Breaking News: At least 10 feared to have drowned in Makueni river

Guru once dreamt of becoming a taxi driver

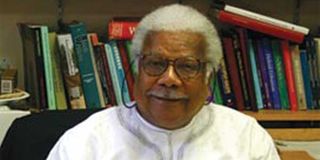

Prof Ali Mazrui, who was a globally acclaimed scholar of history and economics.

What you need to know:

- I was anxious about my encounter with the renowned scholar, partly because of an overwhelming awareness that although I had been living with the idea of him— Ali Mazrui the scholar, I was going to meet Ali Mazrui the person.

- This curiosity started at an early age when his childhood dream was to become a taxi driver so that he could travel and meet different people from different places and different cultures.

- Mazrui spoke truth to power, challenging authoritarian policies wherever he could find them.

“If, at the end of time, I will be asked what I did with my life, I hope I will have spent most of it creating a rainbow world or making contributions towards it; a world guided by considerable acceptance of multiculturalism, tolerance of differences and dissent, and acceptance of diversity,” Ali Mazrui told me in one of my last interviews.

For I had the privilege of being Ali Mazrui’s authorised documentary biographer, tracing his life from his birthplace in the East African coast, to his residence in New York.

My first meeting with the doyen was at a time when I was designing a model, which sought to examine the implications of a restrictive information environment on a nation’s collective memory, especially when documents containing a country’s past are destroyed, distorted or inaccessible.

We met during the annual African Studies Association conference in Chicago in 2008.

I was anxious about my encounter with the renowned scholar, partly because of an overwhelming awareness that although I had been living with the idea of him— Ali Mazrui the scholar, I was going to meet Ali Mazrui the person.

Inside his hotel room, I noted copies of several bookmarked texts on his desk.

There were brown envelopes with manuscripts he was editing.

On his bed lay a small radio, which I later found out he carried wherever he went.

GIFT OF LANGUAGE

“I received this radio as a birthday gift on February 24, 1966. As I listened to it, I heard Kwame Nkrumah had been overthrown. He was toppled on my birthday,” he said, making me feel at ease in his presence.

As we sat by a coffee table next to his desk, I noted he had my name hand-written on the first page of his white writing pad.

We talked for more than one hour. And as I listened to his experiences growing up, the intellectual trajectory of his legendary contributions, reflected in the apparently inexhaustible passion for the controversial, it became clear that his life and work offer an insightful narrative of East Africa.

What I remember from our first meeting is Ali Mazrui’s ability to listen and his capacity to hear what is being said as well as the undercurrent of what is being said.

When you couple that with his exceptional gift for language, you encounter an intellectual who was able to articulate what had been said with greater clarity.

He always knew the right words to produce the desired effects: to stimulate the imagination of his listeners and readers.

As I followed Mazrui during the filming of the documentary, I came to appreciate his genuine curiosity whether engaging with undergraduate students, young scholars at conferences or policy makers and heads of states in boardrooms.

He always took notes because “I am always learning,” he said.

This curiosity started at an early age when his childhood dream was to become a taxi driver so that he could travel and meet different people from different places and different cultures.

And although he never had a driver’s licence, he traversed and gave lectures across the globe, meeting iconic legends such as Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King, Jr, controversial figures such as Muammar Gaddafi and Louis Farrakhan; boxing legends such as Mohammed Ali; political activists such as Malcolm X; and political dictators such as Idi Amin.

As a product of colonialism and its cultural and educational institutions, Ali Mazrui understood Europe very well, and powerfully articulated issues rooted in Africanity using a language that is comprehensible to the West.

His role, therefore, became that of a translator of Africa to Europe, and Europe to Africa; a bridge-builder who for more than half a century, consistently challenged dominant European ideas and images of Africa in very powerful ways.

LEADING VOICES

When Mazrui came to Makerere from Oxford in 1963, he became one of the leading voices in the discourses that were taking place in East Africa. This was the period when the line between politicians and intellectuals was not clearly marked.

Presidents Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Milton Obote of Uganda often had arguments with Mazrui, and these arguments would be published in journals such as Transition as well as in daily newspapers.

Mazrui, therefore, became a model of what intellectuals do: being influential in shaping national and public debates.

But what made Ali Mazrui an exceptional scholar is his active participation in producing and enriching a form of scholarship that provided a global view of Africa, especially at a time when it was very tempting to retreat to parochialism.

Mazrui opened up debates about Africa to other influences; not only the relationship between Africa and the West, but also the place of Islam in African societies.

Notwithstanding critical voices about his triangulated theory of the convergence of three heritages — African, Islam, and Western— it is increasingly being appreciated that Islam cannot be ignored in Africa and that as long as African knowledge is produced on the margins, it will not have the influence it should globally.

Because of Mazrui’s prodigious output, reputation and personality, he was able to become an influential player in major institutions across the globe.

Mazrui spoke truth to power, challenging authoritarian policies wherever he could find them.

I once asked him over coffee what we didn’t know about him: “I have always wanted to write more fiction and poetry in both English and Kiswahili. I am a frustrated novelist.” He intended to write a novel with a Maasai Pope as the chief protagonist.

When we met in Binghamton to celebrate his 80th birthday, he paid tribute to his friend the late Dudley Thompson, a renowned Jamaican lawyer, who was the defence counsel during the trial of Jomo Kenyatta in 1952/53.

LESS COMBATIVE

“Like his father, Uhuru Kenyatta has been accused of instigating violence. But instead of a British colonial court, which charged the older Kenyatta, we have the ICC charging the younger Kenyatta.

The older Kenyatta was unjustly imprisoned by a colonial court, but the younger Kenyatta is unlikely to be found guilty by The Hague. Unfortunately, Dudley Thompson is not alive to be counsel for the defence of Uhuru Kenyatta,” he said.

This was typical of Ali Mazrui’s brilliant and dialectical mind, which allowed him to neatly weave seemingly irreconcilable contradictions, powerfully uniting opposites as a method of illuminating reality.

Although he had to be accompanied by a health escort in his final years, and that his voice was less resonant, he continued to give lectures across the globe, attracting large audiences.

The delivery of his speeches was also slower but still reflective and poetic. He continued to command attention and his arguments pulsated with unbridled creativity.

With age he became less combative but maintained his curiosity. He grew a beard, acquiring a contemplative look of a sage. And his modest bag still contained some of the most recent publications.

His life was one long debate and his pen was eloquent. In our last interview he had an interesting request: “You will let me know when we meet in AfterAfrica if other scholars continued to use the triple heritage model after I am gone.”