Where residents would prefer jail to plundering their forest

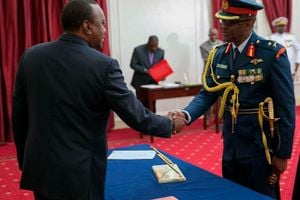

Senior deputy director of the Kenya Forest Service, Emilio Mugo admires a sandalwood tree growing in Mukogodo forest. The tree is in demand on the black market where it is exported to South Asian countries. Photos/MWANGI NDIRANGU

It is a forest like no other. And for its uniqueness, it is being used as a case study in conservation efforts, not only in Kenya but in other East African nations.

Mukogodo in Laikipia North District is the only forest in Kenya with no guards, yet it has resources worth millions of shillings and is home to more than 4,000 people.

Driving around the 74,000-acre forest, one comes across wildlife and livestock grazing side by side and dozens of temporary and permanent shelters.

Piles of rotting logs that would make a charcoal trader drool with envy are scattered all over the place but the locals dare not touch them lest they incur the wrath of the elders’ court.

A senior deputy director with the Kenya Forest Service (KFS), Mr Emilio Mugo, said despite spending a fortune hiring guards for other forests in the country, illegal logging was still a major headache.

But not in Mukogodo, where cases of illegal logging or charcoal burning are rare despite the area having one guard whose main preoccupation is to coordinate rescue efforts in case of natural disasters.

“This forest is unique and whenever we go to Uganda or Ethiopia for international conservation conferences, we use it as case study and urge people to visit,” he said recently during a trip to the forest to launch a 10-year integrated management plan.

The plan is targeted at nine districts in line with the new Forest Act, which now gives the community a bigger role in conservation efforts.

However, even before the new Act became law last year, residents of Mukogodo had their own traditional methods of conserving the forest, which has been their means of livelihood for centuries.

How has the community been so successful in conserving the forest?

Historians say the Maasais were pushed into the Dorobo Reserve (now Mukogodo) in 1936 by colonialists who settled in the Laikipia plateau.

Poor people

In the forest the Maasai, who are pastoralists, had to develop suitable economic and political structures to survive.

They had to ensure that every locality had a dry season grazing area with perennial water supply as well as wet season pastures.

Livestock could not be driven to the zoned areas unless a committee of elders gave the nod.

The forest was also a source of firewood, herbs, honey and natural dyes.

It also has a cultural significance as has various sites and tree species which are used to conduct thanksgiving, circumcision and other ceremonies.

Before the Maasais moved into the forest, it was the home to the Yiaku, a Cushitic community that has, over the years, been assimilated into the Maasai culture.

The Yiaku, believed to have settled in the forest about 4,000 years ago, were derogatorily referred to by the Maasai as Iltorobo — poor people with no cattle.

The community, whose language has been classified as extinct by Unesco, has for centuries depended on Mukogodo forest for survival and jealously guarded the area.

When the Maasai settled there, they continued the tradition as the forest supported their pastoral way of life.

Mr Mugo assured the community that the new management plan did not mean that they would be evicted like other groups who have occupied forests.

“All squatters occupying Government forest have to move out. But here, the situation is different and you will not be evicted. The only change is that you will now work with Government agencies in your conservation efforts,” said Mr Mugo.

He admitted that the KFS was in a dilemma on how to remove squatters who invaded forests years ago. “We have been to Eburu in Mau and Rumuruti forests and told the people who have turned these resources into settlements that it was time to move out,” he said.

Mukogodo forest officer Simon Gioche said there are more than 200 species of indigenous trees in the forest.

He said sandalwood, which fetches Sh400 a kilogramme on the black market, is abundant.

“The locals are aware that sandalwood is highly sought on the black market but that does not excite them and they only take its bark to make herbal tea,” he said.

Thousands of cedar trees, coveted for their high quality fencing posts, are of little interest to the forest inhabitants, said Mr Gioche.

Sitting on goldmine

Though they are sitting on a goldmine, the pastoralists leave one in no doubt that they have for a long time known the dangers of destroying natural resources, even before renowned environmentalist Prof Wangari Maathai made her famous statement that “nature is very unforgiving”.

“We are currently experiencing hunger but we would rather steal livestock from neighbourings and risk going to jail than exploit our source of livelihood,” said Mr Paul Shuela, a civic leader.

Deep inside the forest, are two major rivers and four springs, which are a source of water for livestock and wild animals.

Built lodges

“We have learnt to co-exist with wildlife and trees because they support our lives,” said Mzee George Rambei, a community elder.

The elder said the community has rules and those who break them by either grazing or collecting firewood in prohibited areas are penalised by an elders’ court.

Mzee Rambei is the chairman of four community group ranches, Il Ngwesi, Makurian, Kurikuri and Lekuruki, that provide pasture. The community is also involved in eco-tourism projects and has two lodges on the ranches for tourists.

Mr Gioche said Mukogodo forest has a rich biodiversity in terms of fauna and flora with a recent inventory indicating that it is home to 209 bird species, 11 small mammals and 34 large mammals. More than 100 species of butterflies are also found here.

Women also make beads and other artefacts to sell to tourists.

Money raised through tourism is used to build schools in the forest.