Muthama’s debut book takes a gloomy look at Kenya’s future

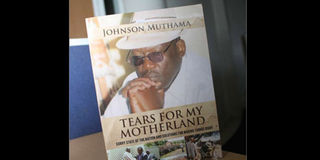

Nothing prepares you for Senator Johnson Muthama’s first novel. PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Muthama, marshals a fearsome array of stories and data to prove his point.

- Like a mortician, he succeeds in coldly and clinically observing and confirming for the readers what they have always feared, that Kenya is a heartbeat away from becoming a failed state mired knee-deep in corruption, tribalism and poor leadership that have then contributed to glaring disparities in the provision of education, health, water and food.

- To the potent mix, he adds rapacious multinationals out to grab Kenya’s natural wealth leaving us fighting while they repatriate the profits.

Nothing prepares you for Senator Johnson Muthama’s first novel, not even the foreword by his colleague in the senate, James Orengo, that raises expectations.

No holds barred, is the only way to describe Johnson Muthama’s debut novel, Tears for My Motherland. From the start, the reader is assaulted with a litany of maladies that afflict the Kenya. He devotes 12 out of the total 13 chapters to detail the “sorry state of the nation and solutions for making things right.”

The book is by no means autobiographical and neither does it provide an insight into the man behind the enigmatic politician hidden behind the ubiquitous dark glasses, posing pensively on the book’s front jacket.

The book opens with the introduction which, in a strange twist of events, serves as chapter one, too. The chapter details the runaway levels of inequality in the country from the time of independence flowing into the second chapter that suggests that a small elite are to blame for most ills and a courageous populace is required to take them on.

“One way of digging ourselves out of this hole is by being more courageous and speaking more energetically about the issues that concern us.” He then proceeds to narrate in no small detail how Kenyans will lose their country to the evil trio of “corrupt leaders, unscrupulous local business tycoons and international buccaneers.”

FEARSOME ARRAY OF STORIES

Muthama, marshals a fearsome array of stories and data to prove his point. Like a mortician, he succeeds in coldly and clinically observing and confirming for the readers what they have always feared, that Kenya is a heartbeat away from becoming a failed state mired knee-deep in corruption, tribalism and poor leadership that have then contributed to glaring disparities in the provision of education, health, water and food. To the potent mix, he adds rapacious multinationals out to grab Kenya’s natural wealth leaving us fighting while they repatriate the profits.

Describing himself as self-made businessman and patriot of the first order, Muthama is highly critical of policies and efforts that have so far been put forward to address these challenges. He also doesn’t bother to educate the reader how he arrived at his self-proclaimed sober and patriotic approach to politics.

What emerges is a book of detached observations devoid of emotion that would elicit any tears. It feels excruciatingly forced and stilted and reads like a collection of essays submitted by an overzealous student in partial fulfilment for an award or as a compulsory part of course work. With a meager sprinkling of anecdotes, Muthama narrates how important literacy is, using an example of a colonial guard who was to be whipped but was first required to take a note stating how many strokes of the cane he was to receive to the person that would cane him. The illiterate guard, faithfully delivered the instructions as ordered and received a sore backside for his trouble. He says this story was told to him by his father and remains the only insight into his personal life.

As of his businesses that have earned him international repute, he remains tight-lipped even if this was the whole premise of the book as promised in the foreword by Mr Orengo informing the readers that the book would be told from Muthama’s unique vantage point. The book, too, contains a collection of glossy photographs that offer relief from the depressing read. One, where the fiery politician had his pants torn in a scuffle in parliament appears in the collection as well as on the cover.

While Muthama lacks the elegance and pointed clarity of the seasoned writers, he makes up for it in anger, in righteous indignation and in exasperation presenting his own ambiguous solutions that have worked elsewhere and of which he is most certain can work miracles for this country.

He is particularly critical of the citizenry, whom he accuses of what he terms as a “collective surrender by Kenyans to the prevailing order of things”. He reserves the strongest part of the book to the denunciation of Kenyans who lack the courage to stand up for what he calls “their constitutionally guaranteed rights”.

As if the book is not gloomy enough, the ominously numbered Chapter 13, is reserved as the chapter of hope. Obama, the AU and other regional bodies, he writes, will not save Kenya. He gleefully talks of neocolonialism and tells us that we are on our own.

Luckily, the printer and the publisher saw to it that the pages in a few chapters were bound upside down, and that may be all the relief a lachrymose reader needs and who by the end of the book will be tearing up and wailing at the time lost never to be recovered.