Eyes on the prize: Kenyan film maker with a zeal that inspires

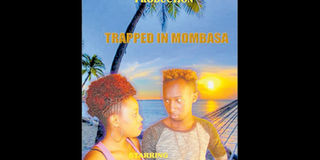

One of the movies that Kenyan filmmaker has Paul Njihia has made. I have not been able to recoup my expenses in both movies but that has not and will not deter me from making more movies because it’s a passion in me and I am optimistic enough that the movie industry in Kenya is coming of age soon-Paul Njihia, Kenyan filmmaker. PHOTO| KINGWA KAMENCU

What you need to know:

- In terms of quality, this was a film below par.

- Poor sound quality, bland sound tracks, unnecessary zigzagging about the city (including the characters taking a matatu from Kenyatta Avenue to Koinange Street — something both unreal and unnecessary), sound crew-men visible in the mirrors, lack of intimacy between the main characters, iffy dialogue and other minor details were some of the bloopers we found.

- The fact that the movie overtly aimed to give a moral lesson at the end did not help its case either.

Paul Njihia, a 47-year-old film maker born in Kiambu County, has quite a compelling story. After graduating with a degree in literature from Moi University in the 1990s, he left for the United Kingdom at the first opportunity he could get to study film at City University, London.

Njihia, who left Kenya in 2000, is now back. He resides in Kenya, although he returns to England from time to time. To date, he has three movies to his name: Coming to England (2009), Malaika (2016),) and Trapped in Mombasa (2017).

Inspired by a true story, Coming to England is a film about a jobless university graduate, Amani, who gets the ‘opportunity’ to go to England to live with her aunt. Once there, however, she quickly discovers that the streets are not paved with milk and honey as she had imagined. She has to do menial jobs, including cleaning toilets, to survive. Amani later mixes up with ‘wrong company’ and finds herself on the wrong side of the law.

UK-based Kenyan film maker Mr Paul Njihia. He is determined to change the Kenyan movie scene.

KINGWA KAMENCU | NATION

There were unfortunate aspects about the movie, including the use of foreign accents by the Kenyan actors, in an attempt to portray sophistication (in truth, nothing makes one look more backward). Happening even way before the main character had stepped out of the country, one would sometimes find the actors beginning their sentences with British intonations, only to end up with American twangs.

In terms of quality, this was a film below par. Poor sound quality, bland sound tracks, unnecessary zigzagging about the city (including the characters taking a matatu from Kenyatta Avenue to Koinange Street — something both unreal and unnecessary), sound crew-men visible in the mirrors, lack of intimacy between the main characters, iffy dialogue and other minor details were some of the bloopers we found. The fact that the movie overtly aimed to give a moral lesson at the end did not help its case either. There was a time such loose threads could be overlooked, but today, the standards of local TV shows and movies have risen so much that they are almost on a global level.

Happily though, things were not all terrible with Coming to England. The matatu scene before the club was brilliantly shot, with the loud music, the flashing lights and the makanga hanging from the door adding to the authenticitiy. The scene with the urchins on the street was one of the best in the film, the street urchins being full of a energy, making this one of the most vivid scenes of them all.

The plot of Coming to England is not too bad either. What worked best about it was the manner in which it gives a true reflection of how life is for Kenyans who have recently migrated to the West. It depicts the taking on demeaning jobs even for people who were senior in Kenya, and their slow and arduous climb to the top. Set between England and Kenya, Njihia must be applauded for doing the undone and going to shoot beyond Kenya’s borders.

His other films Malaika (about a girl picked up from a rubbish dump and brought up by a man and woman of the streets) and Trapped in Mombasa (revolving around a girl, Furaha, who goes off to college at the Coast and falls into its wicked ways) are just emotionally unengaging with a few monotonous scenes, poor soundtracks and occasional wardrobe malfunctions.

This former high school teacher had submitted Trapped in Mombasa for the 2017 Riverwood Awards which took place two weeks ago but it did not make the shortlist. This is not surprising given the issues of poor sound, poor soundtrack and wardrobe issues, where it fell short. While Njihia’s strength is in his understanding of story outline and plot structure, his downfall is in the execution of the details. He would do well to remember the words of the iconic American producer of the 60s, Orson Welles: “A writer needs a pen, an artist needs a brush but a film maker needs an army.” To up his game in future, Njihia needs to do a few things.

First, he needs to look for a professional acting crew the next time he is doing his movies. He can find actors on varied platforms such as actors.co.ke and Kenya Actors Guild (KAG). Second, his movies will do better with original scores, or at the least, music sourced from local musicians to make the soundtracks.

He will find that by enlisting these, he will have also have found himself a free marketing team as they will eagerly share the news of their work with their fans and audiences, which will then translate to higher sales of DVDs or tickets in the cinema hall.

NEEDS SCRIPT-WRITING WORKSHOP

Third, given that Njihia writes his own scripts, he needs to attend a script writing workshop to learn how to write stories bereft of didactism and moral lessons. Cajetan Boy, Ubuni Media and the Kenya Scriptwriters Guild hold occasional screenwriting workshops and he can easily find any of them via social media. Njihia should also take a peek at this year’s Riverwood Award winning feature film Kizingo, to see what a movie that aims to simply entertain for the sake of entertaining looks like.

We would give Njihia a D for the quality of his movies, but an A for effort, which rounds off at an overall C+. It is inspiring to realise the relatively large sums of his own money that he has put into his productions and the determination with which he continues to plod along. He spent Sh1.2 million on Coming to England and Sh750,000 on Trapped in Mombasa, all made with money from his savings.

“I have not been able to recoup my expenses in both movies but that has not and will not deter me from making more movies because it’s a passion in me and I am optimistic enough that the movie industry in Kenya is coming of age soon. I see the future as bright for the movie makers and actors in Kenya.”

While in London in the early turn of the century, Njihia set up his own security company. In Kenya he also runs real estate and farming enterprises, from which he gets the capital to bankroll his filming endeavours. “I’m starting to become serious with films from this year. I want to have done four more by the end of this year.”

If a man goes into business to support his artistic endeavours, you can be sure that a lot more will be coming out of his stable. That, and the gleam in Njihia’s eye, makes us know that even though his current productions have not been top ranking, he is nevertheless still a film maker to keep one’s eyes on.

Interested parties looking to engage Njihia or buy his movies, will find him launching Trapped In Mombasa and Coming to England on April 8, at Zetech University, off Thika Super Highway, Ruiru.