Writers dialogue on what nationhood means for Kenyans

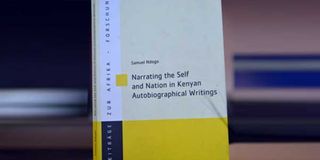

In his new book, Narrating the Self and Nation in Kenya Autobiographical Writings, Dr Samuel Ndogo takes on the laziness inherent in this academic exceptionalism by studying the nexus of autobiographical writing and the nation. PHOTO | NATION

What you need to know:

- In his new book, Narrating the Self and Nation in Kenya Autobiographical Writings, Dr Samuel Ndogo takes on the laziness inherent in this academic exceptionalism by studying the nexus of autobiographical writing and the nation.

- Ndogo carries out comparative studies of the autobiographical writings of a politician (Oginga Odinga), a writer (Ngugi wa Thiong’o), an activist (Wangari Maathai), and a historian (Bethwell Ogot). He wants to find out how these authors construct not just their own self identities, but also how they imagine the Kenyan nation.

- In Odinga’s Not Yet Uhuru, Ndogo finds a political icon whose imagined nation is a community of economic empowerment. In this imagined community, the ethnic group is a microcosm of the larger political community. Alas this nation exists only in this one man’s imagination.

Millions of people have sacrificed themselves at altar of the nation. International politics is built around the logic of sovereign nations. Even modern sporting competitions have become an arena for nations to assert themselves and trounce each other without spilling blood.

Yet this thing, the nation, exists primarily in our imagination. The nation is a story that we tell ourselves about where we and why we belong. It is a story told in political rhetoric; a waved flag; an imposing monument; or a powerful rendition of the national anthem. But despite its material manifestations, the nation remains an imagined community.

The study of nations and nationalism is characterised by an African-shaped caveat. The capacity of Africans to imagine their own national communities, akin to those in the West, has been questioned.

In literature, African writing has failed to comfortably fit into genres born in the West. Does an autobiography written by an African, preoccupied more with community than the self, count as autobiography? For some scholars the answer is a resounding “no”.

In his new book, Narrating the Self and Nation in Kenya Autobiographical Writings, Dr Samuel Ndogo takes on the laziness inherent in this academic exceptionalism by studying the nexus of autobiographical writing and the nation.

Ndogo carries out comparative studies of the autobiographical writings of a politician (Oginga Odinga), a writer (Ngugi wa Thiong’o), an activist (Wangari Maathai), and a historian (Bethwell Ogot). He wants to find out how these authors construct not just their own self identities, but also how they imagine the Kenyan nation.

RICH INTEXTUALITY

In Odinga’s Not Yet Uhuru, Ndogo finds a political icon whose imagined nation is a community of economic empowerment. In this imagined community, the ethnic group is a microcosm of the larger political community. Alas this nation exists only in this one man’s imagination. Greed and political machination have crippled the ability of the rest of the country to hold a similar vision in their minds and thus Odinga’s Kenya is stillborn.

The book tackles two of Ngugi’s autobiographical writings. In Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary, the writer, uprooted from his community, does not wilt and rather flowers as a creative. This ‘self’ of Ngugi as a creative is fleshed out more in Dreams in a Time of War where, as Ndogo argues, the writer imagines himself as a mythmaker. Ngugi’s imagination of the nation is rooted deeply in history. By writing his stories, he narrates the birth of a nation and at the same time helps construct myths on which Kenya as a nation must lay its foundation.

Ndogo chooses Maathai’s Unbowed partly to provide the ‘female’ perspective. And although I quibbled with the view that women must primarily be engaged with on the basis of their gender, I do think that perhaps this chapter is the most fascinating.

Maathai discusses the ‘self’ as it exists in both the public and private sphere. Her work as an environmental activist saw her attacked not just in at Karura Forest but in her marriage, and in her own body.

“In that sense, the two categories — the woman’s body and the natural environment — can be viewed metaphorically as spaces of resistance and violation… it is from this perspective that Maathai provides a new paradigm of imagining and narrating the nation,” writes Ndogo.

As he narrates his life in My Footprints on the Sands of Time, an epic-like tale in which he is the hero, Ogot’s idea of the Kenyan nation comes through as a community that is characterised by heterogeneity rather than homogeneity.

Although these writers and their ideas are presented discretely, Ndogo allows them to go into dialogue with each other. This rich intertextuality extends beyond the four sampled authors and into other works of literature from East Africa and beyond.

While Ndogo has managed to provide a fascinating view into his subject, I was sometimes unsatisfied with his analytical rigour, especially on the subject of nationhood.

I also found that Ndogo often blurred the line between State-building and nation-building. Ogot’s role in the foundation of Maseno University may be seen more of as part of an exercise to set up the pillars that support the State, that administrative skeleton that rests inside the nation, unless the university’s role in the nationalist project can be demonstrated. Ndogo does not do this.

The authors with whom Ndogo interacts are iconic and sometimes he lets himself get carried away by his admiration of them. In such instances, his academic text begins to sound, at best, like a normative formula for good statesmanship and, at worst, a motivational piece.

I wish to close with a caveat. Ndogo’s is an academic text. However, it should join the reading list not just for literature scholars but also for academics fascinated by nationhood in Kenya and Africa.