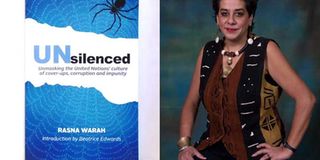

Rasna Warah’s book shines light on the problem with the UN

Rasna Warah’s book UNsilenced: Unmasking the United Nations contains a litany of such horrifying episodes, which only a former UN insider could have so succinctly catalogued. PHOTO | NATION

What you need to know:

- In typical Warah fashion, in her rather cleverly titled book, she does not beat about the bush regarding her mission, which is aptly explained by the book’s sub-title: ‘Unmasking the United Nations’ culture of cover-ups, corruption and impunity.’

- Warah’s narrative focuses on the carefully covered-up dry rot and scandals that reside within the corridors of the United Nations, and the fate of the men and women — usually referred to as whistleblowers — who from time to time attempt to reveal them.

- Citing specific cases of UN wrongdoing around the world, Warah once in a while pauses to, for instance, point out the impunity that accompanies the sexual exploitation of women and children.

Over the past couple of years, serious scandals have erupted in the international media relating to wrongdoing, serious corruption and even sexual misconduct in such international organisations as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

At the heart of the storm as these scandals unfolded were top figures like Paul Wolfowitz, who was at one time the World Bank’s president, but who was forced to resign after it was revealed that he had become involved in many malpractices, including barely veiled favouritism when it came to dishing out top positions at the organisation.

Yet another disgraced personality was former IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who was arrested and charged with sexual assault, attempted rape and unlawful imprisonment in New York after a widely publicised incident involving a female hotel room attendant.

In UNsilenced, her most recent book, Daily Nation columnist Rasna Warah delves into the murky world of widespread corruption and general malfeasance within renowned international organisations that spin doctors routinely depict as the world’s citadels of propriety, morality and virtue.

Warah’s narrative focuses on the carefully covered-up dry rot and scandals that reside within the corridors of the United Nations, and the fate of the men and women — usually referred to as whistleblowers — who from time to time attempt to reveal them.

GROSS MISCONDUCT

In typical Warah fashion, in her rather cleverly titled book, she does not beat about the bush regarding her mission, which is aptly explained by the book’s sub-title: ‘Unmasking the United Nations’ culture of cover-ups, corruption and impunity.’

Serious wrongdoings within global organisations have of course been catalogued in the past by people like Graham Hancock, whose 1990s classic book, Lords of Poverty, was a ruthless indictment of the UN and the entire development community around the world.

Warah cites other titles that have in recent years peeked into the darker recesses of specific organisations, including the UN, that the world rarely has a view of. Whereas many of the titles focus on documented scandals in top global organisations, including the UN itself, even more intriguingly, the authors take a close look at the woes that befall the few daring individuals who try to expose the rot in these organisations.

From Afghanistan to Kosovo, Darfur, Haiti, the Central African Republic and elsewhere, in Warah’s new book the shortcomings of the UN system are exposed with chilling accuracy.

For instance, after it was established in July 2014 that Central African Republic-based French peacekeepers operating under the UN Security Council’s authority were sexually abusing boys as young as nine, a quick cover-up operation was mounted.

As in many other cases relating to alleged wrong-doing carried out by individuals or entities operating under the aegis of the UN, the whistleblower in that case was a UN insider.

Named Anders Kompass, he was the director of field operations at the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. For his efforts, he was asked to resign, and when he refused to do so, he was suspended for “unauthorised disclosure of confidential information”.

Poignantly, Warah also enjoys insider status, having worked for 10 years as an editor at the UN Habitat office in Nairobi, which she left in a huff after inadvertently joining the league of whistleblowers herself.

Her whistleblower credentials aside, Warah also highlights other allegations of misconduct by UN peacekeepers in such countries as South Sudan, Côte d’Ivoire and Haiti, particularly between 2004 and 2006.

In these countries, which were in turmoil at the time, staff members from different UN bodies were accused of sexually abusing the same people they were supposed to be protecting.

Alarmingly, in 2005 alone, allegations about UN peacekeeping personnel having sex with minors stood at 60. In pointing out these crimes, Warah relies on documented evidence supplied by respected researchers.

Among them is renowned journalist Samantha Spooner, who in May 2015 published a scathing article on the subject titled ‘Sex scandals, food theft and weapons smuggling — what the UN wishes you didn’t know.’

HORRIFYING EPISODES

Another document cited by Warah is a report published in 2007 by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, OCHA. Titled ‘The Shame of War,’ the report analysed the crisis relating to the rampant sexual abuse of women and girls by UN peacekeepers and aid workers in war-torn countries.

Citing specific cases of UN wrongdoing around the world, Warah once in a while pauses to, for instance, point out the impunity that accompanies the sexual exploitation of women and children.

According to War, the most recent abuses took place in some of the world’s hotspots, including the DRC and the Central African Republic.

In Haiti, soon after the January 2010 earthquake that devastated the Caribbean island nation and left thousands of people homeless, the UN presence there was to prove disastrous.

During that year, Nepalese UN peacekeepers in the country were implicated for spreading cholera in the country. Although the consequent outbreak claimed more than 8,500 lives, the UN refused to take responsibility for it.

Rasna Warah’s book contains a litany of such horrifying episodes, which only a former UN insider could have so succinctly catalogued.

Intriguingly, the UN misconduct in Haiti led Chelsea Clinton, who visited the country at the time, to unleash a scathing attack on the perceived incompetence of the UN.