Literary icon who did much more than analyse folk tales

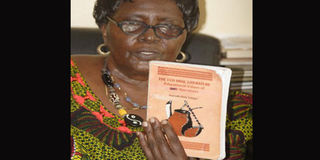

Bespectacled, with an ever smiling face and hardly discernible lisp in her speech, Asenath Bole Odaga was a composite of personalities — a scholar, anthologist, novelist, children’s writer, lexicographer, dramatist, archivist and entrepreneur. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- The formal entry of oral literature into the school syllabus in 1982 was, for Asenath, a milestone in reclaiming our identity and the value of our culture.

- When Taban Lo Liyong visited Kenya in 1989 and resurrected his pet topic of literary barrenness, Asenath was categorical in her rebuke, observing that Taban was probably talking about literary barrenness in Uganda (his adopted country).

- As we are wont to say, writers never die. Asenath’s legacy remains not only to continue educating us but to inspire the pursuit of cultural authenticity, creativity and literary enterprise.

When Chinua Achebe, the father of African Literature, died at the age of 82, one of my students remarked “the man was very old,” to which I retorted “literary icons are never too old”. This remark came to mind when I learnt of the demise of Asenath Bole Odaga at 80 years on December 1.

Bespectacled, with an ever smiling face and hardly discernible lisp in her speech, Asenath was a composite of personalities — a scholar, anthologist, novelist, children’s writer, lexicographer, dramatist, archivist and entrepreneur.

Asenath’s portfolio of literary works spans many genres, although she is probably best remembered for her pioneer 1982 text Oral Literature: A School Certificate Course (co-authored with Kichamu Akivaga), which was the mandatory text in secondary school oral literature for many years before younger entrants like myself came into the picture.

In this stable, Asenath also authored Thu Tinda: Stories from Kenya (1980), Yesterday’s Today: The Study of Oral Literature (1984), and Kenyan Folktales and Luo Sayings (1995).

The formal entry of oral literature into the school syllabus in 1982 was, for Asenath, a milestone in reclaiming our identity and the value of our culture. “In my initial research,” she observed, “people used to feel inferior about our oral literature”.

CULTURAL APPRECIATION

This changed once people realised that the study created cultural, academic and literary curiosity and was the foundation of our literary creativity and a prism for looking at and appreciating one another.

To her, learning each other’s oral literature could reduce ethnic prejudices, promote tolerance and, ultimately, forge nationalism. Because of the centrality of oral literature in awakening cultural awareness, Asenath maintained that the merger of Literature and English in the 8-4-4 syllabus was a regrettable step since oral literature would be scaled down. In her view, this was an experiment not worth undertaking.

Her only solace was that at university level, most literature students preferred African literature to the other units although she also believed that a good literature graduate must be grounded in literature from elsewhere so as not to be parochial.

Asenath believed, contrary to many classical academics, that pop music is oral literature. “Pop music is ideal literary entertainment for both the literate and illiterate,” she said. “It must be developed because it is pop music now but becomes the reservoir of classics in history”.

She also believed that the fact that oral literature was increasingly being written did not reduce its “orality”. It only helped to preserve it.

Furthermore, she considered it the moral duty of African publishers to champion their own hence her investment in the Lake Publishers and Enterprises Ltd based in Kisumu, through which she published her own works.

Yet this was not merely a self-promoting venture as the publishing house also produced works for the Kenya Women Literature Group.

These include Min Nyiri gi Sigendni Moko (1990) translated into Ekegusi, Gikuyu, Luhya, Kitaita, Kalenjin, Maasai, Kikamba and Kiswahili, and Gimomiyo Otoyo Ng’ute Obam gi Sigendni Moko (1993) translated into English as Why the Hyena has a Crooked Neck and Other Stories.

For me, one of the most significant achievements of the publishing outfit was the republication of older works that had gone out of print such as Sigend Luo Maduogo Chuny by Shadrack Malo, Kar Chakruok mar Luo by Samuel Ayany and Sigendni ma Gaso Ji by L. Moore.

