Why we live in a literary desert

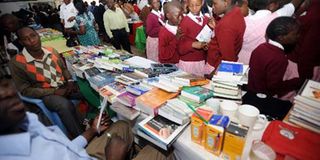

School children tour a Kenya Publishers Association regional book fair at Old Town Hall in Nakuru on June 7, 2013. The closure of Cardinal Otunga and Mangu high schools in 2001 was a result of the arrogance of government officials, who did not want to consult their sponsors, the Catholic Church. FILE PHOTO |

What you need to know:

- In my view the problem is multi-factorial and requires a multi-pronged approach. As a full-time surgeon and part-time author, I will try to outline the diagnosis and treatment.

- The tragedy is that even people who can afford it have not developed the taste for reading for pleasure. The greater tragedy is that some of us who can afford it, think nothing of spending more than a price of a novel in a bar in one evening, rather than buy a book.

- Many of them have confessed to me in private that textbooks provide them with both bread and butter and creative literature is published by them grudgingly as a means of acquiring prestige and status amongst their peers. They have to subsidise it.

Various reasons have been put forward to explain the dearth of creative writing in Kenya. Like the "Blind men of Hindustan", who described the elephant by the part of the animal’s anatomy they touched, each one of us has put forward the causes as we perceived them.

In my view the problem is multi-factorial and requires a multi-pronged approach. As a full-time surgeon and part-time author, I will try to outline the diagnosis and treatment.

The first issue that comes to mind is the reading habit of our people, or the lack of it. In the so-called developed world, I have noticed that people have an in-born habit of reading. They usually read before retiring at night, while commuting and when on holiday.

Some of them put aside some time during the day to read a book. I don’t see this trend in our part of the world. Our students have to cram so many books to obtain good grades that they vow never to read a book after passing.

NON-EDUCATIONAL

Apart from that, it could be attributed to the level of literacy, something that is being tackled by governments in our region.

The other reason could be lack of money. When majority of us live on less than a dollar and half a day, buying a book must be last on our list of priorities, if it is on the list at all.

In all fairness, until a majority of us emerge from poverty and don’t have to struggle to eke out a living, we can’t expect to indulge in the luxury of buying and reading books.

Food, shelter, education for our children and health for us all is our crying need and everything else has to be of secondary importance.

The tragedy is that even people who can afford it have not developed the taste for reading for pleasure. The greater tragedy is that some of us who can afford it, think nothing of spending more than a price of a novel in a bar in one evening, rather than buy a book.

Until the mindset of our people changes, I can’t see reading becoming a compulsive habit.

Next are the publishers, who are at the heart of the equation. Many of them have confessed to me in private that textbooks provide them with both bread and butter and creative literature is published by them grudgingly as a means of acquiring prestige and status amongst their peers. They have to subsidise it.

That explains why it receives step-motherly affection from them.

They can, however, help themselves and their authors by improving their marketing, which in turn would give them much better returns on the investment they make in publishing ‘non-educational’ books.

Regrettably, I see no marketing drive on their part, no advertising strategy, no urge or plans to place their books in supermarkets, at the airport shops and outlets other than those which only sell books as I see elsewhere.

They have to realise that even successful and fast-selling brands like Mercedes and Toyota cars, Nokia and Samsung mobile phones, Swiss and Japanese watches have to do aggressive marketing to sell their products. In fact, the Samsung advert lies on top of no less a place than KICC! Kenyan authors deserve the same treatment.

I believe that unless our publishers apply smart salesmanship in English-speaking Africa and the wider Commonwealth countries, which form an accessible and ready market for them, they have no hope of selling their books beyond a pitiful few thousand.

VALUABLE CULTURE

To their credit, I must add that the Book Fair sponsored by them and the reading habit they try to inculcate into our children by organising reading classes at the fair is highly commendable and steps in the right direction.

Next on my list are our bookshops and booksellers. I have a grudging suspicion that they suffer from chronic antipathy against local authors or they receive higher commissions, perks or better credit facilities from foreign publishers.

Only that would explain why some of them do not stock our books and those who do so, put them on the back burners, in the shelves at the back of the shop or relegate them to what they euphemistically call ‘Africana’ section.

To my chagrin, I see that we hardly ever qualify for window dressing along with Jeffrey Archer, Sydney Sheldon and Danielle Steel! To again give credit where it is due, I understand that the prestigious Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature is now sponsored by a leading bookshop in Nairobi, an award which is a great source of encouragement to our writers.

Last but not least, the government has a role to play in promoting local literature and home-grown authors. Taking the positive aspect first, provision of free primary and secondary education, espoused by them, will certainly promote literacy and the habit of reading for pleasure. But it has to do much more. It has to recognise the role of art and science in our society.

Man does not live by bread alone and a country is known by the value it attaches to its culture.

In its honours list, it is not enough for it to recognise only politicians, members of the defence forces and rich folks. Neither should it dish out all the prestigious posts to them. People of science, literature, music, arts and sports should be given their rightful share. This is the surest way to recognise their contribution to the country and encourage them.

I hope that when the long promised Heroes’ acre comes into being, the same principle will apply.

In the same vein, universities, when conferring honorary degrees, certainly those related to literature, should set aside a proportion for writers and other artists who cumulatively form the cultural core of our country and fly its flag high.

LAST WORD

Similarly those who are entrusted to set books for schools and colleges should do it on an equitable basis and give our students an opportunity to know their local authors and let our writers share the cake.

As for our press, I have a small bouquet for them because recently our two leading newspapers are dedicating a couple of pages to literature in their Saturday editions. They can do a lot more to increase the reading culture and promote our budding and established authors alike.

The last word on the subject must come from my physician colleague-cum-philosopher. Hippocrates said that every time a writer dips his pen in the inkpot, he leaves a bit of his flesh and soul behind. In my view, it is not enough to compensate him or her by paying a few thousand shillings in the form of royalties at the end of the year. Creative writing is a very lonely occupation, requiring many hours of hard labour. What eventually emerges as the printed product is a result of many revised and rewritten drafts, following many frustrations and after experiencing a few writer’s cramps and mental blocks.

No wonder there is paucity of full- time writers in Kenya. This is simply because they can’t survive solely on their writing income. Most of us do it as a labour of love!