Chimamanda: I owe it all to Achebe

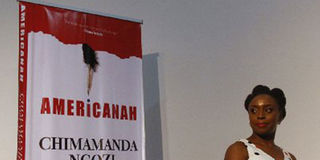

Literary sensation Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie was recently in Nairobi for the Kwani? at 10 celebrations, where she pulled enthusiastic crowds wherever she went. PHOTO/EMMA NZIOKA

What you need to know:

- I don’t think anyone should think about writing thinking I want to write because I want to become rich. It is not going to happen.

- There are times you want to write and it is not happening. So I like to call it the spirits are not speaking to me. But there are also times the spirit speaks to me, so you want to write; you have this rush.

- My position is that I am a Pan-African, I am Nigerian, I am Igbo; I am equally all of those things. I am not going to deny one for the other. I am Igbo because my perception of the world was very much coloured by being raised by Igbo parents; going to an Igbo village many times a year.

- I am not a world citizen. I don’t know what that is. I have a Nigerian passport; I don’t know what a world citizen is.

What’s your feel of Kenya today?

I don’t think it has changed.

I like Kenya. I travel quite a bit. I have been to many places.

Sometimes you just land in a place and there is a sense that you get. And it is the kind of thing that you can’t explain.

But it is the sense or the feeling that you are welcome; you are at peace. I have always felt it in Nairobi. I am also hopelessly Pan-African, so I have a kind of romanticised affection for sub-Saharan Africa.

But because I haven’t visited all the countries, I have it particularly for Kenya because I have been to Kenya. Just even looking at the airport, looking at the Kenya Airways, I am so moved. It is very silly and romanticised, but it is also true feelings.

Q: The ‘Pride of Africa?’

A: Yeah, I saw that. And there is also something about it.

Look, I can put on my cynical cap and say ooh, there is so much that can be done, what is there to be proud about, but on the other hand we can argue about what 50 years means in the lifespan of a nation, and when we look at many of the countries on this continent, because we love these countries, and that is where we are, we are alive today, we are very annoyed that they are not doing well.

But when you look historically, they are very young; it is not that surprising. Nation formation takes a very long time.

Yeah, a 50-year-old person isn’t quite old.

But a 50-year-old person isn’t a nation. Let’s look at nations that we think have sort of formed the idea of the nation. Let’s look at how long it took them; how many of their people they killed...

So for me, I have had the moments where I almost despaired. I never despair anymore. I am just thinking there is so much potential; we can do better.

Q: The writing and the bank account. How do they relate?

A: They have no relation.

Q: Are you making money out of writing?

A: Why is it ok to ask a writer if they are making money? If I worked as a banker or an advertising executive would I be asked that?

Absolutely no.

So why is it acceptable to ask me that?

Q. Because it is an old question that has refused to go away.

A. No. The reason that this question bothers me is because I didn’t start writing because of money.

I don’t think anyone should think about writing thinking I want to write because I want to become rich. It is not going to happen.

When I started writing, I was writing and I was also thinking: what am I going to do to earn a living?

Writing is what I loved, but on the other hand, I thought I am going to get a job. So I started off thinking I was going to be a doctor.

Then I left medical school because I was unhappy. Then I was going to do media; I was thinking I can do public relations, advertising, radio, TV; and all of those things I could do so that I can earn a living and then write.

People always ask: is it worth writing if I can’t make money out of it?

The question then is: do you want to write because you want to become rich?

If the answer is yes then you better go and become a banker. If that’s the reason for writing then forget it.

Q. What’s the relationship between inspiration and work ethic in your case?

A. I think you need both to write.

There are times you want to write and it is not happening. So I like to call it the spirits are not speaking to me. But there are also times the spirit speaks to me, so you want to write; you have this rush.

But it is also work. I mean there is the craft of it. I am a hard worker. I am an obsessive reviser. I write and rewrite constantly. And I think that actually sometimes in writing, it is not really the writing that is hard, it is the rewriting.

In my own process of writing I, am obsessive and very focused.

Q. What about your work schedule; say from a Monday morning onwards, when the spirits have visited?

A. Ooh, when the spirits are visiting, I don’t do anything else.

So, it means on a Monday morning I pull out of bed; I don’t shower; I am in front of my computer; when I am eating I am in front of the computer.

I feel as though I don’t want to miss any minute of it. And the thing that is wonderful about it is that I get so absorbed when I look up I realise so much time has passed.

There are times when I stay very late, till 3am and I wake up at 9am and I want to go straight back to the writing.

I don’t want to do anything else. I don’t pick up my phone. So, usually when the writing is on, my family are often concerned and they say to me: just send us a text to let us know you are fine.

Q. You are in another world?

A. Yeah. But not even to make it that mystical, I think that writers are different. In my process I just need to have that kind of focus.

And it is not that I am writing all those hours. There are times when I stop to dream. There are times when I stop to read.

Q. Do you think a writer can be trained to write creatively?

A. Yes. I think you can help a person improve their craft. But you will not be able to give a person the story to tell.

There is something that you need to bring to the process. The people who come to my workshop already have something. And my role is to sort of say to them: think about moving this paragraph; think about telling the story in retrospective rather than in the present, that kind of thing.

