Alliance. Ngugi paints Carey as a legend; as a man who “… saw Alliance as a grand opportunity to morally and intellectually mould a future leadership that could navigate among contending extremes ….”

Here was a white man who wished to nurture the best of minds from among all the Kenyan communities, in the hope that this group of young men (and women) would pilot the country into a better future.

Yet many years after the inauguration of this multicultural ideal, Kenyans are still grappling with such illusive and elusive notions as ‘national cohesion and integration.’ The disturbing question, one that should probably be asked to Ngugi and his schoolmates of those many years ago is: what happened to the multi-cultural and cosmopolitan project that Carey Francis planted at Alliance School? What happened to the nascent spirit of equality, peace and unity that Ngugi paints in In the House of the Interpreter?

Ngugi says this of Alliance and Carey Francis: “Right from the start, Alliance’s national spirit was contrary to the state’s policy of dividing Africans along ethnic lines, and the school accepted students from different communities.

But under Carey Francis, recruitment into Alliance on a countrywide basis became a consistent policy in theory and practice. North, central, east, west, and southern coastal Kenya were all represented on the Alliance compound.

Most important, the African staff came from different Kenyan communities and were revered or reviled purely for their individuality, not for their ethnic origins” (Interpreter, 96).

So, if some adventurous mzungus could clearly see that the future stability of the country depended on how egalitarian its institutions would be, why are we still debating inequality in the sharing of the ‘national cake’?

Did Ngugi and his generation fail to acquire the best of the ethos of the interpreter? Indeed, can’t one suggest that the presumed ethnocentrisms of Kenyans today can directly be attributed to the failure of the pedagogy offered even in the elite schools like Alliance?

Well, a terrible consequence of the maladjustment of the African to the colonial ethos was the Biafra War of secession; a war that symbolised the worst in the marriage of the imperialists and the new African elite.

There was a Country leaves no doubt that it is a eulogy to the dream of the Biafrans to break free from the republican Nigeria. It is an unequivocal celebration of the Igbo people. Achebe writes of the Igbo as special; as naturally endowed intellectually and environmentally.

He laments the refusal by the Nigerian nation-state to accommodate the Igbo and exploit their talents as one of the reasons it is seen as a failed state today.

He writes, “The Igbo were not and continue not to be integrated into Nigeria, one of the main reasons for the country’s continued backwardness, in my estimation.”

Yet Achebe’s memoir demonstrates that the war of secession, like many such wars in Africa, left millions of the Igbo and other Nigerians worse off than when it begun. Who ever was held accountable to the more than two million Nigerians who perished in the war? Indeed General Yakubu Gowon and Emeka Ojwuku retired to live and probably have coffee not so far from each other.

Achebe could be paying tribute to the Biafra cause but can there really be a just war? Think of the ceaseless uprisings in Congo DR; or in the Sudan. How many of these wars are really justified?

How many of them aren’t merely the results of greed by a few local leaders? What was the difference between Ojwuku and Gowon? Did the Nigerian federalists really differ ideologically from the secessionist Biafrans? Probably yes; probably no, although on a balance, the no would tilt the scales.

So, how do we interpret Africa’s problems today? How do we begin to have a parley on the solutions to these problems beyond the cliché ‘local problems, local solutions’, an edict that hasn’t worked in donkey years. The old man of the African theatre, Wole Soyinka, offers some suggestions on how to think afresh of Africa’s problems in Of Africa.

Of Africa is a clarion call to Africans to use the past to re-examine their present.

Part I of the book, ‘Past into Present’, establishes what Soyinka calls the ‘fictioning of Africa.’ The first is driven by the “adventurers”; the second by “commercial” interests; the third he calls “… internal, power-driven fictioning” by the successors of the first two; and fourth derives from “… cross-continental exchanges between Africa and her diaspora.”

The first two ways of ‘seeing and talking about Africa’ are charged to the history of European, Arabic and other adventurers into Africa and the colonial project. That is how the idea of the ‘dark continent’ emerged. The third is self-inflicted. This is about incorrigible African leadership.

Such arguments like ‘Africa is unripe for democracy’ or ‘only Africans themselves can find solutions to their problems’ or ‘the so-called civil society or pro-democracy activists are lackeys of the West’ etc, which are meant to justify dictatorship and bad governance and only add value to the prejudice about Africa as a hopeless continent.

Soyinka warns that even more damaging could be those who seek to speak for Africans out there. He suggests that the consequences of the search for amends for Africa, from the former colonisers, can be insidious because “… the danger is that in pursuit of this agenda, an Africa that never did exist is created, history is distorted, and even memory is abused.

An argument for Reparations between aggressor and victim can still survive evidence that the victim side was not completely innocent in its own undoing — be it through negligence or direct complicity.” Here is a call for tact, in the way Africans talk about their experience of exploitation and suffering from colonialism, neocolonialism and globalisation!

Moving beyond the history of prejudice against Africa and Africa’s suffering, Soyinka suggests, in the section he calls ‘Body and Soul’ that Africa’s redemption could be found in ‘The Spirituality of a Continent.’ He calls for a ‘back to the roots’ of the continent’s spirit of egalitarianism, which was/is best epitomised in the many religious/spiritual practices on the continent.

He deliberately juxtaposes ‘Africa’s spirituality’ to other religious practices from Europe and Asia (Christians and Muslims won’t like this argument), and argues that African spirituality is naturally democratic, with the gods not claiming any supremacy over humankind.

If we rekindled this spirit, Soyinka suggests, we would achieve, at the least, two ends. First, we would offer the rest of humankind a spirit of change for the better in a world that largely knows only pain and suffering, caused largely by religious dogma. Second, Africa would begin to recover from the trauma of colonialism and the post-colonial debauchery of its leaders.

But why are these three books, or theses, important for us? Ngugi reminds us of the evil of colonialism but by highlighting the achievements of Alliance School, Ngugi underlines an aspect of colonialism that Africans have failed to adopt and adapt to seriously.

On the other hand, Achebe introduces the enigma of the tension between the colonial-instituted nation-state and the various nations that found themselves bounded by the imposed geographies and governance structures.

Soyinka, on his part, is asking Africans to look more keenly unto themselves and see what is good within them that could be used to initiate useful and productive change on the continent.

Tom Odhiambo teaches literature at the University of Nairobi. [email protected]