You’ll burn your fingers self-publishing fictive tales

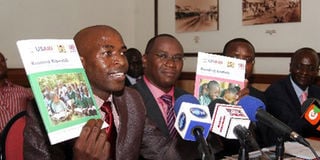

Phoenix Publishers limited chief executive officer John Mwazemba (left) and Kenya Publishers Association chairman Lawrence Njagi in a file photo. It takes a village but somehow, everyone blames publishers for a poor reading culture (Your children not reading? Whack the publishers)! PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- If, as Ng’ang’a Mbugua intimated, a writer could sell 800 copies a year, someone who has spent about Sh200,000 to print a title of a book could rue the day they were born and for such a writer, publishing is indeed, ‘short, nasty and brutish’. That is a phrase borrowed from Thomas Hobbes to denote that life in publishing fiction could be a struggle.

- My definition of a self-published author is one who may have just one title, gets copies of it from a printer, carries them home and sells them from their living room or garage. These are the authors I have met who look flabbergasted; bookshops shy away from even stocking their books and sometimes go out of pocket after using hundreds of thousands to print their books.

- An award-winning writer (out of no fault of his own), selling 800 copies of a book to 40 million Kenyans blows into smithereens all notions of us having a ‘great’ reading culture. And the story is no different in other publishing houses.

“It was a fine cry — loud and long — but it had no bottom and it had no top, just circles and circles of sorrow”.

These words, by a character in Toni Morrison’s novel, Sula, capture the unending (with no top, just circles and circles) debate on Kenya’s reading culture and, recently, self-publishing in Kenya.

Reading is a culture — meaning we all have to play our part to nurture it from publishers, parents, the government, teachers, the media to the entire society. It takes a village but somehow, everyone blames publishers for a poor reading culture (Your children not reading? Whack the publishers)!

Ng’ang’a Mbugua’s article, “Mwazemba is off the mark, self-publishing worth the gamble” (October 4, 2014), was an interesting if somewhat contradictory read.

The writer gave damning statistics — strengthening my central argument and indicting our reading culture. Yes, self-publishing is an option.

All of us dream of immortality like the character in Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial novel, Lolita, who says, “I am thinking of aurochs and angels, the secret of durable pigments, prophetic sonnets, the refuge of art. And this is the only immortality you and I may share, my Lolita”.

READY CONGREGATIONS

Sometimes we see writing as ‘our only immortality’. Ng’ang’a Mbugua wrote that one self-published writer told him, “Now, even if I die, I will die a happy man. I have published a book.” Is our immortality enough to inspire us to self-publish?

It cannot be denied that self-publishing has its benefits especially for motivation speakers, pastors, some specialists and even performing poets who have congregations or seminars they can sell books to after their presentations. However, it is never a good idea to self-publish fiction unless the writer can absolutely not find any commercial publisher, they just want a book out so they can say they ‘published a book before they died’ or they have cash to spare. I do not consider writers who started publishing houses like Ng’ang’a Mbugua with Big Books, David Maillu with Comb Books, Prof K. W Wamitila with Vide-Muwa or Kithaka wa Mberia with Marimba Publishers as self-published authors; they are bona fide publishers.

My definition of a self-published author is one who may have just one title, gets copies of it from a printer, carries them home and sells them from their living room or garage. These are the authors I have met who look flabbergasted; bookshops shy away from even stocking their books and sometimes go out of pocket after using hundreds of thousands to print their books.

After publishing a book, distribution is the most challenging part. Pastors and motivational speakers have ready ‘congregations’ but authors who self-publish fiction must work hard to distribute their books and this could be very costly and time-consuming.

Commercial publishers have created formidable networks all over the country (and still manage to do poorly in fiction sales!)

If, as Ng’ang’a Mbugua intimated, a writer could sell 800 copies a year, someone who has spent about Sh200,000 to print a title of a book could rue the day they were born and for such a writer, publishing is indeed, ‘short, nasty and brutish’. That is a phrase borrowed from Thomas Hobbes to denote that life in publishing fiction could be a struggle.

And what Ng’ang’a Mbugua didn’t mention is that 30 per cent of the cash from the 800 copies sold in a year went to bookshops as trade discount, about 25 per cent to the printer not factoring in office rent, overheads (estimated at 20 per cent). Other publishers have these costs and still have to pay writers 10 per cent royalty and use about 10 per cent on distribution and they are still called thieves by writers for their trouble! What keeps commercial publishers in business is the diverse range of products they have.

DIGITAL AGE

An alarmed Kenyan sent me a message immediately after reading Mbugua’s article. “The statistics are grim,” he sounded surprised.

Considering that Mbugua is one of our award-winning writers, and still sells only a few copies every year of a single title (sometimes less than 1000 copies)!

An award-winning writer (out of no fault of his own), selling 800 copies of a book to 40 million Kenyans blows into smithereens all notions of us having a ‘great’ reading culture. And the story is no different in other publishing houses.

Ng’ang’a Mbugua was right in noting that the digital age has made it easier for writers to self-publish if they so wish.

However, the digital age has also birthed many poorly-edited works and many others with terrible content. We are almost living Oscar Wilde’s words, “In old days books were written by men of letters and read by the public. Nowadays books are written by the public and read by nobody.” My advice is for writers to self-publish fiction as an absolute last resort.