That is what you can teach them but there are things that you can’t. So, somebody who has no… I don’t want to call it innate talent, but that is really want it is… or a kind of longing for storytelling or ability, if you don’t have it and if you feel like you must write, it is not going to work.

Q. Is it like the wandering disease in Cyprian Ekwensi’s Burning Grass? Do you need to catch a bit of sokugo to write?

A. I think most creative people have a measure of madness. Writers are different.

There are writers who don’t want to travel at all and there are those who want to journey.

I think the fundamental thing is what I like to call the ‘longing in your heart for storytelling.’

Q. What is Achebe’s abiding legacy for you?

A. I don’t know. Whenever I am asked to reduce something to one thing, I never know. Chinua Achebe is the writer whose work is most important to me.

That’s really the only thing that I can say. If Chinua Achebe hadn’t written his books, I don’t think I would be where I am.

And I don’t think I would have told my stories in the way I did when I did.

Q. Why?

A. Because when I read him, he gave me a certain kind of confidence; he gave me validation.

There are certain things you read and it just means something to you and not just because on the level of craft, story and plot, but simply because there is an emotional connection. Aaahh, he gave me permission.

Q. What of the mothers of African literature: Flora Nwapa, Buchi Emecheta, Ama Ata Aidoo, Grace Ogot etc in relation to Achebe?

A. I love those women; I read them after him.

Q. You read Joys of Motherhood after Things Fall Apart …?

A. Much long after. And it is actually not Things Fall Apart but Arrow of God, which I love.

Q. Back to Achebe. There has been a perception that there existed tension between the departed patriarch and Wole Soyinka.

A. I don’t think that that is true. I think it was an invented tension.

Q. By critics, journalists …?

A. By other people who were not involved.

Q. But what do you have to say to Soyinka’s supposed claim that Achebe shouldn’t have written ‘There was a Country?’

A. I don’t know. I am always careful about this kind of thing. I don’t think I saw that interview.

If you look at Wole Soyinka, I am not sure that that is what he meant. Wole Soyinka wrote The Man Died in prison.

Wole Soyinka has said consistently that Eastern Nigeria was very much justified in seceding and forming Biafra.

He has said from the beginning that there were injustices committed. So, it is not as if he is an apologist for killing people in Biafra.

And he knows what his contemporaries who were in Biafra went through. In other words, he has always been sympathetic, as I think any right-minded person would be.

So, it is not about taking sides, it is about looking at the facts of history. I think it is a shame that Chinua Achebe’s book was so badly misunderstood, often by people who can’t read.

Q. Say a little more on that.

A. Many people who hadn’t read the book had opinions on it.

Q. That’s quite usual.

A. Yeah, but it is very stupid. And then it becomes a controversy. I am not going to become one of those people who will say, ooh, Soyinka was very terrible when he said that about Achebe.

Because for me it is also about: ‘look at what a person has stood for.’ And that interview was conducted by Sahara Reporters as I understand it; Sahara Reporters are problematic.

Q. Problematic?

A. They are problematic because they are always looking for the sensational.

They sensationalise everything. So, it is not about calm; looking for truth. It is about what is the most shocking thing we can do and if it means slightly moving things to make it very sensational, they will do it.

So, for me, if Sahara Reporters is the source of something, it immediately means I look at it with half an eye.

Q. So, what do you have to say about ethno-nationalism in Nigeria?

A. It is not an atavistic thing that has always been there. It is something that is created and can be re-created.

My position is that I am a Pan-African, I am Nigerian, I am Igbo; I am equally all of those things. I am not going to deny one for the other. I am Igbo because my perception of the world was very much coloured by being raised by Igbo parents; going to an Igbo village many times a year.

It is different from my sister-in-law, who is Yoruba.

And those cultural things are things I value: the Igbo songs, the Igbo folklore that I want to preserve because I think it is important.

I think the problem started with… what colonialism did. One of the terrible things is that it made us to think that in order to build the nation, and push the white man out, we had to forget; we had, somehow, to pretend that we are not Igbo; we are not Yoruba because the nation means that we are now all Nigerians.

We say that in English, but we go back to our homes and we speak Igbo; we eat Igbo and Yoruba foods, right? My thing is: I want a leader in a country like Nigeria, in a country like Kenya... with a different orientation.

If we had a president in Nigeria, who is an Igbo man, what he needs to do is to get the best from every part of the country.

What we have now is a situation where our leaders always surround themselves with people who are like them… you know, you go to your village and you get all your ministers from there and everybody else feels excluded.

And that is what makes people start retreating to their own little enclaves, really. If you have a leader who is not denying that he has a village and he likes his food in his village but he is also saying: we are Nigerians, we are all Nigerians and my ministers come from wherever…

And you don’t get them because they are from the North; you get them because he is the best and he happens to be a northerner; he is very good and he happens to be a southerner.

If we got that in Nigeria today, tribalism would reduce considerably.

Q. There is an overpowering feminine spirit in your work.

A. Is there an overpowering masculine spirit in Achebe? In Soyinka? In Ngugi? Ayi Kwei Armah? Is there?

Q. An African author or a world citizen of letters?

A. I am not a world citizen. I don’t know what that is. I have a Nigerian passport; I don’t know what a world citizen is.