Two-volume book captures 50 years of independent Kenya

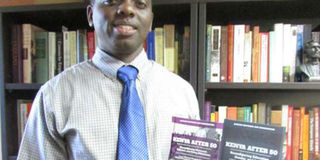

Dr Michael Mwenda-Kithinji, PhD, Interim Director, African and African American Studies Program and Assistant Professor of History, University of Central Arkansas in Conway, Arizona. He led two other US-based Kenyan scholars in editing the two-volume book 'Kenya After 50' . PHOTO| COURTESY

What you need to know:

The fact that debates on federalism lay low throughout the Jomo and Moi regimes, only to re-emerge in more vigorous tones in the 1990s, is a statement on how intolerant the two leaders were to the idea of a de-centred Kenya.

But it also means that Kenyans still wanted to move the political centre from Nairobi as it had failed to observe a sense of equity or fairness in its resource redistributive role.

Indeed, the issue of fairness in the access to national resources has always been at the centre of political contests and conflicts all over the world and we in Kenya can only deal with our own version of a global problem.

In September 2013, Kenyan scholars and students based in the US held a conference to reflect on momentous aspects of Kenya’s post-Independence history.

Held at the Bowling Green State University in Ohio, the conference brought together scholars with an orientation towards histories to reflect on definitive historic turning points in Kenya since 1963.

From the deliberations, a two-volume book has recently been published by Palgrave Macmillan under its African Histories and Modernities series. Kenya After 50: Reconfiguring Historical, Political, and Policy Milestones and Kenya After 50: Reconfiguring

Education, Gender, and Policy are edited by US-based Kenyan scholars Dr Michael Mwenda Kithinji, Dr Mickie Mwanzia-Korster and Dr Jerono Rotich.

Kenya After 50: Reconfiguring Historical, Political, and Policy Milestones brings together 10 chapters by, among others, Robert Maxon and Wanjala Nasong’o, both scholars with solid international repute.

Maxon’s chapter, ‘The Demise and Rise of Majimbo in Independent Kenya,’ sets the tone of the contributors’ engagement with some of the key themes in the volume.

Maxon demonstrates the complexities that informed the demise of the initial majimbo (Kiswahili for federalism), pointing out that a number of factors, including the government’s hostility, voter ignorance of the pro-majimbo arguments, Kadu figureheads’

doubtful dedication to the cause of majimbo, persuasive Kanu propaganda that painted pro-majimbo advocates as tribalists and opportunists who wanted to sell the country back to the colonialists and, finally, the seduction of power and material gains such as

land that pro-majimbo leaders were lured with to defect to Kanu.

The fact that debates on federalism lay low throughout the Jomo and Moi regimes, only to re-emerge in more vigorous tones in the 1990s, is a statement on how intolerant the two leaders were to the idea of a de-centred Kenya.

But it also means that Kenyans still wanted to move the political centre from Nairobi as it had failed to observe a sense of equity or fairness in its resource redistributive role.

Indeed, the issue of fairness in the access to national resources has always been at the centre of political contests and conflicts all over the world and we in Kenya can only deal with our own version of a global problem.

For us, until devolution ‘ruined’ the party, a few individuals scattered across the country determined — depending on whether they were viewed positively or otherwise by the prevailing leader — how much or little entire regions got from the centre.

In the first volume of this book, Nasong’o captures this in his chapter, ‘Kenya at Fifty and the Betrayal of Nationalism: The Paradoxes of Two Family Dynasties’, in evaluating the influence of the Oginga Odinga and Jomo Kenyatta families and later their sons

Raila Odinga and Uhuru Kenyatta in shaping the trajectory of Kenya’s post-Independence history.

In a sense, Nasong’o demonstrates the parallels between war and political contests: Both enjoy eating truth for breakfast.

The ironies and paradoxes that frame the political lives of the Kenyattas and Odingas are the stuff for a good comedy of errors, if we are to sample only one example.

When Jomo was doing time in Kapenguria as a condemned criminal, in the colonial and his kinsmen homeguard eyes, Jaramogi rehabilitated Kenyatta morally and empowered him politically by insisting that he, Jomo, was the legitimate leader of Kenyan Africans.

ALLOWED JOMO TO CATCH UP WITH HISTORY

In so doing, Odinga not only alienated himself from other Legco members from central Kenya such as Bernard Mate, Jeremiah Nyagah, Julius Gikonyo Kiano and Wanyutu Waweru — who duly issued a statement rebuking Oginga and asserting that they

were the true leaders of central Kenya — but also allowed Jomo to catch up with history and become one of the key players.

What Odinga forgot at that moment — that blood is thicker than water — Jomo remembered throughout his regime, in turn rehabilitating the likes of Kiano and collectively kicking Oginga out of the political centre.

We continue to bear the burdens of these early machinations because we are forced to tiptoe around each other as we get trapped between patriotism and tribalism, an uncharitable gift handed to us by these two so-called fathers of the nation. The first volume addresses

other important aspects of Kenya’s post-Independence history — including the ghost of Mau Mau that continues to haunt us (Mwanzia-Korster) and the other violent experience of the Shifta war (Keren Weitzberg), problems of land (Ben ole Koissaba) and trade unionism (Eric Otenyo).

The second volume traces developments in education (Mwenda-Kithinji, Margaret Njeru and Peter Ojiambo); sports (WWS Njororai) and gender dynamics (Besi Muhonja, Rotich and Kipchumba Byron).

The value of the second volume is, perhaps, in its emphasis on the idea of the ordinary as important ingredients in the making of Kenya’s history. Indeed, the tendency to focus more on political histories in our discourses on the challenges we have faced as a

country ignores other important aspects of our nationhood. The authors of the chapters in this volume should therefore be commended for the decision to include under the same title a wide spectrum of themes in Kenyan histories.

Notably, the inclusion of chapters on sports is an important highlight, coming in a country that struggles to define its nationhood through athletics and other outdoor games without a corresponding scholarship on sports’ mobilising uses in the context of

cultural and historical studies.

Rugby, football and its problems, and track athletics have all been central in the making and narration of Kenyan histories, yet little, to my knowledge, has been done by way of cultural scholarship on these areas. This book, therefore, makes a key

intervention in directing our scholarly conversations towards that direction.

Lastly, Dr Mwenda-Kithinji’s chapter, ‘Education System and University Curriculum in Kenya: Contentions, Dysfunctionality, and Reforms Since Independence’ makes for a timely and interesting read given that it comes at a time when the country is

discussing various aspects of its education system and the threats to its integrity.

Dr Mwenda-Kithinji, the lead editor of the book, is Interim Director, African and African-American Studies Program and Assistant Professor of History at the University of Central Arkansas, Conway.

Dr Siundu teaches literature at the University of Nairobi.