New book sheds light on apartheid-era surgeon who caused Kenya big heartache

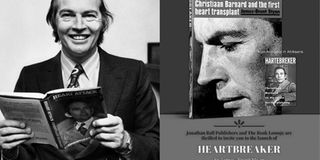

This file photo taken on May 2, 1972 in London shows South African surgeon Christiaan Barnard posing with his book during a press conference. On the right is the book Heartbreaker: Christiaan Barnard and the First Heart Transplant which will be launched in South Africa on Tuesday, December 5, to mark 50 years since the ground-breaking procedure. PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The world’s first heart transplant came about as the result of a twin tragedy on December 3, 1967. First, a 25-year-old woman Denise Darvall had been involved in a terrible road accident that had left her brain-dead.

- At the same time a 54-year-old man, Louis Washkansky, was in hospital literally dying from heart disease.

A newspaper reporter has published a new book on Dr Christian Barnard, the South African surgeon who gained global acclaim when he performed the world’s first heart transplant in 1967.

Heartbreaker: Christiaan Barnard and the First Heart Transplant, will be launched in South Africa on Tuesday, December 5, to mark 50 years since the ground-breaking procedure.

Written by James Styan, the book covers the life of South Africa’s most famous surgeon, from his childhood through his studies at home and abroad to his prominent marriages – and divorces.

The writer also “examines the impact of the historic heart transplant on Barnard’s personal life and South African society at large, where apartheid legislation often made the difficulties of medicine even more convoluted.” Barnard died on September 2, 2001, in Cyprus.

The world’s first heart transplant came about as the result of a twin tragedy on December 3, 1967. First, a 25-year-old woman Denise Darvall had been involved in a terrible road accident that had left her brain-dead. At the same time a 54-year-old man, Louis Washkansky, was in hospital literally dying from heart disease.

Faced with this possible double tragedy, Dr Barnard, then an audacious 45-year-old surgeon at Cape Town’s Groote Schuur Hospital, took the initiative to transplant Darvall’s heart into Waskansky’s body. While this only enabled Washkansky to live a further 18 days, it catapulted the surgeon into instant worldwide superstardom.

That dashing surgeon, who gained fame through his pioneering medical work and notoriety for his much-publicised affairs and marriages, also managed to cause a split in President Jomo Kenyatta’s Cabinet.

This unwitting excursion into high-level Kenyan political intrigue came just over a decade after his ground-breaking operation. The main characters in the drama were the left-leaning, anti-apartheid Foreign Affairs minister, Dr Munyua Waiyaki, and the pro-western Attorney-General, Charles Njonjo. Mr Njonjo was thought to favour what would later be referred to as a policy of “constructive engagement” with the apartheid government of South Africa.

ARRIVED AS NJONJO'S GUEST

According to information gleaned from a number of sources including the diplomatic cables from the US Embassy, which were published by WikiLeaks, the controversy came about when Dr Barnard arrived in Kenya on May 13, 1978, for a week-long visit as Mr Njonjo’s guest, following Dr Barnard’s successful heart surgery on an eight-year-old Kenyan girl in South Africa a few months earlier.

While in Kenya, Dr Barnard made a number of public appearances and gave interviews in which he stated his total opposition to the apartheid system, despite having been described as his country’s “best ambassador” by a former South African Prime Minister (1966-1978) John Vorster.

'NO DIFFERENT FROM OTHERS'

Barnard also addressed medical staff at the Kenyatta National Hospital and controversially said that Kenyans should ignore hostile propaganda against South Africa. He said his country was no different from others which practised discrimination on the basis of race, religion or tribe but were spared the vilification that South Africa was subjected to.

Speaking to members of the Rotary Club later, Dr Barnard called on Kenyans to visit South Africa and “see for themselves” how things were. Mr Njonjo, who also spoke to the Rotarians, expressed the hope that Kenyan doctors and businessmen would take the opportunity to visit South Africa — this despite an official travel ban on Kenyans visiting South Africa. The ban was manifested in a stamp in all Kenyan passports that allowed the holder to visit every country in the world except South Africa.

