The harvest is great, we need literary critics

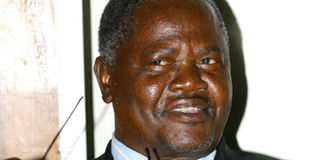

Prof Chris Wanjala during an interview at the University of Nairobis senior common room in this file picture. PHOTO | DANIEL IRUNGU | FILE

What you need to know:

- I did the East African studies touching on Ngugi, Taban, Okot, Leonard Kibera, and David Maillu, published in my two books, The Season of Harvest (1978) and For Home and Freedom (1980). I was a columnist with the Sunday Nation and a TV and radio personality.

- The more the changes took place at the University of Nairobi, the more sordid and draconic affairs of state became in Uganda. Taban lo Liyong, through Franz Nagel, the director of the Goethe Institut, had developed a cordial relationship with the German government.

- John Ruganda moved his family to Canada after obtaining a Canadian citizenship. He did his doctoral studies in Canada but returned to Kenya and joined the teaching staff at Moi University.

Taban Lo Liyong is now an old professor who travels from Juba to Nairobi to international book fairs and to launch his new books every year.

He enjoys literary debates with Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Ali A. Mazrui, the late Professor William Robert Ochieng’ and I. In most cases, William Ochieng, who died three weeks ago, and I bear the brunt of the debates, and we seldom answer back.

But now, in honour of my friend Ochieng, my reply to Mwalimu Taban lo Liyong will take the form of narrating the sequence of events involving all of us.

Taban wears a long white beard with a long grisly moustache. I have since these exchanges with him nurtured a beard to countermand his.

I first knew him when I was a young academic at the University of Nairobi and enjoyed a love/hate relationship with his writings. But now, with both of us getting advanced in years, we seem to be losing our balance.

In my culture, when you challenge a son to a duel and you learn that he is handling his weapons as dexterously as you do, you halt the fight and shake hands in appreciation of your son’s growth.

Taban has ruminated over what I said, and of course shot back, and created conditions for a truce. I am a grown up man now, but I can allow him to call me names as we part, knowing that he is the elder to whom I owe respect.

Taban is a great thinker, an essayist and wordsmith whose communication skills have greatly matured. He lives his life as a man of letters optimumly. If I had another life, I would reconcile with him because of his genius and industry as a writer. But now he has to keep his way as I follow the one I have charted for myself.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Okot p’Bitek, and Owuor Anyumba are Taban’s comrades-in-arms in their struggle to liberate literature from the hold of the West. They did for Kenya what Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Christopher Okigbo and John Pepper Clark did for Nigeria.

Ngugi’s genius could not blossom in the harsh climate of dictatorship and oppression in Kenya’s one-party rule. Of all the four, he was the man of the essay, drama and the novel. His impact, however, thawed in the poison-like Kanu regimes when he and his foot soldiers told the then powerful Attorney General that the Englishmen at the helm of the Kenya Institute of Education must leave with their curriculum that put English literature to the fore and African literature to the rear.

Ngugi’s future is in the white man’s country, wreathed in the mist of exile. We are the former young scholars at the University of Nairobi — William Ochieng, the true disciple and Bethwell Allan Ogot’s loyal student who wrote for the Sunday Post and the Sunday Nation as he studied the history of Abagusii, Elisha Atieno-Odhiambo who came from Alliance High School and Makerere University wielding his fountain pen as he commented on politics and wrote his poetry. Henry Mwanzi was our theorist who dabbled in Hegelian dialectics. We assigned him the study of the Kipsigis and prepared him very well for the Maasai studies, which he is doing today.

I did the East African studies touching on Ngugi, Taban, Okot, Leonard Kibera, and David Maillu, published in my two books, The Season of Harvest (1978) and For Home and Freedom (1980). I was a columnist with the Sunday Nation and a TV and radio personality.

Some people have said unwise, uncharitable and self-adoring things about us, but we have developed thick skins. We say in culture, every generation has its own songs. In the University College, Nairobi, days, when the Sierra Leonnian, Dr Arthur Porter, was the principal, you could count the number of creative writers from East Africa with the fingers on your two hands.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o had only his trilogy of prose fiction to his credit — The River Between, Weep Not Child, and A Grain of Wheat. For his drama, he had only The Black Hermit, a play which was a hot number in Uganda on the independence day celebrations. Today, librarians cannot cope with the number of books which are being released by publishers.

John Sibi-Okumu and David K. Mulwa are present-day playwrights who were also Dr Porter‘s and Dr Josephat Karanja’s graduates, respectively. Sibi-Okumu has authored more than six plays to date; David K Mulwa has more than 10. In the words of Sibi-Okumu, “Francis D. Imbuga wrote to his grave... and I would bet the Great Prefect has neither read nor seen any of them. There is enough for all of us to create, Prof. And I really think we do not give a good example to younger generations by fighting each other.”