Together with this, the stocking of different works in Dholuo at her Thu Tinda Bookshop in Kisumu was a true testimony of her commitment to archiving our folklore and cultural wisdom.

NO DESERT HERE

When Taban Lo Liyong visited Kenya in 1989 and resurrected his pet topic of literary barrenness, Asenath was categorical in her rebuke, observing that Taban was probably talking about literary barrenness in Uganda (his adopted country).

“People write, there is theatre and theatre is no longer restricted to Nairobi as in the days of Taban,” she said. “Oral literature is thriving, or what is literature?

It does not mean that if Ngugi or Taban does not write then there is literary barrenness. We may not have produced an Achebe, but not every generation produces an Achebe.”

Nevertheless, Asenath acknowledged the dearth of literary works of merit in Kenya but related this to the lack of public appetite for creative works by local authors, the propensity of publishers to go for school texts and little disposable income which pushed parents to spend on material needs of life.

But she was optimistic since the society was still producing children whom she saw as potential readers.

Then the chair of the Kenyan Children’s Literature Association, Asenath believed that “we have to start with children reading for leisure to build a reading culture”. But if you thought she only believed in young readership, you are mistaken.

In fact, Asenath believed in a reading society, hence her opinion that retirees should write and share their experiences with adults and children alike.

An active population of writers would create an adequate corpus for libraries and bookshops to stimulate and sustain literacy, hence reverse the tendency she had noted that many Kenyans did not have a reading command of English, Swahili or vernacular.

When David Aduda eulogised Asenath, he hinted at her work on gender equality.

As he rightly observed, she was not polemical and demagogic about it but practical. In my encounters with her, Asenath believed in individuality before gender. Thus she did not consider herself an automatic voice for women’s concerns.

For her, a creative writer’s role remained that of representing reality and the society.

GENDER NEUTRAL

“To me there are no male or female writers,” she told me. “A writer is just a writer. In fact, if I was reading Marjorie Oludhe’s Coming to Birth and I was not told the author was a woman, I would not know or even mind. The fact that I am a woman does not bother me in what I do,” she told me in 1992 when I profiled her for New Age magazine.

But she would not be surprised if women created more literary works. After all, are they not the avant garde story tellers in traditional Africa?

Well, how else could she have proved that than the impressive collection of works she left behind? Sample her novels: Mogen Jabare, A Taste of Life, The Shade Changes, A Bridge in Time, Between the Years and Riana. Enjoy her Dholuo anthologies Poko Nyar Migumba, Nyamgontho wuod Ombare and Simbi Nyaima gi Sigendni Moko.

Then get into her children’s world with The Secret of the Monkey Rock, Hare’s Blanket, The Diamond Ring, Jande’s Ambition, The Villager’s Son, The Hedges are Falling, A Reed on the Roof, Block Ten and Other Stories, Endless Road, Atieno gi Onam, Nyange gi Otis and Something for Nothing.

Dramatise with her in Simbi Nyaima and Three Brides in an Hour. Document with her socio-cultural practices through Nyathini koa Nyuole Nyaka Higni Adek and Kisera.

Then crown it all lexicographically through English-Luo Words and Phrases and Dholuo-English Dictionary.

As we are wont to say, writers never die. Asenath’s legacy remains not only to continue educating us but to inspire the pursuit of cultural authenticity, creativity and literary enterprise. And dying at 80 years, if I were to answer my student, is a rather young age for such a trailblazer!

Or as my cousin Ng’uono always quips in funerals, “joma beyo ema tho to maricho ema dong” (It is the good people who die and the bad ones that remain). Psst…I am not one of the bad ones.

Okumba Miruka is the author of A Dictionary of Oral Literature, Encounter with Oral Literature, Oral Literature of the Luo and Studying Oral Literature