When Mr Njonjo fell out of power and out of favour with President Daniel arap Moi a few years later, it was claimed during the Commission of Inquiry into his dealings that the former AG had skirted the travel ban a number of times to visit the then pariah nation.

During his visit it, was rumoured that Dr Barnard had been briefed by Vorster and told to make friends with his Kenyan colleagues and help build a friendship between the two countries.

If Dr Waiyaki was already upset that his ministry — which was in charge of Kenya’s hardline anti-apartheid policy — had not been consulted over the controversial visit, he was furious that Dr Barnard was making such statements in Kenya. The minister made it clear in a statement to the press that he was totally against the visit and questioned why it had been made at all.

In the spirit of Cabinet responsibility and not wanting to appear to be taking on his fellow Cabinet colleague, Mr Njonjo, head on, Dr Waiyaki authorised ministry official to speak to the media and state: “We detest the fact that Barnard appears to be speaking for his country’s Foreign minister (Pik Botha at the time). We reject his (Barnard’s) statement that any hostile campaign against South Africa’s unacceptable policies is unjustified.”

The foreign affairs spokesman also restated Kenya’s support for the UN and OAU position on South Africa.

Opinions in the media were divided over the Dr Barnard visit, with some commentators praising the surgeon and criticising his opponents as an “unenlightened minority who forget he is an outspoken critic of his country’s apartheid policies”.

In the middle of these exchanges, Dr Barnard himself appeared on the State-run Voice of Kenya (now KBC) television’s current affairs programme, Mambo Leo, to calm the troubled waters caused by his splash into the Kenyan political pond. He apologised to the President and people of Kenya for “any misunderstanding” that may have been created by the remarks he had made during his visit.

However, Dr Waiyaki was having none of it. He told a British journalist that he was “extremely annoyed about the Barnard visit”. According to him, Mr Njonjo had not consulted him but had only spoken about the visit to then Vice President and minister for Home Affairs, Mr Daniel arap Moi, who was in-charge of immigration.

A FURIOUS DR WAIYAKI

A furious Dr Waiyaki was reported as having said that by receiving Dr Barnard with open arms, Mr Njonjo was damaging Kenya’s efforts to implement a coherent policy against apartheid South Africa.

There had never been any love lost between the AG and the minister despite having some commonality in their backgrounds. Interestingly, both were from Kikuyu Town, both were past students of Alliance High School and ironically, Fort Hare University in South Africa.

Dr Waiyaki had in the post independence era aligned himself with the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga faction of Kanu that later broke away to form the Kenya People’s Union party. In fact, according to sources, Dr Waiyaki had been on the cusp of defecting to KPU when he was persuaded by old political friends such as Dr Gikonyo Kiano to remain in Kanu. In the 1990s, when multi-party politics made a comeback, Dr Waiyaki eventually defected from Kanu and joined Mr Odinga in Ford Kenya. Mr Njonjo on the other hand was the son of a colonial paramount chief and one of the foremost collaborators of British rule in Kenya. He had always stuck firmly in the pro-Western wing of Kanu and was close to Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

The then AG firmly believed that the anti-Barnard/anti-South African sentiment in the Kenyan media and among the political class had been whipped up by his political rivals — led by Dr Waiyaki — in an effort to embarrass him. These enemies included Dr Waiyaki’s predecessor as Kenya’s foreign minister, Dr Njoroge Mungai, and his nephew Udi Gecaga, who at the time was married to Kenyatta’s daughter Jeni. Udi was also the local chairman of the international conglomerate, LonRho, which owned the Standard newspaper where a lot of the anti-Barnard criticism was coming from that May.

During the visit, opposition to Dr Barnard also emerged in Parliament where MPs had planned to raise the question of the visit and about who between Njonjo and Waiyaki was reflecting the Kenya government’s views on apartheid. However, the legislators were at the last minute persuaded not to wade into the debate to save the government from further embarrassment.

Mwangi Githahu is a freelance Kenyan journalist based in Cape Town. [email protected]