The harvest is great; what we need are literary critics to pore over the products and report to us what they see in them. Prof Ochieng slipped out through the fingers of the East African intellectual scene almost in the same way Elisha Atieno Odhiambo, Aloo Ojuka, Henry Odera Oruka, and G.S. Were went.

For me, the death of Ochieng was a personal loss because he was the other general in the war against what Nuwa Santongo once called “stereo-typed pseudo-intellectuals.” Our struggle to reinforce intellectual life in Kenya is not directed at an individual. As Taban Lo Liyong said in 1969, in the East Africa Journal: “Knowledge about Africa can only be gained, as indeed knowledge on anything whatever, through hard study.”

The challenge that our generation is putting to you is that knowledge has a bigger picture than some of us may imagine.

Any bearded African who reads this and says it is maliciously directed to him would be claiming similar sins that he might have committed and therefore stands guilty as charged.

This country has created a home for many creative writers, artists, musiciams, dramatists, and literary critics as arrogant and self-opinionated as Es’kia Mphahlele of apartheid South Africa; to the extent that when I read Ghana’s Joe de Graft’s play, Muntu, or watch a production directed by the Sierra Leonian Janet Young, or visit Elimo Njau’s Paa Ya Paa Art Gallery which arose from Es’kia Mphahlele’s Chemchemi Cultural Centre, I do not feel that these people are foreigners in our midst.

I am so used to Okot p’Bitek and Theo Luzuka working with me at the East African Literature Bureau, Austin Bukenya, Cliff Lubwa p’Chong, John Ruganda, Elvania and Pio Zirimu, Charles Oluoch, Bahadur Tejani, Henry Kimbugwe, Esther Mukuye, Patroco Abangira (all Ugandans) and Gabriel Ruhumbika, Euphrase Kezilahabi, Ebrahim Hussein, and Florence and Francis Msangi (all Tanzanians) as my brothers and sisters in the literary fraternity that I do not see foreignness in them.

The three Ugandans who enriched the Institute of African Studies of the University of Nairobi include Taban Lo Liyong, Okot p’Bitek, and Francis Nnaggennda. No one discriminated against them. They complained more about the wildness of Idi Amin’s Uganda than the wildness of Kenya.

Taban, for one, was received with open arms and got a job at the Cultural Division of the Institute of Development Studies, which he could not get in Uganda. He subsequenly moved to the Department of Literature when the University College, Nairobi, became a full fledged university.

Before that, all African lecturers were called “Special Lecturers” whether they had doctoral degrees or not; Ben Kantai, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Fred Okatcha, Godfrey Muriuki and probably Taban Lo Liyong himself. They did not qualify to be lecturers because of their skins. White academics from Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa were given preferential treatment.

When Ngugi wa Thiong’o took over as chairman of the Department of Literature from Professor Andrew John Gurr, as the latter left the University of Nairobi for the University of Leeds, he was appointed by the central management of the university. He was not installed by Taban Lo Liyong as an individual. It is common knowledge that departments of English in Kampala, Dar es Salaam and Nairobi had British heads and it took them many years to believe that an African could head a department of English in a university.

University of Nairobi’s English department, with the campaign mounted by members of the Fourth Estate like Philip Ochieng, Awori wa Kataka and Christopher Mulei, drummed the need for change until it was accepted not only by the university management, but by senior professors like Bethwell Ogot, who was the Dean of the Faculty of Arts, and Simeon Ominde, who was the head of the department of Geography.

The more the changes took place at the University of Nairobi, the more sordid and draconic affairs of state became in Uganda. Taban lo Liyong, through Franz Nagel, the director of the Goethe Institut, had developed a cordial relationship with the German government. After a violent quarrel with the late Okot p’Bitek, his former teacher and fellow countryman, he left for Papua New Guinea. I met Taban at the FESTAC 77, Nigeria, where he had brought Papua New Guineans to participate in the cultural festival. He did not like the burgeoning nationalism in the Papua New Guineans. He wandered his way back to Africa through Khartoum.

Okot p’Bitek and David Rubadiri went to the University of Nsukka, Nigeria, as visiting professors. They came back to Nairobi famished and disillusioned. Although the politics of Uganda and Malawi had slightly improved for them, they were not psychologically ready to go back. At this time Okot p’Bitek was ill and more or less followed his personal physician who had moved to Uganda. Unfortunately his physician died ,and Okot p’Bitek also succumbed to his illness.

John Ruganda moved his family to Canada after obtaining a Canadian citizenship. He did his doctoral studies in Canada but returned to Kenya and joined the teaching staff at Moi University.

He did a stint there before moving to Swaziland and to the University of the North. No one can say John Ruganda was forcefully sent packing by the University of Nairobi. By the time Ruganda went to Moi University, I had long moved to Egerton University, where I founded the Department of Literature.

Ruganda died in Kampala in November 2007. Anyone who knew Ruganda and Wanjala will tell you that the two were great friends and were sometimes persecuted together.