From ‘nyatiti’ to iPod: retracing the benga rhythm

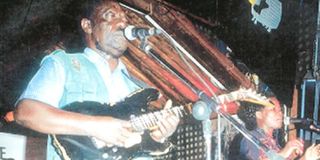

Benga musician DO Misiani (left), who has since died, whose music is said to have reached Zimbabwe and may have influenced artistes like Oliver Mtukudzi.

If you were to take a cross-country bus ride and doze off midway through the journey, you would know that you had reached the sprawling Kisumu if you were jerked awake by the sound of pulsating guitar music.

As the sun sets, the fast-paced, invigorating music migrates from the bus park to the strobe-lit dance-floors of the many clubs in the part of town called Kondele that have names like Donna and Bottoms Up. Live benga music is the one reason why club business is still big business in the lakeside town, attracting patrons, including Members of Parliament.

And it is not just in Kisumu where you can hear benga. In other major towns in Nyanza and Western provinces one is bound to encounter varieties of the musical form.

You will hear it blaring from a barbershop in Kisii, a portable radio on a boda boda (bicycle taxi) in Kakamega, and an eatery in Kericho. Across the region the basic beat is the same: three or four electric guitars stringing complex rhythms over a thumping backbeat. Only the lyrics and pace change.

It is this unique musical heritage and its effect on the region’s lifestyle that inspired Retracing the Benga Rhythm, a narrative in prose, music and video that explores the background of benga.

The narrative links the benga sound to the nyatiti, a traditional Luo instrument eight-string wooden-framed lyre with a resonator made from a gourd.

The rhythmic thumping of an iron bangle on the toe of the player as it hits the frame is considered the most crucial link between the instrument and the distinct style of Luo benga guitarists.

Unlike the Congolese, who massage their guitar strings, Luo instrumentalists rapidly pluck and pick single notes as though they were playing a nyatiti.

Benga’s origins are unclear. Some link it to the Luo word, obengore, which implies a state of looseness and which aptly captures the mood on the dance floor at a benga show where the revellers let down their hair and dance with abandon.

Others link the word to a loose skirt of the same name that was at one time fashionable in the region and which originated from Uganda. Whatever its origins, the genre has a distinct identity that might some day define authentic East African music.

Riding on a sharp lead guitar that generally overrides the rhythm and bass, benga is distinct in that unlike other genres like rhumba, partners generally do not hold hands; each is free to find his or her own space on the dance floor. The lyrics are generally based on the love theme, further indicating that it is a style intended to make people feel good.

If there were a benga Hall of Fame, John Ogara Odondi ‘Kaisa’ would take pride of place. Veteran Kericho-based producer A.P. Chandarana simply stated: “Benga is Ogara.” His success was likely due to the fact that he managed to take the music beyond Luo Nyanza to Nairobi, Central Province and Ukambani.

Chandarana and other producers helped benga get a footing. It is said that Mzee Daudia, the owner of Melodica, which still stands today on Tom Mboya Street, had a set of dentures that he would make the Luo vocalists wear before a recording to reduce the hissing sound caused by the gap where their six lower teeth had been removed.

According to the narrative, DO Misiani’s benga music reached Zimbabwe at one point and may have influenced artistes like Oliver Mtukudzi, The Bhundu Boys and the jazz act, African Guitar Kings.

Benga’s influence reached as far as Ghana and Cameroon. As if to give credence to the strong link between benga and the music of Central Africa, it is said that at one time Congolese greats like Franco, Verkys Kiamuamgana, Mbilia Bel and Tabu Ley visited the home of ace producer and one-time Rongo MP Phares Oluoch Kanindo in Awendo, South Nyanza.

Congolese sound

That might explain why during the late 1970s and 1980s when Congolese musicians pitched camp in Kenya they had a large following in Kisumu and the Western region. Obviously the fans could identify something familiar in the Congolese sound.

For some reason, benga has not been taken very seriously by mainstream music promoters who consider it music for rural folk, or shagzmondos, as the hip urbanites would say.

This is the reason why benga shows that come to Nairobi are staged in places like Huruma, Kariobangi, Kibera and Kawangware where the musicians are comfortable with the public.

The fact that benga artistes have been slow to embrace modern technology makes it difficult to sell the style to the Ipod generation.

They might want to take a leaf from the book of the versatile Congolese who at one time almost overshadowed them in their own turf. In addition to well-organised management and immense financial backing, the tech-savvy Congolese are adept at changing with the times.

Smaller groups

However, like flies to an old dog, it seems that both the benga and Congolese musicians face similar problems. Apparently successful Congolese bands splintered into other bands like Wenga Musica from Zaiko Langa Langa. The same happened on the benga scene with bands like Victoria Kings and Shirati Jazz splitting off into various smaller groups.

TPOK Jazz’s Franco supported Mobutu Sese Seko’s 1970 election campaign with his music and thereafter helped the Congolese leader to popularize his doctrine of authenticity.

But Franco would later fall out of favour with the authorities with the release of songs like Quatre Boutons and Mobali na Ngai that were considered scandalous, and which were banned.

DO Misiani dallied with Kenyan politicians, falling into their favour whenever he released songs that caressed the heart. But he would have to flee for safety to his native Shirati in Tanzania whenever he castigated the same politicians in his songs.

The jukebox came and went, and the cassette is floundering on its deathbed. But it seems that benga has yet to breathe its last. With today’s Afro-fusion artistes like Eric Wainaina and Suzanna Owiyo still drawing inspiration from the genre, it may be that the old-time crooners like Ogara and Misiani are whistling in their graves.

Retracing the Benga Rythm is a beautifully-woven package that should be on the shelf of every music lover. It includes a 13-track audio CD, a DVD documentary and a booklet.

It was compiled and edited by Ketebul Music Studio’s Tabu Osusa, Paul “Maddo” Kelemba and Njeri Muhoro. John Sibi-Okumu does the narration. The whole project was supported by The Ford Foundation.