‘God from machine’: Miracles do happen even in Swahili fiction

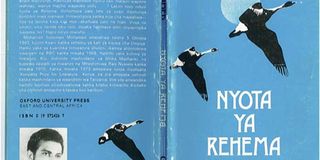

Nyota ya Rehema is a novel by award-winning Zanzibari writer, M.S. Mohamed. PHOTO | NATION

What you need to know:

- Deus ex machina is Latin for ‘God out of machine’. In ancient Greek and Roman drama, a god (the statue of a deity or an actor) could be introduced by means of a contraption such as a crane to decide the final outcome; to unravel and resolve the plot.

- John Habwe’s ‘Ungamo la Janaha’, a short story in the Takrima Nono collection, edited by Clara Momanyi and Rayya Timmamy. Kembo is accused of robbing and raping a widow, mama Jerida.

Writers use conflict to build interesting plots. One is the internal conflict where a character experiences two opposing emotions; the archetypal struggle between right and wrong. The other is external; between a protagonist and an antagonist.

Conflicts are vital elements of a storyline; geared towards achieving a goal or resolution, to entertain or for moral lessons. When conflicts are at their peak we are at the climax; on tenterhooks, awaiting a plausible solution. It is an anticlimax when an implausible concept or divine character is introduced into the storyline to resolve the conflict. When such a scenario happens, the writer or narrator has used the deus ex machina device.

Deus ex machina is Latin for ‘God out of machine’. In ancient Greek and Roman drama, a god (the statue of a deity or an actor) could be introduced by means of a contraption such as a crane to decide the final outcome; to unravel and resolve the plot.

This device of solving a crisis by divine intervention was used widely by Euripides, the Greek tragedian. In modern usage, it refers to a plot device where an insoluble problem is suddenly resolved by the contrived and unexpected intervention of some event or character.

Sometimes a writer ends up with a complicated storyline. Having painted himself to a corner, nothing short of a miracle can help untangle the mess. It is deus ex machina if a sudden and unexpected solution to a state of chaos is provided by devices external to characters and activities within the story.

Deus ex machina is not peculiar to Greek and Roman drama. Shakespeare used it. Nor was it confined to dramatists; Charles Dickens used it too. There are several examples in Swahili literature as well.

LACK OF CREATIVITY

It has been used by John Habwe’s ‘Ungamo la Janaha’, a short story in the Takrima Nono collection, edited by Clara Momanyi and Rayya Timmamy. Kembo is accused of robbing and raping a widow, mama Jerida. His character does not point to him carrying out such heinous acts. Yet when accused, he acquiesces; meek as a sheep. He is sentenced to life in prison. Ten years later, word trickles to Kombe’s parents that he is ailing as a result of being sodomised. Out of the blue, Kemu, Kombe’s cousin confesses to the crime. The mystery of who was the villain has been resolved through a character whom the author had not developed.

In Timothy Arege’s Mstahiki Meya, we meet a despot per excellence who brooks no dissenting voice in his fiefdom; Cheneo town. Using his minions, the mayor deals ruthlessly with his opponents. Eventually a strike leads to the cancelation of a visit to the town by some delegates; there is also fear of a cholera outbreak due to a biting water shortage. The mayor’s chief adviser deserts him, his personal assistant also joins the strike. Life is grinding to a halt. All of a sudden, the mayor is arrested at the behest of the ‘headquarters’. All along, as he runs the city to the ground, this ‘higher authority’ was never mentioned.

Nyota ya Rehema is a novel by award-winning Zanzibari writer, M.S. Mohamed. Rehema is destined for hardship. Her father banishes her mother to the farm after disowning his daughter. When her mother dies, Rehema goes to live in her father’s homestead. She runs away from mistreatment, ending up in prostitution.

When she finally settles with Sulubu, trouble comes in the form of her half-sister’s husband who grabs the farm. She again starts afresh but the brother-in-law again tries to grab their second home. Sulubu kills him in a fit of rage. The subsequent murder case ignites a revolution which saves Sulubu from the hangman’s noose. He is saved by an event external to the plot; deus ex machina at work.

There’s criticism galore for this literary device. It is deemed undesirable in writing as it implies a lack of creativity on the part of the writer. Resolution to a conflict should arise internally. Characters should be developed not merely introduced to resolve a conflict. But is it always a weakness?

In Mstahiki Meya, the introduction of the central government at the end of the play signifies that the government is totally removed from the problems of its citizens.

Sometimes the oppressed behave like a volcano, building up pressure beneath the surface. Eventually something triggers a violent reaction, the way Sulubu’s murder case triggered a revolution in Nyota ya Rehema.

Deus ex machina therefore can be used, though sparingly. Miracles do happen, even in fiction, but they are rare.