The house at the end of history: The little city gem that is the Murumbi Gallery

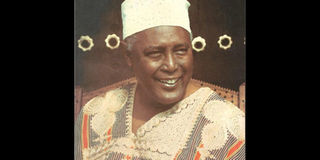

Murumbi, who died in 1990, was one of the more understated, if not scholarly, of all Kenyan deputies. His tenure ended in a resignation after Murumbi had been in the office a partly six months in office (May-December 1966). PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- While the building’s exterior appears scruffy, the interior is a revelation, and full of sun.

- To go inside is to walk into a miniature replica of Murumbis’ Muthaiga home.

- The living room is a window swung open, an invitation, and one would not be considered unbalanced to imagine Joe sweeping into the room any time, horn-rimmed glasses, roomy African print shirt and all.

- The walls are adorned with hangings and framed pictures. Murumbi’s gown drapes a coat hanger.

For most people hurrying to work in the morning or trudging back into town in the evening, the owl-grey house at the intersection of Kenyatta and Uhuru highways in Nairobi City is merely a relic hanging onto its colonial identity. The tiny building sits in the hulking yellow shadow of Nyayo House, and with nary a lick of paint touching its exterior, it is forgettable.

Yet there is hardly another building in the Kenyan capital more memorable and timeless than the Murumbi African Heritage Collections. But that the building should repose in its understated profile is not entirely a negative thing. The identity is almost filial. You can walk the streets with a microphone and poll 10 random people and eight of the respondents would have to rush to old Google to name Kenya’s second Vice-President Joseph Murumbi, the man the museum is named for.

Murumbi, who died in 1990, was one of the more understated, if not scholarly, of all Kenyan deputies. His tenure ended in a resignation after Murumbi had been in the office a partly six months in office (May-December 1966).

In a way, the museum mirrors the wizened village octogenarian who sits in the shade, files of history secure in his memory hoping that an inquisitive pilgrim will walk through the gate with pen and paper, in search of history before Alzheimer’s or dotage erases all those files for good.

Over the course of a multi-layered and erudite life, Murumbi, together with his wife Sheila, amassed an astonishing collection of art that includes sculptures, paintings, photographs and peerless philately. The items housed in the museum are a portion of Murumbi’s full collection peopled with 50,000 books, 8,000 of them published before 1900.

Before the collection was carted to its current address, Murumbi’s collection had been housed in the Kenya National Archives after the former VP sold it to the Kenya government in the 1970s.

“There has been remarkable increase in the number of visitors,” says a curator as he chaperones visitors around the museum. I pose: What is the native/foreigner ratio? The young archivist mulls this, then smiles cautiously. “We can do better.”

This guarded response bears the undertones of our complicated and unresolved relationship with the past.

For all its monuments and trinkets of history, a large number of the city’s four million dwellers are irretrievably jaded of the history that weaves the streets and avenues and soul of the country.

Indeed, until a group welded rails and paraded pictures chronicling Kenya’s eventful past, and the country’s heroes outside the Kenya National Archives early in 2017, the halls of the Archives echoed empty despite the comparably friendly admission fee of not more than Sh100.

EXTERIOR APPEARS SCRUFFY

While the building’s exterior appears scruffy, the interior is a revelation, and full of sun. To go inside is to walk into a miniature replica of Murumbis’ Muthaiga home. The living room is a window swung open, an invitation, and one would not be considered unbalanced to imagine Joe sweeping into the room any time, horn-rimmed glasses, roomy African print shirt and all.

The walls are adorned with hangings and framed pictures. Murumbi’s gown drapes a coat hanger. Down the hall a TV screen plays a video cassette, filling the house with the story of Africa. Paintings from all over Africa fill an adjoining room. But the most compelling of the rooms is the one housing blown-up replicas of Murumbi’s stamp collection. The stamps are life unto themselves.

The staggering collection of replicas pans most of the 20th century, evoking a longing for a gone age and the quickly departing component of postal communication, and also art and history. In one, Jomo Kenyatta wears a skull cap, a wood plane in his hand; another bears the conjoined-twins of Ruanda-Urundi (when Rwanda and Burundi were a single unit).

On a balmy afternoon, several people sit outside the Murumbi gallery building awaiting the commencement of an art celebration, which is part of various themes held at the museum from time to time. Near the entrance, Ayub Ogada and his Heritage Band entertain the visitors, the sombre and haunting delivery of Ogada’s lyre wafting among the plastic seats.

Murumbi was two years old in 1913 when Rand Ovary, the colonial government architect, drew up the blueprint for the structure that would be the office for the Ministry of Native Affairs. Over the years, the building held several identities and offices, and was once known as Hatches, Matches and Dispatches, a title advised by the trifocal roles of the Ministry: registration of births, marriages and deaths.

In the context of history, perhaps no road in the city comes close to History Boulevard as Kenyatta Avenue, and to walk the length of the road is to be in history’s half-hug. Pick your departure point: You can dine in genteel company at the pelican-white (Sarova) Stanley, relive the Great War at the handsome monument commemorating Africa’s contribution during World War II, on past the charmed little colonial-themed building that is now a branch of a local bank.

The jacaranda-tree lined avenue is as good a place as any to contemplate history’s journey. Such a folksy man as Murumbi would be right at home among the trees. But mostly, you picture him rising to his feet, offering a handshake and walking a visitor to his house. Joe would probably like to talk, in that spotless English of his, about his good friend Pio Gama Pinto, or his Goan father and Maasai mother.